Attrition warfare against Napoleon facts for kids

Attrition warfare is a type of fighting where one side tries to wear down the enemy's ability to fight. They do this by destroying their military supplies and soldiers in any way possible. This can include using a scorched earth policy (destroying everything useful), involving regular people in the war (a people's war), using guerrilla warfare (small, surprise attacks), and fighting many smaller battles instead of one big, decisive one.

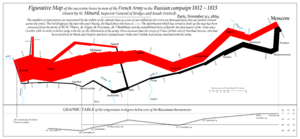

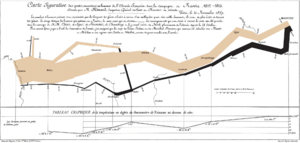

Elements of this kind of warfare were seen in the Peninsular war. The Russian attrition warfare against Napoleon began on June 24, 1812. This was when Napoleon's huge army, called the Grande Armée, crossed the Neman River into Russia. It ended on December 14, 1812, with the complete defeat of the Grande Armée. A famous drawing by Charles Joseph Minard shows how many soldiers Napoleon lost. Later, the Trachenberg Plan was used against Napoleon in Germany in 1813 and France in 1814. The Seventh Coalition finally defeated him at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. He was then sent away to Saint Helena, an island, where he died six years later.

Contents

- Scorched Earth Policy

- People's War

- Guerrilla Warfare

- Conventional Warfare

- Impact

- Portugal

- Spain

- Russia

- Kowno≈340,000 men

- Wilna≈330,000 men

- Glaubokoe≈280,000 men

- Bechenkoviski≈220,000 men

- Vitepsk≈190,000 men

- Smolenzk≈160,000 men

- Stawkovo≈140,000 men

- Viasma≈135,000 men

- Gehatz≈130,000 men

- Mojaisk≈100,000 men

- Moscow≈100,000 men

- Noilskoe≈90,000 men

- Borosk≈90,000 men

- Vereya≈80,000 men

- Smolenzk≈40,000 men

- Maladzyechna≈5,000 men

- Summary

- Strategies against Napoleon

- Civilian Losses

- See Also

Scorched Earth Policy

The "scorched earth" policy means destroying anything that could be useful to the enemy, like food, shelter, or supplies, when you retreat or leave an area.

Portugal

The Peninsular War began in Portugal in 1807 and lasted until 1814. In September 1810, a French army of 65,000 men, led by Masséna, tried to take over Portugal for the third time. They fought in the Battle of Bussaco. However, Wellington (a British general) pulled his army back south.

As the French army chased Wellington, they found a deserted land. Portuguese farmers had left their homes after destroying all the food they couldn't carry and anything else the French might use. This was part of the scorched earth policy.

On October 11, 1810, Masséna and his 61,000 men found Wellington's army. They were behind a very strong defensive line called the Lines of Torres Vedras. These were secret forts and defenses built to protect the only way to Lisbon from the north.

Because there was no food or animal feed, Masséna had to retreat north. He started on the night of November 14/15, 1810, looking for an area that hadn't been destroyed. The French stayed through February, even though it was one of the coldest winters in the Iberian Peninsula. But when hunger and diseases became too much, Masséna ordered a full retreat in early March 1811. He had lost another 21,000 men.

Russia

The French invasion of Russia began when they crossed the Neman River on June 24, 1812. Napoleon tried to conquer Russia with an army of 600,000 soldiers. But the Russian general, Barclay, kept pulling his army back to the east.

As the French army chased Barclay, they found a poor land with few people. The Russian army had destroyed all the food they couldn't take and anything else that might help the French. This was part of their scorched earth policy.

On September 7, 1812, Napoleon and 115,000 men found Kutuzov's army at Borodino. The Russians were in a weak defensive spot, blocking the only road to Moscow from the west. Napoleon defeated them and occupied a burning Moscow.

But Napoleon was forced to retreat, starting on October 19, 1812. He tried to find a path south that hadn't been destroyed by the scorched earth policy. However, Kutuzov successfully blocked this route at the Battle of Maloyaroslavets.

The French army had to retreat west along the same devastated path they had come from. Starvation, diseases like typhus, and hypothermia (due to a very cold Russian winter in November and December) became huge problems. Napoleon lost a total of 500,000 men in Russia.

Retreat of the Defending Army

The constant retreat of the Russian Army at the start of the war forced Napoleon's troops to march quickly in great heat to catch up. Their supply trains couldn't keep up and reach the soldiers in time.

A military writer named Clausewitz noted that a retreating army and a chasing army are in very different situations. The retreating army might have plenty, while the chasing army slowly starves. The army in retreat takes or destroys anything useful, creating scorched earth. The chasing army, however, must have everything brought to them by supplies that need to move faster than the army itself.

During the long retreat from Moscow to Poland, Kutuzov's main Russian army avoided following Napoleon directly. Instead, Kutuzov moved his army along parallel roads in untouched areas to the south. This helped him save many of his own soldiers.

People's War

A "people's war" is when ordinary citizens, not just soldiers, get involved in fighting an invading army.

Spain

On May 2, 1808, the Dos de Mayo Uprising happened in Madrid. This was a rebellion by the people of Madrid against Napoleon's troops who had taken over the city. The French forces fought back, using their Mamelukes of the Imperial Guard who wore turbans and used curved swords. This reminded the people of past conflicts and made them even angrier.

Russia

In the Patriotic War of 1812, Lieutenant-Colonel Denis Davydov suggested to his general, Pyotr Bagration, that they attack Napoleon's supply trains with a small group of soldiers. Davydov started this mission, working behind the Grande Armée. He dressed like a peasant and grew a beard to get the support of the Russian farmers. Davydov gave captured food and French weapons to the peasants and taught them how to fight a people's war.

Guerrilla Warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a type of fighting where small groups use surprise attacks, ambushes, and sabotage against a larger, less mobile army.

Spain

The word "guerrilla" actually came from the Peninsular War. This style of fighting was the most effective tactic used by the Spanish military. The guerrilla fighters kept large numbers of French troops busy over a wide area. They did this with much fewer soldiers, less effort, and fewer supplies than a regular army would need.

Russia

Davydov's small group captured French foraging parties and supply trains carrying food, horses, weapons, and ammunition. They also freed Russian prisoners and added them to their raiding party, giving them French horses and weapons. These actions started a wave of guerrilla warfare across the country.

Conventional Warfare

Conventional warfare is the usual way armies fight. It involves direct battles between the organized armies of two or more countries. The soldiers on each side are clearly defined and use weapons mainly to target the enemy's military forces.

Portugal

After testing the Lines of Torres Vedras in the Battle of Sobral on October 14, Masséna realized they were too strong to attack. He then moved his army into winter camps. Without food for his men and constantly bothered by Anglo-Portuguese hit-and-run attacks, he lost another 25,000 men. They were either captured or died from hunger or sickness before he finally retreated. This finally freed Portugal from French control.

Spain

The guerrilla fighters helped Wellington and his Anglo-Portuguese army win their conventional battles.

Austria

The battle of Aspern-Essling was the first time Napoleon himself was defeated in a major battle. This happened because the Austrians sent heavy barges floating down the Danube River, which cut Napoleon's supply lines by destroying his bridges.

Russia

Napoleon lost more than 500,000 men in Russia. But the losses reported in battles only add up to about 175,000. This shows that many more soldiers died from other causes like hunger, disease, and cold.

Germany, France, and Spain

The Trachenberg Plan was a war strategy made by the Allies in 1813. This plan suggested avoiding direct battles with Napoleon himself. Instead, the Allies planned to fight and defeat Napoleon's generals one by one. This would weaken his army while the Allies built up a huge force that even Napoleon couldn't beat.

Waterloo

Wellington chose a very strong defensive position at Waterloo. It was a long ridge running from east to west. Along the top of the ridge was a deep, sunken lane. Wellington placed his infantry (foot soldiers) just behind the top of this ridge. By using the reverse slope (a tactic he used often in the Peninsular War), Wellington hid most of his army's strength from Napoleon. Only his skirmishers (soldiers who spread out and fight in small groups) and artillery (cannons) were visible.

In front of the ridge, there were three fortified (strengthened) positions. On the far right was the Hougoumont (farmhouse). This house faced north along a hidden, covered path that could be used to bring in supplies. On the far left was the small village of Papelotte. Papelotte also controlled the road to Wavre, which the Prussian army would use to send help to Wellington. In front of the rest of Wellington's line was the farmhouse of La Haye Sainte. On the other side of the road was an old sand quarry, where the 95th Rifles (a British rifle unit) were placed as sharpshooters. Wellington's army was positioned in a way that made it very difficult for any attacking force.

Impact

Portugal

Masséna's campaign in Portugal cost him at least 25,000 men. Also, as many as 50,000 Portuguese farmers died from hunger in 1810 because of the scorched earth policy.

Buçaco≈65,000 men

On September 27, 1810, Marshal Masséna began his campaign with his 65,000-strong army (called l'Armée de Portugal).

Torres Vedras≈61,000 men

By October 11, 1810, after losing 4,000 men at the Battle of Buçaco, Masséna arrived at Torres Vedras with 61,000 men.

Fuentes de Oñoro≈40,000 men

On May 3, 1811, when Masséna finally returned to Spain in April 1811, and before he fought the battle of Fuentes de Oñoro, he had lost another 21,000 men. Most of these losses were due to hunger, severe illness, and disease. The fact that the Iberian Peninsula had one of its coldest winters ever made things even worse.

Spain

In the Peninsular War, Napoleon lost at least 91,000 men in battle, and 237,000 were wounded. If you include those who died from disease, accidents, and exhaustion, the total number of French deaths might have been between 180,000 and 240,000.

Russia

To understand how many soldiers were lost due to the Russian Fabian strategy (a strategy of avoiding direct battle and wearing down the enemy), the numbers of soldiers in the Grande Armée are taken from Minard's Map. This map was based on French records. Later groups of soldiers who joined or left the main army are subtracted to get a clearer picture of losses. The numbers are rounded to the nearest 10,000 to make them easier to compare. Because of this adjustment, Napoleon started at Kowno with about 340,000 men, not the 422,000 shown on Minard's map. The numbers of French soldiers mentioned below are meant to show how much attrition warfare affected Napoleon's part of the Grande Armée, which left Russia with fewer than 5,000 soldiers.

Kowno≈340,000 men

On June 26, 1812, the Grande Armée crossed the Neman River. Their supplies, mainly flour, brandy, and biscuits, were supposed to be transported by water up to Wilna. The army did not organize water transport for men and horses. Also, since the invasion started in summer, the troops were supposed to find food for their horses from the fields ready for harvest.

Wilna≈330,000 men

By June 30, 1812, the Russian army was retreating deeper into Russia, burning their own supply stores as they went. They avoided big battles. By July 6, the weather changed from extreme heat to very cold, with heavy rain and thunderstorms. Wilna became the French supply base, with huge stores filled by boats on rivers. On July 11, the French army marched quickly to follow the Russians. The heat was intense. By July 16, French supply by boat was working well. The Russian army kept retreating, burning their supplies.

The first major problem for the French army was feeding their horses. They couldn't find enough good quality food for all of them in the poor countryside. Thousands of horses died, including those used for transport. This reduced the army's ability to carry supplies.

The second major problem was the poor quality of the roads from Wilna onwards, which Napoleon hadn't considered. The bad roads turned into mud, slowing down the supply trains even more. Since supply trains needed to be faster than the marching army, transport from Wilna to the front lines almost stopped because of the bad roads and fewer horses.

The third major problem was that soldiers got sick with waterborne diseases like dysentery. This happened because French soldiers drank any available water from dirty streets and had no brandy left to purify it, as supplies couldn't reach them fast enough. The increasing heat and fast marches required even more water for soldiers and horses.

Glaubokoe≈280,000 men

By July 23, 1812, the Russian army retreated after burning their supplies. The countryside was described as beautiful, with large monasteries. Two of these held 2,400 sick French soldiers.

Napoleon's fourth main problem was that his soldiers had to go on foraging trips to find food to survive without supplies. These trips were perfect for soldiers to desert, which increased the losses of the Grande Armée even more.

Bechenkoviski≈220,000 men

By July 25, 1812, the French army was still following the Russian army eastwards.

The foraging trips by the Grande Armée, and now the growing number of lawless deserters, made the poor peasants hate them even more. This created strong feelings for a merciless people's war. The young, inexperienced soldiers were not used to living off the land, which had already been destroyed by the retreating Russian army and then again by their own leading French troops, like the Guard. They got sick, deserted, or starved.

Vitepsk≈190,000 men

By July 31, 1812, Vitepsk was taken, and supply stores were filled, and hospitals were set up. By August 4, the Grande Armée was sent by Napoleon to rest. The heat was extreme. By August 7, ten days of rest greatly helped the soldiers and their horses. The harvest was excellent.

Smolenzk≈160,000 men

By August 21, 1812, the Russian army left Smolenzk burning and continued retreating east. By August 23, the heat was still extreme. It hadn't rained for a month. Smolenzk became the third supply base, surrounded by rich fields with plenty of food and fodder. The Russians formed a militia of poorly armed peasants.

Stawkovo≈140,000 men

By August 27, 1812, the Russian army, as it retreated, burned bridges and destroyed roads. The heat was extreme, and it hadn't rained for a month.

Since Barclay had lost the trust of the Russian Emperor, the nobles, the army, and the people by always retreating and not fighting, Mikhail Kutuzov was made Commander-in-chief of the Russian army. Kutuzov, who was 67, simply planned to outlast Napoleon.

Viasma≈135,000 men

By August 31, 1812, a little rain had fallen, and the weather was expected to be good until October 10, 1812.

Gehatz≈130,000 men

By September 3, 1812, food and water were no longer a problem.

Kutuzov officially looked for a battleground to the east because he wasn't allowed to retreat further east, knowing his predecessor had been fired for doing just that. The result was that the number of French soldiers kept dropping steadily without a fight, simply from having to chase the Russian army eastwards.

Mojaisk≈100,000 men

By September 10, 1812, after losing the Battle of Borodino, the Russian army opened the road to Moscow for the Grande Armée.

Even though Kutuzov's army had lost, it hadn't been destroyed. He claimed a victory and retreated south of Moscow near Tarutino after the council at Fili. He waited for Napoleon to retreat. He increased the guerrilla warfare by the Cossacks and the people's war by the peasants, slowly weakening the French army. His own army was strengthened with men, horses, weapons, ammunition, food, fodder, water, warm clothes, and boots from the rich southern areas near Moscow. The horses were given special shoes with spikes, as was common in Russia.

Moscow≈100,000 men

By September 16, 1812, the Russian Governor Fyodor Rostopchin had sent away all the firefighters and ordered Moscow to be set on fire on September 14.

By September 17, a strong wind spread the fire very quickly, as 80% of the houses were made of wood. Huge, well-stocked warehouses burned, but most cellars were untouched. The French army was recovering from hunger, thirst, and endless marches with plenty of wine, brandy, and food. However, there wasn't enough fodder for the horses, and their numbers decreased. The temperature was like autumn. Soldiers found some furs for the winter.

By September 20, after a few days, the fire died down, but 75% of the city was burned. The weather was rainy. By September 27, the first frosts appeared. The weather was similar to late October in Paris. The French army believed the rivers wouldn't freeze until mid-November. By October 9, the sun felt warmer than in Paris. By October 14, the weather was very fine. The first snow fell. The French army estimated they would reach winter quarters in 20 days.

No organized supply of furs and heavy boots had been given to every French soldier. The Grande Armée did not put special shoes with spikes on all horses, except for the experienced Polish cavalry. This meant horses struggled on icy roads.

The transport of wounded French soldiers from Moscow to Smolenzk, Minsk, and Mohiloff began.

The guerrilla war by the Cossacks against the Grande Armée's supply trains and the people's war against French foraging parties became more intense.

The peasants were told that the French had burned Moscow, their sacred city. Also, Napoleon disrespected churches by looting them in an organized way. The hatred of the Russian peasants grew even more.

Noilskoe≈90,000 men

By October 20, 1812, the army received orders to bake biscuits for twenty days, and Napoleon finally left Moscow on October 19, 1812. The Kremlin was mined to blow it up. The weather was very fine.

Russian prisoners who couldn't keep up were shot, which increased the hatred of the Russian people even more.

Borosk≈90,000 men

By October 23, 1812, Napoleon ordered the destruction of the fortress and military buildings. The Grande Armée was now marching into the rich southern part of Moscow. The weather was extremely good.

Kutuzov and his Russian army were waiting on the road to Kaluga.

Vereya≈80,000 men

By October 27, 1812, it was the end of autumn for Russia. The Grande Armée won the Battle of Maloyaroslavets, and during the night, the Russian army retreated. But Napoleon decided to turn back from marching south and instead walk northwest.

Napoleon made a strange detour on Minard's map. This detour caused a delay of a few days until he reached the road to Smolenzk. This was the same road his own Grande Armée had already stripped of anything useful on the way to Moscow. Because of the delay, the food they had taken from Moscow was almost gone.

Smolenzk≈40,000 men

By November 11, 1812, the Russian winter began on November 7, covering the ground with snow. The roads became extremely slippery and dangerous for horses without special spiked shoes. Many soldiers without furs, heavy boots, or food, but loaded with stolen goods, died from cold and exhaustion. Sleeping outside at night without a tent became deadly. Huts had been burned for firewood. The Cossacks attacked almost every small unit, even deliberately preventing the French army from sleeping.

The peasants killed many groups of stragglers, sometimes in terrible ways. Many French soldiers died from hunger because no supplies were available, and foraging was extremely dangerous due to the peasants and the vast distances to find anything in the destroyed landscape. When the French administration finally collapsed, French stragglers fought in Smolenzk for food and looted their own supply stores, destroying more than they gained.

Maladzyechna≈5,000 men

By December 3, 1812, the cold increased a week later to -20°C (which is -4°F). The roads were covered with ice, and more than 30,000 horses died. The Grande Armée abandoned and destroyed a large part of their cannons, ammunition, and provisions.

The Cossacks and peasants had killed or captured unknown numbers of isolated individuals. In Minard's map, some groups of soldiers who had been detached came back and briefly increased the number of French soldiers. If these numbers are correctly subtracted, as at the beginning in Kowno, the actual number of remaining soldiers would be below 5,000. Napoleon's part of the Grande Armée had been destroyed by attrition warfare.

Summary

Russia

Napoleon and his Grande Armée usually got their supplies by taking them from the land and its people as they advanced. This worked well in places like Germany, Italy, and Austria, which had many people, rich farmlands, and good paved roads. However, this strategy was less successful in the Peninsular War in Spain and Portugal.

In the sparsely populated areas of Russia, there wasn't enough food and water. Combined with extreme temperatures and Russia's scorched earth strategy, this led to a disaster that Napoleon ignored. The guerrilla warfare by the Cossacks against supply trains caused many soldiers and horses to die, as they were forced to eat and drink from dirty sources, leading to widespread disease.

Feeding a large number of horses with supply trains was impossible at that time because a horse's daily food ration weighed about ten times as much as a man's. The army simply couldn't gather the huge amount of supplies needed by foraging in the poor and devastated Russian countryside, especially with the fierce people's war against them.

Strategies against Napoleon

| 1805 | C3 | C3 | C3 | C3 | |||||

| 1806 | C4 | C4 | C4 | ||||||

| 1807 | C4 | C4 | C4 | PW | PW | PW | |||

| 1808 | PW | PW | PW | PW | PW | ||||

| 1809 | C5 | C5 | C5 | PW | PW | PW | PW | ||

| 1810 | PW | PW | PW | PW | |||||

| 1811 | PW | PW | PW | PW | |||||

| 1812 | RC | RC | RC | RC | RC | PW | PW | PW | PW |

| 1813 | C6 | C6 | C6 | C6 | C6 | PW | PW | PW | PW |

| 1814 | C6 | C6 | C6 | C6 | C6 | PW | PW | PW | PW |

| 1815 | C7 | C7 | C7 | C7 | C7 |

| XX | Under Napoleon's command |

| I, II | France's two-front war (fighting on two sides) |

| XX | Napoleon was personally involved in the fighting |

| XX | Attrition Warfare used against Napoleon |

| XX | Conventional Warfare used against Napoleon |

| XX | Trachenberg Plan used against Napoleon |

| C3 | War of the Third Coalition |

| C4 | War of the Fourth Coalition |

| C5 | War of the Fifth Coalition |

| C6 | War of the Sixth Coalition |

| C7 | War of the Seventh Coalition |

| PW | Peninsular War |

| RC | Russian Campaign |

Civilian Losses

Russia

Napoleon himself wrote in his memoirs that 100,000 Russian men, women, and children died in the woods because of the fire of Moscow. It is thought that around half a million civilians were killed in total during the Russian campaign.

See Also

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |