Almack's facts for kids

Almack's was the name for several famous places and social clubs in London from the 1700s to the 1900s. Two of these clubs, Brooks's and Boodle's, became very well-known. The most famous Almack's was a building called the Almack's Assembly Rooms (later known as Willis's Rooms) on King Street, St James's. It was one of the few places where upper-class men and women could socialize together in public during London's busy social season. Even though it was famous for the club, the rooms also hosted many other events.

Contents

Who Was William Almack?

The story of Almack's begins with its founder, William Almack. Some people thought he was Scottish and had changed his name, but he was actually from Yorkshire, England. His wife, Elizabeth Cullen, was Scottish, and they might have met while working for the Duke and Duchess of Hamilton.

From 1754 to 1759, William Almack ran a coffee house. In 1759, he opened a tavern at No. 49 Pall Mall. This tavern was known for its dinners. A famous writer, Horace Walpole, once mentioned Almack's in a letter, showing it was already a popular spot for meals.

Almack's First Clubs: Brooks's and Boodle's

In January 1762, William Almack started a private club next to his tavern. This was the first of Almack's clubs and led to the creation of two major London clubs: Brooks's and Boodle's. This new club was formed to compete with another popular club called White's. One of its rules even said that members of Almack's could not also be members of White's.

Almack kept a special book with the club's rules. The first rule, from January 1, 1762, stated that Almack had rented a large new house for the club. Anyone could join until February 10, 1762. After that, new members had to be voted in, and just one "no" vote (a "black ball") could stop someone from joining. The club aimed to have no more than 250 members. Members paid two guineas each year to Almack for the house.

The club provided newspapers, dinner, and supper. Members could ask for specific dishes, but prices were set. Friends of members could visit a special room for tea or coffee, but they couldn't have meat or wine there. Gambling was allowed, but with limits. In 1762, 88 gentlemen joined the club.

In March 1764, this club either split into two or changed its structure. This might have been due to political differences or some members wanting to gamble more. Almack stopped renewing his tavern license, and his place became a private club.

One of these new groups became Brooks's. Until 1778, it met in Almack's old tavern (No. 49 Pall Mall). William Almack was still the owner, and members paid their fees to him. This club was known for heavy gambling. For example, Charles James Fox lost a lot of money there. Even Edward Gibbon, a famous historian, enjoyed the club, finding it a pleasant place to socialize.

In 1778, Brooks's moved to a new building on St. James's Street. After this, Almack's club in Pall Mall faded away. The new club is still known as Brooks's today.

The house in Pall Mall (No. 49) that Brooks's left was later used by other businesses, including a hotel and the Travellers Club. It was eventually torn down in 1894.

Next door, at No. 50 Pall Mall, was the start of another famous club, Boodle's. Edward Boodle worked with William Almack, and he took over the management of this society around 1764. Boodle's rules were very similar to Almack's original club rules. Edward Gibbon also became a member of Boodle's and even helped manage it in 1770.

Edward Boodle passed away in 1772, but the club continued to be known as Boodle's. It moved from No. 50 Pall Mall in 1783, and that building was later demolished.

The Ladies' Club or Female Coterie

From 1769 to 1771, Almack's also hosted a club for both men and women, called The Female Coterie. This club quickly became very popular. Horace Walpole described it as a new and important social group.

The main rule was that both ladies and gentlemen had to vote for new members. This meant that a lady couldn't stop another lady from joining, and a gentleman couldn't stop another gentleman. The yearly fee was five guineas. Dinner was served at 4:30 PM, and supper at 11 PM. After supper, members played cards.

By September 1770, this exclusive club had 123 members, including five dukes. The club later moved to Albemarle Street and then to Arlington Street before closing in 1777.

The Assembly Rooms on King Street

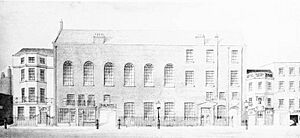

After the success of his clubs in Pall Mall, William Almack decided to build even grander rooms for entertainment. Between 1764 and 1765, he acquired land on the south side of King Street. The famous architect Robert Mylne designed the new assembly rooms.

On April 5, 1764, Mrs. Elizabeth Harris wrote that Almack was building "magnificent rooms" behind his house. Mylne's diary shows he worked with important people like Mr. James and Mr. Crewe on the club in King Street.

On November 15, 1764, Almack advertised the new rooms. He told subscribers that the building would be ready for the balls planned for the winter. He promised a strong, convenient, and elegant space. The advertisement described a large ballroom (90 feet long, 40 feet wide, and 30 feet high), separate rooms for tea and cards, and a supper room. Seven ladies had started subscription books, each for 60 subscribers. Each person paid ten guineas for admission to twelve balls per season. These rules show that fashionable ladies helped Almack start his venture and later had great power over who could enter the assemblies.

The assembly rooms opened on February 12, 1765, though they weren't fully finished until 1767. At first, it was a bit risky because another popular entertainment place, Carlisle House, was already established. Horace Walpole described the opening as somewhat empty, with many people having colds and the building still feeling new. He even mentioned that the Duke of Cumberland had trouble climbing the "vast flight of steps."

Despite this slow start, Almack's Assembly Rooms quickly became very popular. By February 1765, there were 300 to 400 subscribers. Ladies could lend their tickets to others, but men's tickets were not transferable. In March 1765, Gilly Williams wrote that "Our female Almacks flourishes beyond description." The main ballroom was completed in 1767.

William Almack passed away on January 3, 1781. He left his property, including the assembly rooms, to his son, William. His daughter, Elizabeth, married Dr. David Pitcairn. William Almack, the son, managed the business until 1792. The rooms' popularity declined around this time, possibly because the Pantheon opened in 1772.

In 1792, James Willis became the manager of the rooms. He was married to William Almack senior's niece. His family continued to manage the rooms until 1886–87. During the 1800s, the rooms were often called Willis's Rooms.

Almack's at Its Peak

By the early 1800s, Almack's was at its most famous. People came to Almack's to be seen and to show their high social status. It was a key place for gentlemen to find suitable brides. Getting a "voucher" to Almack's was more important than being presented at court.

The club's great reputation came from its special committee of the most powerful ladies in London's high society, known as the Lady Patronesses of Almack's. There were usually six or seven Patronesses at a time.

During the Regency period (when George IV was Prince Regent), some of the famous Lady Patronesses included:

- Amelia Stewart, Viscountess Castlereagh

- Sarah Villiers, Countess of Jersey

- Emily Clavering-Cowper, Countess Cowper

- Maria Molyneux, Countess of Sefton

- The Hon. Sarah Clementina Drummond-Burrell, later Lady Willoughby de Eresby

- Dorothea Lieven, Countess de Lieven (wife of the Russian ambassador)

- Maria Theresia, Countess Esterházy (wife of the Austrian ambassador)

A writer named Captain Gronow later described these ladies. He said Lady Cowper was very popular, while Lady Jersey could be rude. Madame de Lieven was proud, and Princess Esterházy was friendly. These ladies were very strict. They announced that gentlemen had to wear knee-breeches, white ties, and special hats to the assemblies. Once, the Duke of Wellington was turned away because he wore black trousers!

These powerful ladies made the Wednesday night balls very exclusive. Only those they approved could buy the annual "vouchers," which cost ten guineas and could not be transferred to someone else. A voucher was a small cardboard ticket that allowed the holder to get tickets for balls during the season. Subscribers could bring a guest if the guest was also approved. After supper was served at 11 o'clock, the doors closed, and no one else was allowed in, no matter how important they were.

If a person was approved by the Lady Patronesses, their social standing would greatly improve. Young ladies making their first appearance in London society often had their dance partners chosen by one of the Ladies. A poem about Almack's said that if you belonged to Almack's, you could do no wrong, but if you were banned, you could do nothing right.

Having a voucher for Almack's was the key to being part of the highest society. Losing a voucher was a huge social disaster. When Lady Caroline Lamb wrote a book that made fun of Lady Jersey, Lady Jersey banned Caroline from Almack's. This was a terrible social punishment, though the ban was later lifted. The Lady Patronesses met every Monday during the London social season (April to August) to decide who to remove or add to the membership. If someone was refused a ticket, they received a printed note saying the ladies were "sorry they cannot comply with his or her request," without giving a reason.

The rooms were not very big, which added to their exclusive feel. The average ball had about 500 people. The total number of members was limited to 700 to 800. Money alone could not get you into Almack's; it was meant to keep out the newly rich. Good manners and family background were more important than a noble title. Even a duke or duchess could be turned away if a patroness disliked them. It was said that many noble families tried, but failed, to get in. However, Thomas Moore, a poet with little money but excellent manners, was a member.

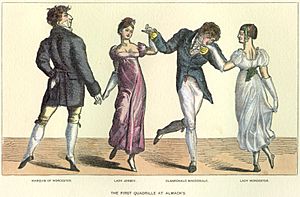

The ballroom had red ropes to separate the dancers. In the early 1800s, the music was provided by an orchestra from Edinburgh. To keep things proper, only English country dances and Scottish reels were allowed at first. This changed after the Regency began, when the quadrille and then the waltz were introduced. The quadrille was linked to Lady Jersey, and the waltz to Countess de Lieven. By 1837, only the gallopade and waltz were danced.

Almack's tried not to be like expensive private balls, so the food was simple. During the Regency, supper included thin slices of bread with butter and plain cake. Only tea and lemonade were served. By the 1830s, the quality of refreshments had declined, with people complaining the lemonade was too sour and the tea tasted like "chalk and water."

Decline of Almack's

By 1825, Almack's started to show signs of decline, even though it was still popular. A visitor named Prince Puckler-Muskau described it as a "large bare room, with a bad floor" and "wretched refreshments." He felt it was like an "inn-entertainment," with only the music and lighting being good.

The balls became less popular around 1835. By 1837, writers still said the Lady Patronesses had the power to make or break families' social standing. Being a member of Almack's was still a "sure passport to the very first society." However, by 1840, it was clear that the days of such extreme exclusivity were ending in England.

The Willis family continued to manage the rooms until 1886–87. The assemblies themselves are said to have ended around 1863.

Other Uses of the Assembly Rooms

From the very beginning, Almack's/Willis's Assembly Rooms were used for many events besides the Almack's Balls. Other balls were held there, too. In July 1821, a grand ball was given to celebrate the coronation of George IV. The King himself attended.

The rooms were also rented for public meetings, plays, concerts, and dinners. Famous musicians like Hector Berlioz conducted concerts there in 1848. The rooms hosted performances by singers like Mrs. Billington and Mr. Braham. In 1844, Charles Kemble gave readings from Shakespeare.

In 1851, during The Great Exhibition, the famous writer Thackeray gave lectures there about "The English Humorists." Charlotte Brontë, the author of 'Jane Eyre,' was in the audience.

Important political meetings also took place at Willis's Rooms. On June 6, 1859, a meeting of different political groups led to the formation of the modern Liberal Party. On June 25, 1865, the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF), an organization for studying the Holy Land, was founded there. Another important meeting on August 4, 1870, saw the creation of the British Red Cross.

The Dilettanti Society, a group interested in art and ancient Greece and Rome, also used the rooms for their regular dinners.

After Almack's

In 1886–87, a company bought the business, and the building was changed in 1892. Parts of it were used by auctioneers and art dealers, as well as a restaurant and other clubs.

The building was destroyed during World War II on February 23, 1944. Today, a block of offices called Almack House stands on the site, with a plaque remembering the original Almack's.

A new social club named "Almack's" was started in 1904 and was still active in 1911.

The Building

The original Almack's building was built in the Palladian style, which was popular at the time. It was on the south side of King Street. The outside of the building was simple, made of plain brick. The large ballroom was shown by its six tall, arched windows on the second floor.

Inside, the great room was described as being 100 feet long and 40 feet wide, and "one of the most beautiful in London." Pictures show that the walls had decorative columns and panels. The windows had fancy curtains, and large crystal chandeliers hung from the ceiling. Sofas lined the walls for guests to sit on, with a special sofa for the Lady Patronesses at the top end of the room. Besides the main ballroom, the building also had rooms for cards and supper.

In Fiction

Almack's appears in many novels from its time, especially "silver fork novels" which focused on high society. These include Almack's by Marianne Spencer Hudson (1827) and Almack's Revisited by Charles White (1828).

Almack's and its Lady Patronesses are also often featured in Regency romance novels, like those by Georgette Heyer. These books emphasize how important it was to get into Almack's for one's social standing. Even though the events themselves were often described as dull and the refreshments poor, being excluded from Almack's was the worst social failure.

Charles Dickens even mentioned Almack's in a speech in 1851, talking about how problems like dirt and disease could not be kept out of even the most exclusive places, like Almack's.

See Also

- List of London's gentlemen's clubs

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |