Allied logistics in the Kokoda Track campaign facts for kids

During World War II, getting supplies and support to soldiers in Papua New Guinea was super important for winning the Kokoda Track campaign. As General Douglas MacArthur said, the biggest challenge in the Pacific War was moving troops and keeping them supplied. Winning depended on solving these supply problems.

Port Moresby, the main town in Papua, was a key location. But in early 1942, it only had two airfields and basic port facilities. A huge amount of work was needed to turn it into a major base for air and land operations against the Japanese. This was tough because Japanese planes often attacked. During the Kokoda Track campaign, the two original airfields were made better, and five new ones were built. Engineers had to build runways, paths for planes (taxiways), parking spots (hardstands), and roads.

The port was also very important, but it was small. To make it bigger, a causeway (a raised road over water) was built to Tatana Island. Here, floating docks were set up. Engineers also built roads, storage buildings, and a water treatment plant. They managed the town's electricity and water and even dug up stone for roads and airfields.

The land inside Papua was covered in thick rainforest and tall mountains. Wheeled vehicles couldn't get through. The Australian Army had to use air transport and local Papuan carriers, which were new ways of moving things for them. Air supply methods were very new. There weren't many planes, and they were all different types, making maintenance hard. Flying in New Guinea was also difficult because of the weather. Transport planes could be attacked in the air and destroyed on the ground by Japanese raids.

When the airstrip at Kokoda was lost, supplies had to be dropped from planes. There weren't enough parachutes, so supplies were often dropped without them. Many items broke or were lost, which was a big problem.

Thousands of Papuans were asked to help with the war effort. Trucks and jeeps could only carry supplies part of the way. Pack animals and a cable car took them a bit farther. The rest of the journey was done by Papuan carriers, who carried heavy loads over the mountains. The environment was dangerous due to common tropical illnesses like dysentery, scrub typhus, and malaria. Medical teams had to fight these diseases while also caring for sick and wounded soldiers. Many wounded had to walk back to the base along the Kokoda Track. Often, Papuan carriers helped carry the wounded back, earning them the nickname "Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels".

Contents

Understanding the Area

Land and Climate

In 1942, Papua was part of Australia. It covered the southeastern part of the island of New Guinea, about 91,000 square miles. Most of the land was rainforest, and higher areas were covered in moss. The climate was usually hot and humid with lots of rain, though higher parts were cold, especially at night. Tropical illnesses like malaria, scrub typhus, and dysentery were common. The local people also suffered from skin ulcers, yaws, and diseases caused by not enough vitamins.

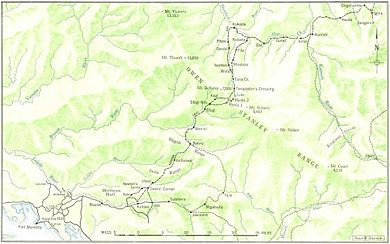

About 300,000 people lived there, with only 1,800 Europeans. There were very few Asians because of Australia's immigration rules. Not much development had happened, and there wasn't much infrastructure, except around Port Moresby on the southern coast. Port Moresby had two airfields and basic port facilities. It was relatively dry, with less than 40 inches of rain a year. By air, it was 620 nautical miles from the nearest Allied airbase in Townsville, Australia. However, Japanese airfields at Lae and Salamaua were less than 200 nautical miles away.

The Kokoda Track is a walking path that goes about 96 kilometers overland from Kokoda through the Owen Stanley Range towards Port Moresby. It was used as a mail route before the war. While there's a main track where most of the fighting happened, many other paths run alongside it. The track reaches a height of 15,400 feet. The land goes up and down a lot, sometimes by as much as 5,000 meters. This makes the journey much longer. Some flat areas exist, especially around Myola. Higher parts of the track are often above the clouds, leading to fog.

War Plans

In the first six months of the Pacific War, Japanese forces quickly took over many areas. Rabaul was captured in January 1942, Singapore in February, and Lae and Salamaua in March. American and Australian military leaders worried that the Japanese would try to cut off Australia's connection with the United States by attacking Port Moresby.

In April, Allied intelligence warned of a Japanese sea attack on Port Moresby. This attack was stopped in the Battle of the Coral Sea in May. General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of the Allied forces in the South West Pacific, arrived in Australia in March. By June, he was told that the Japanese might try to attack Port Moresby overland from Buna through Kokoda.

On June 20, General Sir Thomas Blamey ordered Brigadier Basil Morris, who was in charge of troops in Papua and New Guinea, to stop this attack. After the Battle of Midway in June, MacArthur started planning to take back Rabaul. A first step was to secure the Buna area, where airfields could be built to attack Japanese bases without flying over the Owen Stanley Range.

Setting Up the Base

Port Facilities

In early 1942, Port Moresby had only one large wharf and two small jetties. The main wharf was long and wide enough for only one large cargo ship at a time. The smaller jetties could only be used by smaller boats.

To unload ships faster, a special unit that had worked in the siege of Tobruk was sent to Port Moresby. They arrived on August 23 and found only two small boats and no tugboats. They fixed the wharf's crane and used parts from a sunken ship to help. More harbor boats arrived later, but there was never more than one tugboat and ten small boats available in 1942. Unloading was still slow because there wasn't much storage space near the wharf. Supplies were stored in the hills up to 25 miles away, the roads were bad, and there weren't enough trucks to move things.

On October 12, eight ships waiting to unload at Port Moresby were sitting idle off Townsville or Cairns. It would take two weeks to unload them at the current speed. Five of these ships were carrying equipment needed to improve the port! Extending the main wharf needed special wood and poles that weren't available right away.

So, a bold plan was made. Tatana Island, about 3 miles west of Port Moresby, had deep water nearby. It was separated from the mainland by shallow water and a coral reef. The idea was to build a causeway from the mainland to Tatana Island, where floating docks could be built. The materials were available immediately.

Work started on October 5. Equipment and people were sent to Tatana Island so they could build from both ends. About 50,000 cubic yards of dirt and rock were needed to build a road 2,250 feet long and 24 feet wide, 2 feet above high tide. The causeway was finished on October 30, and the first ship docked there on November 3. This increased the port's capacity from 1,400 to 4,000 tons per day!

However, there were problems. Heavy rain on October 21 flooded the airfields. The commander of Allied Air Forces, General George C. Kenney, warned that planes might not be able to operate without proper taxiways and roads. More engineers were sent to Port Moresby, and Australians took over work on the port and a stone quarry.

Airfields

In March 1942, General MacArthur sent his engineers to Port Moresby to plan how to develop it into a major base. They realized that to protect the area, they needed to improve airfields in other places too, like Horn Island and on the Cape York Peninsula in Australia. This would help protect ships crossing the Torres Strait. To protect Port Moresby's eastern side, an airstrip was built at Milne Bay. Another strip was built at Merauke to protect the western side.

The airfields in Port Moresby were first named by their distance from the town. In April 1942, only two were ready: Seven Mile Drome (built by the RAAF) and Three Mile Drome (a pre-war civilian airfield). Work had started on two more: Fourteen Mile and Five Mile. Four more were later built: Twelve Mile, Seventeen Mile, and Thirty Mile.

On November 10, the Port Moresby airfields (except Kila) were renamed after brave men who had died defending them. Seven Mile became Jackson, Fourteen Mile became Schwimmer, and Five Mile became Ward. Twelve Mile was renamed Berry, and Seventeen Mile became Durand. Thirty Mile Drome was renamed Rogers.

Engineers learned a lot about building airfields in Papua, especially how important good drainage was. The main airfield, Jackson, had too much tar on its runway, which became soft in the heat. When it was removed, water seeped up from the ground. Engineers had to install underground drains and lay a new 10-inch base of crushed rock.

Kila Drome was thought to be only for emergencies because a high ridge nearby made flying difficult. However, it was rarely foggy and could often be used when other airfields were closed. So, it was decided to make its runway bigger. The first layer of tar was put down in November 1942, but heavy rains came before the final layer, making the runway very muddy and dangerous. Engineers dug a ditch along the runway, but this was also dangerous for planes. They then filled the ditch with rock to create a "French drain" (a trench filled with gravel to drain water).

Schwimmer Drome was carved out of the jungle by bulldozers. It was close to the Laloki River and often flooded. The runway was built on sand and gravel, and a special metal mat (Marston Mat) was used for the surface. This runway wasn't good in all weather, so a second runway was built next to it using gravel from the Laloki River. This new runway, also 5,000 by 100 feet, was ready in November 1942. A low bridge over the Laloki River provided access, but it was known that floods might wash it away. This happened on October 21, and the bridge was later replaced with a strong steel structure.

To allow heavy four-engine bombers to fly long missions, longer, all-weather airfields were needed. Wards and Seventeen Mile were chosen for this. At Wards, a new 6,000 by 100-foot runway was built with a 12-inch thick gravel surface to support heavy bombers. At Seventeen Mile, the area was cleared, and a 6,000 by 100-foot runway was built. It was surfaced with clay-bound shale and sealed with tar, but this didn't work well, so Marston Mat had to be laid down.

Thirty Mile Drome was located on Galley Reach, an inlet about 30 miles northwest of Port Moresby, accessible by water. A dry-weather airstrip was built there with the help of many Papuan laborers. This was ready by July 20, but building it into an airbase needed two docks. Work was stopped in September due to Japanese patrols nearby. By the end of November, the runway was extended to 6,000 by 100 feet. Work continued on all other airfields in 1943, but Rogers Drome was eventually abandoned.

Base Facilities

A special company was in charge of Port Moresby's power, freezers, electricity, lighting, and water supply. By June 1942, the water supply was almost at its limit. The main water pipe ran under Jackson Drome, a frequent target for Japanese air raids, so it often broke. There were 40 to 50 breaks each month. By October 1942, the water level in the reservoir was falling. A new water intake and pumping station were built to bring water from the Laloki River to a treatment plant.

Supply depots were built inland, away from the port, because the Japanese threatened to land on the coast. A 20 mph speed limit was set on the main road to prevent damage. This road was very dusty when dry and muddy when wet. It quickly broke down under heavy military traffic. The road was only wide enough for one-way traffic and had sharp turns.

The depots and airbases needed good roads, so engineers made this a high priority. They worked hard to make roads usable in all weather before the wet season. New roads were also built, like the By Pass Road, which helped divert traffic from the main road near Jackson Drome. This road was later extended to other airfields. The opening of the new wharf at Tatana Island in October caused a sudden increase in road traffic, so a new Barune Road was opened in November. Luckily, the local red shale, when mixed with clay and rock, became hard like concrete when wet. This could handle vehicle traffic, though it was dusty when dry and slippery when wet. Stone for roads came from the Nine Mile Quarry.

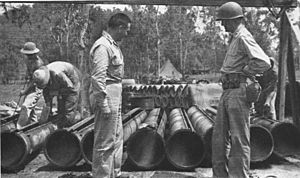

Fuel was shipped in large 44-gallon drums because there were no bulk storage facilities. A shortage of these drums developed in late 1942. New drums were ordered from Australia, and people were asked to return empty ones. A big effort to collect empty drums in Port Moresby resulted in over 20,000 being sent back to Australia in November.

The Nine Mile Quarry was crucial for road and airfield development. It was worked 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Stone was drilled and blasted from the quarry face, then broken into smaller pieces by hand. Two rock crushers were used to process the stone.

Supporting the Soldiers

Moving Supplies Overland

When the campaign started, the Kokoda Track began at McDonald's Corner, near Ilolo. From there, the track slowly climbed about 2,200 feet to what became known as Owers' Corner. The road from Port Moresby was paved up to Seven Mile, and then a gravel road was laid to Sogeri, about 32 miles from Port Moresby. On June 24, military leaders wondered if the track could be improved for animals or even vehicles.

In July, New Guinea Force had 1,140 motor vehicles, but many were in poor condition and needed spare parts. More vehicles arrived with the 7th Division, and a workshop was set up at Ilolo to service engineer equipment.

Owers' Corner was named after Lieutenant Noel Owers, who surveyed a new route from Ilolo to Nauro. The project to build a jeep track to Nauro was strongly supported. Work began on August 19. By removing trees and adding drainage, a track was created that light vehicles could use. Owers' Corner was reached in early September.

At this point, the jeep track was abandoned because the route was too steep for vehicles. Work continued on a mule track, which advanced about 2 miles a day until mid-September. Engineers were then pulled back to Port Moresby because the Japanese were getting close to Ioribaiwa. Work resumed on September 28 but was abandoned in early October. Improvements to the road allowed 3-ton trucks to reach Owers' Corner on September 28.

A small unit with horses and mules was formed to carry supplies on the Kokoda Track. They used horses and mules from local plantations. Mules were found to be the best for the job. Each animal carried 160 pounds of supplies, packed in bags so they could be easily transferred to Papuan carriers. The Goldie River was bridged on July 2, and the mule track was extended to Uberi.

A cable car was built near Owers' Corner to help move supplies down a steep descent to the Goldie River. It started operating on September 26. It was 1,200 feet long and could carry up to 300 pounds.

The 1st Pack Transport Company, with mules and horses, arrived in Port Moresby in October and began taking over from the Light Horse Troop. In total, about 1,418,310 pounds of supplies were moved forward by animal transport.

Supplies were brought from depots to Newton's Depot by 3-ton trucks, then by jeep to Owers' Corner. The cable car took them to the Goldie River Valley, and from there, Papuan porters carried them. If there were more supplies than animals could carry, the porters helped with that too.

Since the number of pack animals and carriers was limited, all supply requests were sent to headquarters, which decided what was most important to move. As Australians advanced towards Kokoda in October, the supply line became longer, and the need for carriers grew.

From Uberi, the track went to Ioribaiwa. The first 3 miles involved a very tough 1,200-foot climb. Engineers cut steps into the path, creating what became known as the "Golden Stairs." This made it harder for walkers, especially the Papuans, who were not used to stairs.

Papuan carriers moved supplies forward from Uberi, often in very difficult conditions. On June 15, 1942, an order was issued to recruit Papuan labor to support the Australian war effort. About 800 Papuan civilians were working in the Port Moresby area in April 1942. By October 9, over 9,000 Papuan workers were helping. Taking so many men away caused hardship for their families and villages, as food production dropped. However, Japanese cruelty towards Papuan civilians encouraged many to join the Allied effort.

A carrier could carry about 40 pounds, but the wet wrapping often made it heavier. The initial movement of the 39th Infantry Battalion to Kokoda was supported by 600 carriers. Along the track, way stations were set up and stocked with local food.

The Allied retreat from Kokoda in August and September was very hard for the carriers. They were pushed to their limits, hauling supplies to the front and then carrying the wounded back. It took eight men to move each wounded soldier, and they were much slower. By August 30, almost all carriers were evacuating the wounded. The retreat and the sight of the wounded lowered the carriers' spirits.

On September 13, there were 310 carriers in the forward area and 860 at Uberi. Overwork and illness took a toll on them. Captain Geoffrey Vernon, a medical officer for the carriers, was very concerned by what he saw in August. He noted that carriers were overworked, overloaded, exposed to cold, and underfed. They often lay exhausted on the ground after dropping their loads, with only rice for a meal and not enough blankets.

Newspaper reports and photos of Papuan carriers helping Australian wounded in the mountains led to a huge outpouring of thanks from Australians, who called them "Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels." This greatly changed how Australians viewed their neighbors for many years.

Air Supply

The first air transport unit in the South West Pacific was formed in Australia in January 1942. It had five C-53 planes and other aircraft. The unit was later renamed the 21st Transport Squadron. Another squadron, the 22nd Transport Squadron, was formed with planes from the Dutch East Indies. The 21st Transport Squadron flew its first mission in New Guinea on May 22, carrying supplies to Wau and Bulolo. The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) also formed transport squadrons, and No. 33 Squadron RAAF began regular flights to Port Moresby in March.

Operating in New Guinea was difficult. Bad weather often prevented flights. On May 26, five transport planes flying to Wau were attacked by Japanese Zero fighters. The transports delivered their loads, but one fighter was lost. Planes always took off in daylight because weather reports weren't available earlier, and fighter escorts couldn't fly in the dark. Weather was a constant danger over the Owen Stanley Range.

Weather and rough airstrips meant planes needed a lot of maintenance. High humidity caused electrical problems, metal rusted, and oils evaporated. Critical spare parts were often missing. A C-53 plane could carry about 5,000 pounds of supplies.

The first air transport mission to the Kokoda front was on July 26, when a DC-3 landed 15 soldiers and some supplies. The flight to Kokoda took about twenty minutes. The next day, planes found the airstrip blocked. The loss of the airstrip meant switching to air dropping supplies. On July 28, three planes dropped supplies near Kokoda.

Methods for air dropping were still new. Because of the parachute shortage, most supplies had to be "free-dropped" (dropped without parachutes), so many items broke. To prevent contents from scattering, items were put in two or more sacks. Three layers were found to be necessary. Items like blankets were preferred for packaging because they were also useful to the troops. About 12,000 blankets were used for packaging in five weeks. Without good organization, less than half of what was dropped was recovered, and only about 70 percent of that was usable.

On August 16, the air commander promised to deliver 15,000 pounds of supplies daily to the soldiers in the Kokoda area. But the next day, a disastrous Japanese air raid on Jackson Drome destroyed four bombers and three transport planes. Eight more aircraft were badly damaged.

General Rowell asked for more planes. He wanted to build up a 20-day supply of food and ammunition. General MacArthur helped by arranging for more planes. He reminded Rowell that air supply was for emergencies, not normal supply, and that other ways of supplying troops should be developed. More transport planes were sent to the South West Pacific, and new squadrons arrived in Port Moresby in October.

When the August 17 raid happened, two battalions of the 21st Infantry Brigade were moving to retake Kokoda. When they found only 10,000 rations at Myola instead of 40,000, Rowell took steps to fix the supply problem. He held back one battalion and ordered another to return to Port Moresby. Myola was lost on September 5, along with 10,000 rations. The lack of supplies at Myola made it impossible for the soldiers to fight effectively.

From September 16, supply levels were reported daily. Requests for supplies were matched with available aircraft. Trucks took supplies from depots to the airfields, where they were packaged for dropping. Standard load lists were developed. Packages of rations were "balanced" so they contained a complete set of items, meaning the loss of some packages wouldn't cause shortages of certain foods. In August, 180,779 pounds of supplies were sent by air, 306,576 pounds in September, and 1,511,726 pounds in October. New drop zones were set up around Efogi, Nauro, and Manari. Myola was recaptured on October 14 and used as a drop zone.

Medical Support

The first medical unit arrived in Port Moresby in January 1942. The main hospital became the 46th Camp Hospital. A convalescent home became the 113th Convalescent Depot. In June, the hospital ship Wanganella brought more medical units.

The 2/9th General Hospital arrived in August and moved to Rouna, 17 miles from Port Moresby. It was the only general hospital in New Guinea until January 1943. It was planned for 600 beds but held 732 patients by October 6. Its commander suggested expanding it to 1,200 beds.

Malaria was a big concern because it was common in New Guinea. There wasn't a perfect cure, and the main medicine, quinine, wasn't fully effective. Quinine was also in short supply because Java, where 90 percent of the world's supply came from, was taken by the Japanese. Many soldiers also didn't take their medicine regularly, didn't use insect repellent, or didn't wear protective clothing.

An epidemic of dysentery broke out on the Kokoda Track, threatening the entire force. About 1,200 sick soldiers, mostly with dysentery, reached Ilolo in September. Simple hygiene was needed but often ignored. A new medicine, sulphaguanidine, was shipped from Australia. Using this scarce medicine was a risk, but it worked! It stopped the epidemic and allowed sick men to travel, saving lives. When Australians advanced on Kokoda in October, special teams built latrines, buried the dead, and even burned villages that the Japanese had made very dirty.

Scrub typhus was another dangerous disease, spread by mites in the soil. It was less common than malaria or dysentery but more deadly. Skin irritation from mite bites was common but less serious. Fungal infections were also a problem because soldiers couldn't keep their clothes or boots dry. A shortage of fresh fruit and vegetables caused vitamin deficiencies. To save weight, the soldiers' rations were cut down to just six items: bully beef, biscuits, tea, sugar, salt, and dried fruit. This meant both soldiers and carriers started suffering from vitamin deficiencies, exhaustion, and illness.

Initially, wounded soldiers were evacuated forward, hoping they could be flown out from Kokoda airstrip. Where carriers couldn't go, men from the Papuan Infantry Battalion helped carry stretchers. During the retreat, wounded had to be carried along the track. Medical care was available at each way station. Only those near death were left behind. It took eight or ten Papuan carriers to move each man. Army stretchers fell apart, so Papuans made improvised stretchers from blankets, bags, and wood. The speed of the retreat depended on how fast the wounded could be moved.

When Myola was recaptured in October, a main medical station was set up there. It was hoped that planes could land at Myola to evacuate the sick and wounded. However, Myola was 6,500 feet above sea level, and pilots reported that fully loaded planes couldn't take off or land safely at that height. Five light aircraft were made available, and they evacuated some patients. But two planes crashed while trying to land at Myola in November. Over time, more than 200 patients recovered enough to return to their units. Those who could walk were sent down the track, while those who couldn't were carried to Kokoda by Papuan carriers and flown out from there.

What Was Learned

The Australian Army started World War II with limited resources because of budget cuts in the 1920s and 1930s. There was also a lack of interest in logistics from leaders. It was assumed that the Australian Army would always be part of a larger British force. This was true in earlier wars, but not in the South West Pacific, where Australia had to provide its own support and even help its Allies.

In a place where vehicles couldn't operate, the Australian Army had to rely on air transport and local carriers, which they had never used before. The Australian Army had many lessons to learn, but they were able to adapt to the tough conditions. The fighting along the Kokoda Track was just the beginning of the effort to push the Japanese out of New Guinea, which continued into 1943.

As historian John Coates wrote, the New Guinea campaign was fought with very few supplies. The isolated location, difficult land, tiring and disease-ridden climate, and lack of infrastructure made supplying military forces a constant challenge. After some early struggles, the Allies generally overcame their supply problems, but the Japanese did not. This was the most important factor in the campaign's outcome.

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |