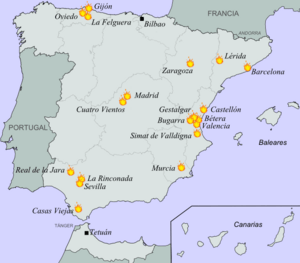

Anarchist insurrection of January 1933 facts for kids

Principle locations of the insurrection

|

|

| Native name | Insurrección anarquista de enero de 1933 |

|---|---|

| Date | 1 January 1933 |

| Location | Spanish Republic |

| Also known as | January 1933 revolution |

| Type | General strike |

| Cause | Poverty |

| Motive | Higher wages |

| Participants | CNT |

The anarchist insurrection of January 1933 was a major rebellion in Spain. It is also known as the January 1933 revolution. This event was the second big uprising led by the National Confederation of Labor (CNT). The CNT was a large workers' union in Spain. This happened during the time of the Second Spanish Republic, which was the government of Spain back then.

Contents

Why the Uprising Started

The CNT and another group called the Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI) used a special way of protesting. They wanted to show how difficult life was for many Spanish workers. People were very poor and struggled to live. The anarchists hoped these protests would spread and lead to a "libertarian revolution" across Spain. This meant they wanted a society without a government.

In December 1932, a meeting of the CNT was held in Madrid. Railway workers asked for support to start a big strike. They wanted higher wages. However, the railway workers later decided not to strike. They thought it would fail.

But a group in Catalonia, led by Juan García Oliver, liked the idea of an uprising. They wanted to stop the "Bourgeois Republic," which was their name for the government. They chose January 8, 1933, for the uprising to begin.

First Actions

The uprising actually started earlier, on January 1.

- In La Felguera, several powerful bombs exploded.

- In Seville, there were street fights. Shops and bars were robbed.

- In El Real de la Jara, protesters set fire to a local church.

- There was also looting in Lérida.

- In Pedro Muñoz, union members took over the City Hall. They announced "libertarian communism," which is a system where people share everything and there is no government.

On January 2, the Civil Guard (police) in Barcelona found a hidden bomb storage. They believed it belonged to the CNT. More explosives were found on January 3. On January 5, more bombs exploded in La Felguera and Gijón. Strikes by workers in Valencia also became more intense.

How the Uprising Spread

On January 8, members of the anarcho-syndicalist movement in Madrid tried to take over a military building. This led to a gunfight with the Civil Guard. In Barcelona, there were violent acts and shootings near the union's main office. Three bombs also exploded at the Madrid police headquarters.

Uprisings in Valencia

In the Valencia region, anarcho-syndicalist groups caused unrest in many towns. There was disorder in Valencia city and in towns like Riba-roja d'Ebre, Bétera, Benaguasil, and Utiel. Bombs exploded in Gestalgar.

In Bugarra, anarchists took control of the town after fighting with police. Several people died or were injured. They also declared "libertarian communism" there. Two police officers died in Bugarra. When the Civil Guard took back the town, they killed 10 farmers and arrested 250 more.

Uprisings in Other Areas

The unrest spread to Zaragoza, Murcia, Oviedo, and other areas. It was strongest in Andalusia, where many strikes began. In Seville, cars and trams were set on fire. Police faced several shootings. In La Rinconada, "libertarian communism" was announced.

In Casas Viejas, anarchist farmers also rose up and declared "libertarian communism." In response, local police attacked the town's residents. This event became a big political scandal because of the many deaths.

The main CNT committee had not called for this uprising. On January 10, they said the rebellion was "purely anarchist" and that the main group had not been involved. However, they did not condemn it. They felt it was their duty to show support. The CNT's official newspaper, Solidaridad Obrera, said the revolt was "neither defeated nor humiliated." They blamed the government and socialist politicians for using power against workers. The newspaper stated that the revolution "exists and will intensify." They believed that if one uprising was stopped, another would start.

End of the Uprising

The period of uprisings ended in December 1933. The last major event was in the small town of Bujalance, in the Province of Córdoba. Bujalance had a very strong CNT union with over 3,500 members.

The armed uprising by CNT members in Bujalance was very strong. The government had to send part of the army from Córdoba to stop it. Many workers died defending the town. After the uprising was stopped, there was harsh punishment. The CNT leaders in Bujalance, Milla and Porcel, were killed. This happened under a harsh rule called the Ley de Fugas, which allowed police to shoot prisoners and claim they were trying to escape. Other CNT and FAI members were sent to prison for a long time. Many of them were still in prison when the Spanish Civil War began.

Years later, in 1978, Juan García Oliver wrote about the January 1933 revolution. He believed he was the main person who started it. He called it "one of the most serious battles between libertarians and the Spanish State." He also said it caused the Republican and Socialist parties to lose support from most Spaniards.

See also

In Spanish: Insurrección anarquista de enero de 1933 para niños

In Spanish: Insurrección anarquista de enero de 1933 para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |