Cornish rebellion of 1497 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Cornish rebellion of 1497 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Statue of Michael Joseph the Smith and Thomas Flamank in St Keverne Cornwall. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Rebels from Cornwall and South-West England | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

Michael An Gof |

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| At least 15,000 | At least 25,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Estimated 1,000 dead | Unknown | ||||||

The Cornish rebellion of 1497 (in Cornish: Rebellyans Kernow) was a big uprising in England. It started in Cornwall and ended with a battle near London on June 17, 1497. This event is also known as the First Cornish rebellion.

Most of the rebels were from Cornwall. But they also got support from people in Devon, Somerset, and other English counties. The rebellion happened because King Henry VII made people pay high taxes. He needed the money to fight a war against Scotland. Cornwall was hit especially hard by these taxes. The king had also recently stopped the legal operation of their tin-mining industry.

The rebellion ended with the rebels losing the battle. Their main leaders were put to death. Many other people who took part were also punished. This rebellion might have made Perkin Warbeck choose Cornwall later that year. He was a person who claimed to be the rightful king. He tried to overthrow Henry VII in what is called the Second Cornish uprising of 1497. However, 11 years later, King Henry fixed the main problem for Cornwall. He allowed tin mining to start again legally. He also gave the tin miners some freedom to manage their own affairs.

Contents

Why the Cornish Rebellion Happened

King Henry VII made some decisions in 1496 and 1497. These decisions made life harder for many of his people. This was especially true for those living in Cornwall.

Problems with Tin Mining

In 1496, the king stopped the tin-mining industry in Cornwall. He did this because of disagreements over new rules. The king worked through the Duchy of Cornwall to do this. The tin miners had special rights and freedoms. These included not having to pay certain royal and local taxes. These rights were given to them by King Edward I in 1305. Stopping these rights was a big problem for Cornwall's economy.

New Taxes and Hardships

In 1496 and 1497, King Henry VII faced a threat. The Scottish king and Perkin Warbeck were planning to invade England. To pay for defense, Henry VII demanded a lot of money from his people. First, he made them give him a forced loan. Then, he asked for double the usual taxes. He also added a special tax called a subsidy. Cornwall had to pay more than most other areas. This was especially true for the forced loan.

The Rebellion Begins

The first protests started in a place called St Keverne. This area is on the the Lizard peninsula. People there were already upset with Sir John Oby. He was the tax collector for that area.

Leaders of the Uprising

Because of King Henry's new taxes, two men started an armed revolt. They were Michael Joseph (An Gof), a blacksmith from St. Keverne, and Thomas Flamank, a lawyer from Bodmin. Flamank said the rebellion's goal was to remove two of the king's advisors. These advisors were Cardinal John Morton and Sir Reginald Bray. The rebels believed these men were responsible for the king's tax policies. By focusing on the advisors, they hoped their actions would not be seen as treason. Instead, they wanted it to look like a request for change.

Marching Towards London

An army of about 15,000 rebels started marching. They went into Devon, where they got more supplies and new fighters. However, fewer people in Devon joined the rebellion. This was probably because their tin miners had accepted new rules in 1494. So, they had avoided the punishments given to the Cornish miners.

The rebel army then entered Somerset. In Taunton, they reportedly killed a tax collector. In Wells, they were joined by James Touchet, a nobleman. He had military experience and was made their leader. The rebels continued their march towards London. They passed through Salisbury and Winchester.

Approaching London

King Henry had been getting ready for a war with Scotland. But when he heard about the rebels getting close to London, he changed his plans. He sent his main army of 8,000 men to stop them. This army was led by Lord Daubeny. Another group was sent to the Scottish border. Lord Daubeny's army set up camp near London on June 13. At the same time, many people in London were worried. They got ready to defend their city. The next day, 500 of Daubeny's soldiers fought with the rebels near Guildford.

Until then, the rebels had not faced much armed resistance. But they also had not gained many new fighters since leaving Somerset. Instead of going straight to London, they went south. Flamank thought they would get support from Kent, which is south-east of London. So, after Guildford, they moved to Blackheath. This is a high area south-east of the city. They reached it on June 16. But no uprising happened in Kent. Instead, Kentish forces were gathered against them. These forces were led by loyal nobles.

The king now had a very large army in London. The rebels' situation looked bad. Many of them felt worried and disagreed that night at Blackheath. An Gof wanted to fight. But many others wanted to give up. Their original goal was not to fight the king directly. It was to make him change his advisors and tax rules. Thousands of rebels left the camp that night.

The Battle of Deptford Bridge

The Battle of Deptford Bridge happened on June 17, 1497. It took place in an area now called Deptford in south-east London. This battle was the final event of the Cornish Rebellion. The rebels had not gained enough new support. They also had not moved fast enough to surprise the king. Now, the rebels were on the defensive. The king had an army of about 25,000 men. The rebels, after many people left, had 10,000 or fewer. They also did not have cavalry or cannons, which were important for armies at that time.

The King's Plan

The king had told everyone he would attack the rebels on Monday, June 19. But he actually attacked early on Saturday, June 17. He thought Saturday was his "lucky day." His army was split into three groups. They were set up to surround the high ground of Blackheath. This is where most of the rebel army was still camped.

The Fight

The strongest of the king's groups, led by Lord Daubeny, attacked along the main road from London. They had to cross Deptford Bridge. The rebels were ready for them. They had placed guns and archers there. These weapons caused many injuries to the king's soldiers who were trying to secure the bridge. However, the king's soldiers managed to drive away the rebel gunners and archers.

Lord Daubeny then led the attack up to the rebels' main position. He was so brave that he got separated from his men. He was surrounded by the rebels and captured for a short time. The rebels could have killed him. But they let him go unharmed. The rebels were greatly outnumbered and surrounded. They were not well trained or equipped. They also had no cavalry. Their fight was now hopeless. They probably wanted to reduce the punishments that would follow the battle.

The rebels were completely defeated. Their leaders, Thomas Flamank and Lord Audley, were captured on the battlefield. Michael Joseph (An Gof) tried to escape. He wanted to find safety in a church. But he was caught before he could get inside.

After the Battle

After the battle, the King visited the battlefield. He made his bravest soldiers knights. Then he went back to London. There, he also rewarded others, like the mayor. They had helped guard London and feed the army. He then went to St Paul's Cathedral for a special service to give thanks.

The king announced that soldiers who captured rebels could keep or sell their possessions. They could also ask for money from the prisoners' families to release them.

What Happened After the Rebellion

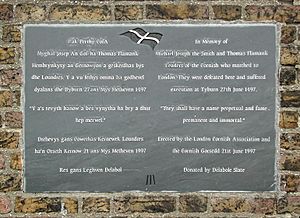

An Gof and Flamank were put to death in Tyburn on June 27, 1497. It is said that An Gof spoke before he died. He said he would have "a name perpetual and a fame permanent and immortal." They were sentenced to a very harsh death. But the king showed them some mercy. They were only hanged before their bodies were cut up. Their heads were put on London Bridge. Flamank's body parts were displayed on four of the city gates. An Gof's body parts were sent to Cornwall and Devon. However, some historical records say the king changed his mind. He decided not to display An Gof's body parts in Cornwall. He did not want to make the Cornish people even angrier.

Audley, as a nobleman, was beheaded on June 28 at Tower Hill. His head was also displayed on London Bridge.

After the rebellion, the king's agents collected large fines from Cornwall. This made many parts of Cornwall poor for years. Land was taken from some people and given to those loyal to the king. But after this time of punishment, the king helped Cornwall in 1508. He forgave the tin miners for breaking the rules. The old rules were removed. The Cornish Stannary Parliament was given back its power. This meant they could approve any new rules for the tin industry.

Remembering the Rebellion

In 1997, a special march took place. It was called Keskerdh Kernow (which means "Cornwall marches on" in Cornish). People walked the same route the rebels took from St. Keverne to Blackheath, London. This was to celebrate 500 years since the Cornish Rebellion. A statue of the Cornish leaders, Michael An Gof and Thomas Flamank, was put up in An Gof's village of St. Keverne. Special plaques were also put up in Guildford and on Blackheath.

The name of Cornwall's rugby league team, the Cornish Rebels, was inspired by this rebellion.

In 2017, a memorial bench was put up in Deptford. It was designed by artist Gary Drostle.

There is also a stone monument in Bodmin. It remembers the rebels Thomas Flamank and Michael Joseph.

See also

In Spanish: Rebelión de Cornualles de 1497 para niños

In Spanish: Rebelión de Cornualles de 1497 para niños

- Second Cornish uprising of 1497

- List of topics related to Cornwall

- Cornwall portal

- Prayer Book Rebellion