Barthélemy Boganda facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Barthélemy Boganda

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Boganda in 1958

|

|||||||

| President of the Council of Government of the Central African Republic | |||||||

| In office 6 December 1958 – 29 March 1959 |

|||||||

| Succeeded by | Abel Goumba | ||||||

| Personal details | |||||||

| Born | 1910 Bobangui, Oubangui-Chari |

||||||

| Died | 29 March 1959 (aged 48–49) Boda District, Central African Republic |

||||||

| Cause of death | Plane crash | ||||||

| Nationality | Central African | ||||||

| Political party |

|

||||||

| Spouse |

Michelle Jourdain

(m. 1950) |

||||||

| Children | 3 | ||||||

|

|||||||

Barthélemy Boganda (around 1910 – 29 March 1959) was an important politician and activist from the Central African Republic. He worked for his country's independence when it was still a French colony called Oubangui-Chari. He became the first leader, or Premier, of the Central African Republic when it became an independent territory.

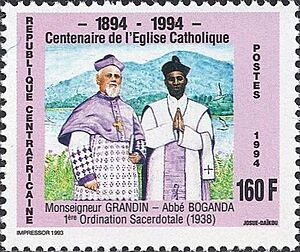

Boganda grew up in a farming family. After his parents died, Catholic missionaries adopted him and made sure he got an education. In 1938, he became a Catholic priest. After World War II, he was encouraged to enter politics. In 1946, he became the first person from Oubangui-Chari to be elected to the National Assembly of France. There, he spoke out against racism and unfair treatment by the colonial government.

He returned home and started a political group called the Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa (MESAN) in 1949. This group became very popular with villagers and farmers. Boganda later left the priesthood to marry Michelle Jourdain. He continued to fight for equal rights for Black people in the territory. As France gave its colonies more freedom, MESAN won local elections, and Boganda gained power in the government.

In 1958, French Prime Minister Charles de Gaulle suggested creating a "French Community." This would allow France's colonies to stay connected to France. Boganda supported joining after he was promised that Oubangui-Chari could still become fully independent later. He wanted to join as part of a larger group of territories called the "Central African Republic." He hoped this would make them stronger and richer. He even dreamed of a "United States of Latin Africa," including other countries. This bigger dream did not happen. On December 1, 1958, Boganda declared Oubangui-Chari as the Central African Republic. He became its first Premier. He started making plans for new laws and the next election. Sadly, he died in a plane crash on March 29, 1959, while flying to Bangui. Experts found traces of explosives in the plane, but a full report was never released. The possibility that he was assassinated remains a mystery. The Central African Republic became fully independent in 1960. His death is remembered every year in the country.

Early Life and Education

Not much is known about Boganda's very early life. He was born around 1910 in Bobangui, a village near the Lobaye River. His father was a village chief and owned palm farms. His mother was his father's third wife. When Boganda was young, French companies were using forced labor in Central Africa. This caused a lot of hardship for the local people.

Both of Boganda's parents died when he was young. His father was reportedly killed by colonial forces. His mother might have been killed for not collecting enough rubber. Boganda was then cared for by relatives. In 1920, he got smallpox. One day, he was left alone and met a French patrol. They misunderstood his words and thought "Boganda" was his name. A French officer took him to an orphanage in Mbaïki.

A missionary then took him to a mission school in Bétou. There, Boganda learned to read and write in Lingala. He was a very good student. In 1921, he moved to the main mission in Bangui, the capital. He was baptized Barthélemy in 1922. He later said that becoming a Christian helped him feel free and connected to all people. He learned French and farming skills.

By 1924, Boganda wanted to become a priest. He went to different seminaries, which are schools for priests, in the Belgian Congo and Brazzaville. He finished his studies in Bangui and Yaoundé, French Cameroon. He was the first African student at the school in Yaoundé.

On March 17, 1938, Boganda became a priest. He taught at a school in Bangui. During World War II, he wanted to join the French Army, but his bishop said he was needed for church work. From 1941 to 1946, he worked in the Grimari region, teaching the Banda people. He wanted them to stop polygamy and send girls to school. Sometimes, he used strong methods, which caused problems. He also felt that colonial officials and some missionaries treated him unfairly because of his race. These issues led to him being moved to another mission in Bangassou in 1946.

Political Journey

Joining the French Assembly

After World War II, Boganda was encouraged to enter politics by his bishop. People in Oubangui-Chari wanted him to represent them. On November 10, 1946, he was elected to the National Assembly of France. He was the first person from Oubangui-Chari to join this assembly. He won almost half of all the votes.

Boganda joined a political group called the Popular Republican Movement. He arrived in Paris wearing his priest's clothes. He hoped for strong support from French politicians for his ideas. But he was disappointed by the lack of help for his people.

He left his political group in 1950 and became an independent politician. He was re-elected to the National Assembly in 1951 and 1956. He spoke out against the unfairness of colonialism and the lack of justice in French Equatorial Africa. After 1956, he stopped attending the Paris parliament often, but he remained a deputy until 1958.

Boganda was frustrated by the problems in Oubangui-Chari. He criticized French rule, especially racism. He spoke about unfair arrests, low wages, forced cotton farming, and how Black people were not allowed in some places. He was against colonialism but still supported connections between France and Oubangui-Chari. He also spoke out against communism. He tried to pass laws to reform land ownership and stop forced labor. However, his strong criticisms made other deputies upset, and his ideas were not often accepted.

Building a Movement in Oubangui-Chari

Boganda felt that his work in the National Assembly was not changing things enough back home. So, he decided to take direct action in Oubangui-Chari. In 1948, he started a co-operative project called SOCOULOLE. It aimed to help farmers earn more money and improve their lives. This group provided food, clothes, housing, medical care, and education. However, it faced financial problems and closed later.

On September 28, 1949, Boganda created the Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa (MESAN). This was a large political party. He wrote its rules, saying it wanted to "develop and free the black race." The party supported freedom and equality for Africans. Boganda used the Sango language phrase zo kwe zo, which means "every human being is a person." This became a very important idea for his movement. He often spoke about the simple life before colonialism, and his messages were popular with farmers. People also liked that he was not afraid to challenge colonial officials.

MESAN's activities made the French government and trading companies angry. These companies did not like the end of forced labor or the rise of Black nationalism. They saw Boganda as a threat. French colonists tried to create their own political groups to stop MESAN, but they were not as popular.

Boganda used the respect people had for the Catholic Church to help his political work. He met and fell in love with Michelle Jourdain, a French secretary. In 1949, he was removed from the priesthood because he wanted to marry. However, he remained a Catholic. They married on June 13, 1950, and had three children.

In 1951, Boganda was arrested after a dispute between his co-operative and Portuguese merchants. He was accused of "endangering the peace" and sentenced to two months in prison. He used this arrest as part of his campaign for re-election to the French National Assembly, which he won.

Working with the French

In 1952, the French government appointed new officials who were more open to reforms. This helped ease tensions between Boganda and the local government. In 1953, Charles de Gaulle visited Bangui. Boganda refused to meet him, but de Gaulle did not publicly criticize Boganda.

In 1954, a riot broke out in Berbérati after two Africans working for a European died. The crowd demanded justice. The governor asked Boganda to help. Boganda spoke to the crowd and promised that "the same justice would be given to white as to black." The crowd then calmed down. This event showed the administration how serious the racism problem was.

After this, MESAN continued to grow stronger. Boganda praised the French administration's work in education and health. He said that doctors, administrators, and colonists were friends. He also started his own coffee farm and encouraged others to do the same.

Self-Rule and MESAN Government

In June 1956, France passed a law called the Loi-cadre Defferre. This law gave French colonies more self-rule. In November, Boganda became the first Mayor of Bangui.

On February 4, 1957, Oubangui-Chari officially became semi-autonomous. It had a Council of Government and a Territorial Assembly. On March 31, MESAN won all the seats in the Assembly. Boganda chose Abel Goumba, a doctor and his former student, to be the Vice President of the Council. Boganda himself became President of the Grand Council, focusing on politics for the whole region.

A European minister named Roger Guérillot was in charge of economic affairs. He tried to increase the number of Africans in government roles. Boganda encouraged him to criticize French officials. Boganda also suggested that French administrators should leave, but admitted it would take time to train Africans to replace them.

Boganda wanted to build a railway from Bangui to French Chad. To make this possible, he believed Oubangui-Chari needed to produce much more. So, he asked Guérillot to create a plan to boost farming. Guérillot proposed a huge plan to grow more coffee, cotton, and ground-nuts. But French colonists and banks did not invest in it. Farmers also disliked the plan, seeing it as a return to forced labor. The plan failed and damaged Boganda's reputation.

De Gaulle and the French Community

In May 1958, Charles de Gaulle became Prime Minister of France again. He wanted to create a new French constitution and rethink France's relationship with its colonies. Boganda was not included in the group writing the new constitution, which upset him.

De Gaulle proposed a new "French Community" that would include the African colonies. Boganda was worried this would stop independence. In August, de Gaulle met with African leaders in Brazzaville. Boganda asked that the new French constitution recognize the colonies' right to independence. De Gaulle promised that joining the Community would not stop Oubangui-Chari from becoming independent later. A vote was planned in each colony. De Gaulle warned that voting "no" would mean immediate independence but also an end to all French aid.

On August 30, Boganda told MESAN leaders to vote "yes" for the new constitution. He traveled around Oubangui-Chari, telling people that the French would stay a little longer to fix the problems of colonization. On September 28, 98% of voters supported the new constitution.

Dreams of African Unity

Boganda worried that if Oubangui-Chari became independent alone, it would be too weak. He wanted to create a united state in Central Africa. He wrote that a united government would save money and help all citizens.

He imagined a "Central African Republic" that would include Oubangui-Chari, Congo, Gabon, and Chad. He believed this needed to happen quickly. Boganda even dreamed of a larger "United States of Latin Africa," including the Belgian Congo, Ruanda-Urundi, Angola, and Cameroon.

Boganda sent people to Gabon, Chad, and Congo to see if they were interested in joining. Gabon, the richest state, refused. Chadian leaders also said no. The leader of Congo was interested, but his position was weak. Because Gabon refused, France was hesitant to support the federation. By November 28, all other territories decided to join the French Community as separate countries. Disappointed, Boganda declared only Oubangui-Chari as the Central African Republic on December 1.

The Central African Republic is Born

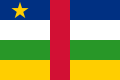

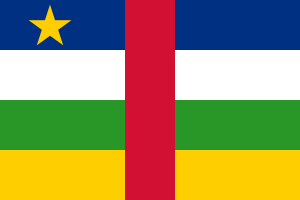

The Central African Republic adopted a flag designed by Boganda. It included a star, the French colors, and colors from other African flags. He also wrote the words for the national anthem, "La Renaissance". On December 6, Boganda became the first President of the Council of Government (Premier).

Boganda made changes to his government. He sent Roger Guérillot to France and replaced him with David Dacko. The new government's first goal was to write a constitution. This document was democratic and allowed the country to join a wider union later. The draft was approved on February 16, 1959. Boganda then started making big changes to the government's structure. He also prepared for new elections. MESAN won all the seats easily.

Death

Plane Crash

On March 29, 1959, Boganda boarded a plane in Berbérati to fly to Bangui. The plane went missing. Its wreckage was found the next day in the Boda district. All nine people on board, including Boganda, died. Boganda's body was found in the pilot's cabin.

French investigators examined the crash site. A report was never officially published. However, a French magazine reported that traces of explosives were found in the wreckage. The French High Commissioner tried to stop this news from spreading in the Central African Republic. The exact cause of the crash has never been officially confirmed. Many Central Africans believed it was an assassination. Some suspected foreign businessmen or even the French secret service. Historians believe that foul play was very likely.

What Happened Next

People in the country were mostly calm after Boganda's death. Some of his followers believed he was not truly dead and would return. His funeral was held on April 3 outside the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Bangui. Thousands attended. Abel Goumba became the interim leader.

David Dacko, with support from French officials, became the new leader. Goumba eventually stepped aside. Dacko focused on running the government. The Central African Republic gained full independence from France on August 13, 1960. Dacko became President and eventually made MESAN the only political party in the country.

Lasting Impact

Remembering Boganda

In June 1959, the Legislative Assembly called Boganda the "Father of the Nation." He received several honors after his death. The Boganda National Museum was opened in 1966 in his former home in Bangui. A school and a street were also named after him. A statue of him stands in the capital. Boganda Day is celebrated every year on March 29 to remember his death.

Many people in the Central African Republic still believe in Boganda's special powers. His memory is very important in the country's history. His phrase, zo kwe zo ("every human being is a person"), is on the country's coat of arms. The country's 2004 constitution mentions his principle of "ZO KWE ZO." Even though his specific political ideas are not always studied, his actions and spirit continue to inspire people.

Historians describe Boganda as a very talented and important political leader from French Africa. His death was a great loss for the country. It may have made it easier for Jean-Bédel Bokassa to take over the government later in 1966.

Boganda's life is written about in French history books. Many Central African writers praise him greatly. His ideas are part of studies about political philosophies. In English history, he is often mentioned when discussing his dream of a "United States of Latin Africa."

Images for kids

-

Boganda (right) receiving French Prime Minister Charles de Gaulle in Brazzaville in August 1958 to discuss the political future of Oubangui-Chari

-

Boganda designed the flag of the Central African Republic.

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |