Battle of Barrosa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Barrosa |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Peninsular War | |||||||

Battle of Chiclana, 5 March 1811, Louis-François Lejeune |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

||||||

The Battle of Barrosa happened on March 5, 1811. It's also known as the Battle of Chiclana or Battle of Cerro del Puerco. This battle was part of a plan by British, Spanish, and Portuguese forces to break the French siege of Cádiz during the Peninsular War.

During the battle, a single British army group managed to defeat two French army groups. They even captured a special French flag called a French Imperial Eagle. Even though the British won this battle, it didn't end the siege of Cádiz right away. The French were able to get back to their positions and continue the siege.

Contents

The Siege of Cádiz

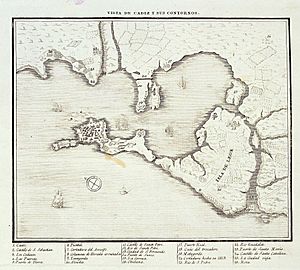

In early 1810, the French army began to surround the city of Cádiz in Spain. Cádiz was a very important port and where the Spanish government was located at the time. The French wanted to capture it.

At first, Cádiz didn't have many soldiers. But a Spanish general named Alburquerque brought 10,000 of his men to help defend the city. This made Cádiz much stronger and harder for the French to attack.

The Spanish government asked Viscount Wellington (a famous British general) for help. Soon, British and Portuguese soldiers arrived, making the city's defenses even stronger. By May, there were 26,000 Allied soldiers in Cádiz, while the French had about 25,000.

In early 1811, the French army around Cádiz got smaller. Their commander, Marshal Victor, had to send many of his soldiers to help with another battle. This made the Allies think it was a good time to try and break the siege.

Planning the Attack

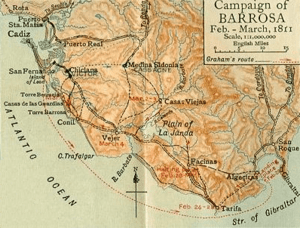

The Allies decided to send a large force by sea from Cádiz to a town called Tarifa. From there, they would march north to attack the French from behind. This force included about 8,000 Spanish soldiers and 4,000 British soldiers. The overall command was given to a Spanish general, Manuel la Peña.

Another Spanish general, José Pascual de Zayas y Chacón, was supposed to lead 4,000 Spanish troops out of Cádiz at the same time. They would cross a floating bridge to attack the French from the front.

The British soldiers, led by Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Graham, left Cádiz on February 21, 1811. Bad weather made them land at Algeciras instead of Tarifa. They then marched to Tarifa and met up with more troops. General la Peña's Spanish troops also arrived there a few days later.

The Allied army started marching north on February 28. Their plan was to attack the French at Medina-Sidonia. But scouts reported that Medina-Sidonia was too strong. So, General la Peña changed the plan. He decided they would march along a different road that led directly to Cádiz.

This change of plan, plus more bad weather and la Peña's decision to march only at night, caused delays. Meanwhile, General Zayas in Cádiz launched his attack as planned on March 3, not knowing about the delays. The French quickly pushed Zayas's troops back, and the floating bridge had to be pulled back.

Marshal Victor, the French commander, learned about the large Allied force marching towards Cádiz. He realized their path was predictable. So, he set a trap. He sent one French army group to block the road to Cádiz. Two other French army groups hid in a forest, ready to attack the side of the Allied army as they faced the first French group.

On March 5, the Allies reached a hill called Cerro del Puerco (also known as Barrosa Ridge). Spanish scouts saw the French blocking the road. The Spanish vanguard (front part of the army) attacked and pushed the French back across a creek. But General la Peña stopped his troops from chasing the French.

Graham's British and Portuguese soldiers stayed behind on Barrosa Ridge. Their job was to protect the back and right side of la Peña's main force.

The Battle Begins

After clearing the road to Cádiz, General la Peña told Graham to move his troops forward. Graham didn't want to leave Barrosa Ridge because it would leave his army open to attack. So, five Spanish battalions and one British battalion were left to hold the ridge. Graham's division then moved north through a pine forest. The trees made it hard to see, so they were marching without knowing what was ahead.

French Surprise Attack

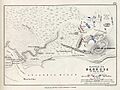

Marshal Victor was upset that his first group didn't block the road for longer. But he still believed his main force could push the Allies into the sea. He saw that most of the Spanish troops were facing his first group. Then he heard that Barrosa Ridge was empty. He realized this was a chance to capture the important hill.

Victor ordered one of his generals, Ruffin, to take the ridge. Another general, Leval, was told to attack Graham's troops in the woods. French cavalry was sent around the hill to attack from the coast.

Victor's plan worked quickly. Ruffin's advance made the five Spanish battalions on the ridge run away. Only the British battalion was left. When French cavalry appeared, the Allied cavalry also retreated. Barrosa Ridge was taken by the French without a fight. Ruffin quickly set up cannons on the hill.

Fighting on Barrosa Ridge

The British battalion that had retreated from the ridge tried to go back up. They faced heavy fire from Ruffin's cannons and soldiers. Many were lost, and the rest scattered for cover.

Meanwhile, another British brigade, led by General Dilkes, came out of the woods. They advanced up the hill from a different side, where the French couldn't see them as well. This meant the French cannons couldn't hit them easily. Dilkes's brigade reached the top of the ridge without many losses.

The French attacked with their soldiers in thick columns. But the British, fighting in a line formation, stopped the French columns. Both sides fired at each other. Marshal Victor brought up more French soldiers, but they also faced heavy fire and stopped just a few meters from the British line. The French soldiers began to fall back. The British battalion that had scattered earlier also started firing again. The entire French force broke and ran down the hill.

Leval's Attack in the Woods

While Dilkes was fighting on Barrosa Ridge, other British light companies moved through the woods towards General Leval's French division. The French were not expecting an attack and were marching in columns. The sudden appearance of British skirmishers (soldiers who fight in a scattered way) caused confusion. Some French regiments thought there was cavalry and formed squares (a defensive formation).

British cannons, which had moved quickly through the woods, arrived and fired shrapnel at the French. The French then formed their usual attacking columns. British light companies and Portuguese soldiers fought them, holding them back until another British brigade, led by Wheatley, formed a line at the edge of the woods.

Leval's French division had 3,800 men, while the Anglo-Portuguese line had 1,400 men with cannons. Even though the French had more soldiers, they thought they were facing a larger force. Wheatley attacked right away. The French needed time to change from columns into lines, but Wheatley didn't give them that time.

One French column broke after just one British volley (a mass firing of muskets). The 8th French regiment lost about half its men and its eagle (a special flag). This was the first eagle captured by British forces in the Peninsular War! Sergeant Patrick Masterson of the 87th British regiment captured it. Wheatley's brigade kept pushing forward, breaking another French battalion after three charges. The French fled.

French Retreat

Ruffin's and Leval's French divisions ran towards a nearby lagoon. Marshal Victor managed to stop their disorganized retreat. He used a few remaining battalions to cover his forces while they reorganized and retreated. But Graham also managed to get his tired men in order. He brought them, along with the cannons, to attack Victor's new position.

The French soldiers were very nervous. When some British cavalry attacked a group of French dragoons (cavalry) and pushed them into their own infantry, the French soldiers panicked and ran away again.

Throughout the battle, General la Peña refused to help his British and Portuguese allies. He knew the French were attacking Graham, but he stayed in his defensive position. He thought the French would win. Even after hearing the British had won, la Peña still refused to chase the retreating French.

What Happened Next

Graham was very angry with la Peña. The next morning, Graham collected his wounded soldiers and trophies and marched his troops into Cádiz. La Peña later blamed Graham for losing the campaign. However, Wellington, the main British commander, praised Graham's actions.

If the Allies had chased the French right after the battle, or the next morning, the siege of Cádiz likely would have ended. The French were in a state of panic. Marshal Victor had even made plans to blow up most of his siege forts and retreat to Seville. But the Allies did not advance.

To Victor's surprise, a cavalry patrol on March 7 found no Allied forces. By March 8, just three days after the battle, Victor had reoccupied his siege lines. The siege of Cádiz continued for another 18 months. It finally ended on August 24, 1812, when the French had to retreat after losing the Battle of Salamanca.

Even though their general acted poorly, the Spanish success at Almanza Creek and Graham's victory at Barrosa Ridge greatly boosted Spanish morale. La Peña faced a military trial for not chasing the French. He was found not guilty but was removed from command. Graham's criticism of his Spanish allies meant he was transferred to Wellington's main army.

The Battle of Barrosa was a British victory in terms of fighting and casualties. Graham's troops, even though they had marched all night and day, defeated a French force nearly twice their size. The British, Portuguese, and German soldiers under Graham lost about 1,240 men. The French lost around 2,380. The Spanish had 300-400 casualties.

However, the Allies' failure to follow up their victory meant the French could reoccupy their siege lines. So, strategically, the battle didn't achieve its main goal of ending the siege of Cádiz. Victor even claimed it as a French victory because the siege continued.

Legacy

In November 1811, the British Prince Regent ordered a special medal to be made. This medal was given to the senior British officers who fought in the "brilliant Victory" at Barrosa.

Four ships of the Royal Navy have been named after the battle, including HMS Barrosa (1812), launched a year after the battle.

An officer named Lieutenant William Light, who later became the Surveyor General of South Australia, named a range of hills in the new colony the Barossa Range. This was in memory of the battle. Today, this area is famous for its wine, known as the Barossa Valley (wine).

- Grant, Philip, A Peer Among Princes – the Life of Thomas Graham, Victor at Barrosa, Hero of the Peninsular War, 2019, ISBN: 978-1526745415

In fiction

- Cornwell, Bernard, Sharpe's Fury: Richard Sharpe and the Battle of Barrosa, March 1811, HarperCollins, 2006, ISBN: 978-0-06-053048-8.

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Chiclana para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Chiclana para niños

Images for kids

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |