André Cailloux facts for kids

André Cailloux (1825–May 27, 1863) was a brave soldier during the American Civil War. He was one of the first black officers in the Union Army. He was also one of the first black officers to die in battle. Cailloux died heroically during a tough attack on Confederate forts. This happened during the Siege of Port Hudson. News of his bravery spread widely. It helped encourage many African Americans to join the Union Army.

People remembered him as a hero and a patriot for a long time. In 1890, a Civil War veteran named Colonel Douglass Wilson spoke about Cailloux. He said Cailloux's bravery deserved to be honored forever.

Contents

Who Was André Cailloux?

His Early Life

André Cailloux was born into slavery in Louisiana in 1825. He lived his whole life near New Orleans. As a young man, he learned to make cigars. He was owned by the Duvernay family until 1846. When he was 21, he asked to be freed. His owner supported this, and a group of white officials in New Orleans agreed. So, Cailloux became a free man.

New Orleans had a special group of people called "free people of color". These were people of mixed European and African heritage. They had been free for generations, going back to when the French ruled the area. They had more rights than enslaved people. Sometimes, white men had families with women of color. They might help their mixed-race children get an education or learn a trade.

In 1847, Cailloux married Félicie Coulon. She was also a free Creole woman of color. She had been born into slavery, but her mother bought her freedom. Cailloux and Coulon had four children. Three of them lived to be adults.

Life as a Free Man

After becoming free, Cailloux worked as a cigar maker. Before the Civil War started, he even opened his own cigar business. He wasn't rich, but he became a respected leader among the free people of color in New Orleans.

Cailloux loved sports and was known as one of the best boxers in the city. He also strongly supported the Institute Catholique. This was a school for black children, including orphans and children of free families. After he was freed, Cailloux learned to read. He probably got help from teachers at the Institute Catholique. He became fluent in both English and French.

By 1860, Cailloux was a well-known person in New Orleans. The city had about 10,000 free men of color. New Orleans was the biggest city in the South at that time.

André Cailloux's Military Service

Serving the Confederacy (Briefly)

When the Civil War began in 1861, Cailloux became a lieutenant in the Native Guard. This was a state militia formed to protect New Orleans. Free men of color had been part of local militias since the French colonial days. Cailloux was one of the first black officers in any North American military unit.

The Confederate Native Guard was made up entirely of free men of color from New Orleans. About 1,500 men volunteered. They asked the governor to join Louisiana's regular militia, and he agreed. White officers led the overall unit, but black officers led the companies. The soldiers elected their officers. The Confederate government did not provide uniforms or equipment. Cailloux took his duties seriously. His unit was known for being well-trained.

However, the Confederate Native Guard never saw active combat. When Union Admiral David Farragut captured New Orleans in April 1862, the Confederate forces left the city. The 1st Native Guard then officially broke up.

Joining the Union Army

Union General Benjamin F. Butler took charge of New Orleans. In September 1862, he decided to form an all-black Union Army regiment. This was called the 1st Louisiana Native Guard. Unlike the Confederate unit, this one included both free men and former slaves. General Butler needed more soldiers. He famously said he would "call upon Africa" for help if he didn't get reinforcements.

Cailloux joined the 1st regiment. Many soldiers in this unit only spoke French, so Cailloux's language skills were very helpful. He became a captain in Company E. His company was one of the best-trained in the Native Guard. Cailloux earned the respect of Colonel Spencer Stafford, the white officer leading the regiment.

Later, General Nathaniel P. Banks took over from Butler. He brought many more troops. By this time, the all-black Native Guard had grown to three regiments. Black officers served as lieutenants and captains. However, the top commanders (colonels and majors) were white. General Banks did not like having black officers. He tried to replace them all with white officers. He mostly succeeded with the 2nd and 3rd Regiments. But he could not do this with the 1st Regiment, where Cailloux served.

Many soldiers in the 1st Regiment had also been in the Confederate Native Guard. Cailloux and the other officers did not want to leave their men. They knew that white officers from New England were often treating black soldiers badly in the other two regiments.

The Siege of Port Hudson

The 1st Regiment of the Native Guard mostly did hard labor, like chopping wood and digging trenches. But in May 1863, General Banks moved his army to surround the Confederate forts at Port Hudson, Louisiana. Port Hudson was a very important fort on the Mississippi River. The Union wanted to control the Mississippi River.

While General Ulysses S. Grant attacked Vicksburg, General Banks led the siege of Port Hudson.

On May 27, 1863, General Banks launched an attack on Port Hudson. The Confederate positions were very strong. Cailloux was ordered to lead his company of 100 men in an attack. They faced two Confederate regiments with heavy cannons. Even though his company suffered many losses, Cailloux kept shouting encouragement in French and English. He led his entire regiment forward. A bullet hit his arm, leaving it useless. Even severely wounded, Cailloux kept leading the charge. Then, a Confederate cannon shell hit him, almost killing him.

His heroic actions were described by Rodolphe Desdunes, whose brother served under Cailloux:

This officer ran forward to his death with a smile on his lips. He cried, "Let us go forward, O comrades!" He charged the enemy's cannons six times. Each time he shouted, "Let us go forward, for one more time!" Finally, he fell from a deadly blow. He gave his last order to his officer, "Bacchus, take charge!"

After the battle, Confederate General Gardner asked for a truce to collect the bodies of the fallen Native Guard soldiers. General Banks refused, saying he had "no casualties in that area." Because of this, Cailloux's body lay on the ground for 47 days. Port Hudson finally surrendered on July 9, 1863. Few of the dead were identified. But Cailloux's body was recognized by a ring he wore.

Most of the Union dead were buried nearby. This area later became the Port Hudson National Cemetery. In 1974, it was named a National Historic Landmark.

His Funeral

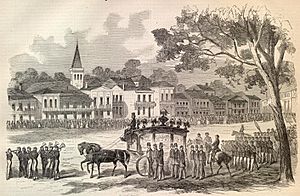

Cailloux's body was brought back to New Orleans. The story of his bravery had already reached the city. When his funeral was held on July 29, 1863, thousands of people attended. There was a long procession to honor him. His widow, Félicie, asked Father Claude Paschal Maistre to lead the service. Father Maistre was from France and was the only Catholic priest in the area who supported ending slavery. Cailloux was buried in Saint Louis Cemetery.

After Cailloux's death, his widow, Félicie, tried to get money from the U.S. government. This money was promised to veterans' families. After several years, she received a small pension. But she still died in poverty in 1874. She was working as a servant for Father Maistre at the time.

See Also

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |