Battle of Havana (1748) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Havana (1748) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of Jenkins' Ear | |||||||

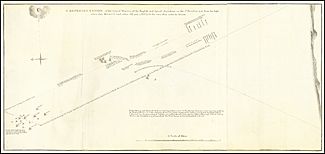

Sir Charles Knowles's Engagement with the Spanish Fleet off Havana, Richard Paton |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5 fourth-rates | 4 fourth-rates, 1 frigate |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 59 killed and 120 wounded | 1 ship captured 1 ship destroyed 1 ship heavily damaged 86 dead and 197 wounded 470 captured |

||||||

The Battle of Havana was a big sea fight between the British and Spanish navies. It happened near Havana, a city in Cuba, during a conflict called the War of Jenkins' Ear. This battle took place from October 12 to October 14, 1748.

The British squadron was led by Admiral Charles Knowles. The Spanish squadron was commanded by Admiral Andrés Reggio y Brachiforte. The British managed to push the Spanish fleet back towards their port. They even captured one Spanish ship, the Conquistador. Another Spanish ship, the Africa, ran aground and was later blown up by its own crew.

Even though Admiral Knowles had a clear advantage, he didn't manage to win a complete victory. This battle was the last major fight in the War of Jenkins' Ear. This war had become part of a bigger conflict called the War of the Austrian Succession.

Contents

Why did the Battle of Havana happen?

By 1747, the fighting between Great Britain and Spain in the Americas had reached a standstill. Neither side could fully defeat the other. British forces had tried to take over Spanish colonies but failed. Spain also couldn't capture any British colonies.

Naval battles were important in this period. For example, George Anson of the Royal Navy became famous for raiding Spanish areas. Britain also blocked the port of Toulon, stopping a combined French and Spanish fleet.

In April 1747, Admiral Sir Charles Knowles became the main commander at the Jamaica naval base. He had tried to capture Santiago de Cuba but didn't succeed. After fixing his ships at Port Royal, Knowles sailed out. He hoped to find Spanish treasure ships near Cuba. He wanted to capture them before news of peace between Spain and Britain arrived. News of peace between France and Britain had already come, but not yet for Spain. So, Knowles continued his mission.

On September 30, Knowles met Captain Charles Holmes from HMS Lenox. Holmes told him he had seen a Spanish fleet a few days earlier. Admiral Andrés Reggio, leading the Havana Squadron, left Havana on October 2. His goal was to protect Spain's shipping routes from British attacks. His ships had fewer sailors than needed, so they brought soldiers and new recruits to help.

How the Battle Unfolded

On the morning of October 1, 1748, Admiral Reggio's Havana Squadron was sailing north near Havana. Reggio thought he saw a Spanish convoy (a group of ships traveling together). He wanted to protect them, so he ordered his ships to sail directly towards what he saw.

At the same time, Admiral Sir Charles Knowles, leading the British Jamaican squadron, saw a group of ships heading straight for him. He quickly ordered his own ships to form a line, sailing north. He wanted to create enough distance to get into a better position for attack. This position is called the "weather gauge," meaning having the wind at your back, which gives you an advantage.

Reggio soon realized that the "convoy" he saw was actually the British squadron. He immediately ordered his ships to turn downwind. This helped them form a line, almost matching Knowles's direction. However, this move meant Reggio lost the weather gauge, while Knowles was now in a good position to get it. Knowles then signaled his ships to "lead large," meaning to sail with the wind on their side, heading towards the Spanish.

As the wind changed in the afternoon, the two leading British ships, Canterbury and HMS Warwick, drifted closer to the Spanish center. The Spanish ships then started firing at them from a distance. Knowles had told his ships not to fire until closer. But despite this order, the lead British ships fired back at the Spanish.

Because Warwick was moving slowly, Knowles ordered HMS Canterbury to pass it at 3 PM. It wasn't until 4 PM that Knowles's flagship, HMS Cornwall, and HMS Lenox joined the fight. These British ships heavily damaged the Spanish Conquistador. It soon lost its front and middle masts and could barely move.

Cornwall waited to fire until just after 4 PM. When it got very close, it fired a powerful broadside (all guns on one side of the ship firing at once) into Reggio's flagship, Africa. Ahead, HMS Strafford fired many broadsides into Conquistador. Lenox also joined the attack from behind. At 4:30 PM, HMS Strafford got very close and fired a devastating broadside into the Conquistador. After this, the Conquistador could not fight back.

In less than an hour, Conquistador was so damaged it had to leave the Spanish line. Its captain and two officers were dead. It soon surrendered to Strafford. However, Strafford did not send boats to take control of the ship. Reggio saw this and forced Conquistador to raise its flag again by firing at it from his ship, Africa. HMS Cornwall then came to help, with an angry Knowles on board, along with Canterbury. Finally, Conquistador surrendered again to Cornwall.

By 5:30 PM, HMS Warwick was finally ready to catch up to the Spanish. At this point, every Spanish ship tried to escape. Strafford and Canterbury tried to capture Africa, while HMS Tilbury and HMS Oxford chased the Spanish ship Invencible.

By 9:00 PM, Invencible seemed to have stopped firing, but the British ships were too weak to stop it from escaping. HMS Cornwall had slowed down because it lost its front topsail. Strafford and Canterbury kept hitting Africa until its main and middle masts fell. However, as night fell quickly, the Royal Navy ships couldn't keep chasing. They stopped at 11 PM to make quick repairs and sail back out to sea.

Of Reggio's Squadron, four ships returned to Havana's harbor. The Conquistador had been captured. The Invincible was badly damaged but just barely escaped capture. The Africa, Reggio's flagship, was dismasted (lost its masts) and so damaged that it went into a small bay 25 miles east of Havana for repairs. Knowles, with the lead ships of his squadron, Cornwall and Strafford, headed eastward on October 14. They soon found Africa and started firing. The stranded crew of Africa cut its anchor ropes, set the ship on fire, and ran it ashore. An hour later, with more help from British cannon fire, the Africa blew up.

What happened after the battle?

Knowles then met up with the rest of his ships. Before he could plan any more attacks, a Spanish small boat was stopped. From it, they learned that the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle had been signed. This meant the war in Europe was over. Knowles dropped off the Spanish prisoners in Cuba and sailed to Jamaica with the one ship he had captured.

The Battle of Havana showed how important it is for a group of ships to work together. Because Knowles's squadron didn't work together perfectly, they couldn't get close enough to the Spanish ships quickly. If Reggio had wanted to, he could have easily escaped the British by sailing west. The British squadron also started firing too early, when they were too far away. The four Spanish ships that survived had more than 150 sailors dead and a similar number seriously wounded.

Both commanders, Knowles and Reggio, were criticized by their own navies for how they acted during the battle. Knowles was criticized for not using all his ships to win a complete victory. Knowles blamed the captains under his command, except for David Brodie of the Strafford and Edward Clark of the Canterbury. This led to the captains asking for Knowles to face a formal review of his conduct, called a court-martial. Even though Knowles won the battle, he was still criticized because of this review. Despite this, Knowles eventually became an admiral in 1758.

Reggio faced a military court review by Spanish naval authorities. He was accused of thirty different things related to the battle, especially about the destruction of his own flagship, Africa.

Ships that Fought in the Battle

An officer from the HMS Lenox wrote a letter on November 23, 1748. This letter listed the ships and their commanders involved in the battle. It was later published in The Naval Chronicle.

British Ships

| Ship | Guns | Commander | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tilbury | 60 | Captain Charles Powlett | |

| Strafford | 60 | Captain David Brodie | |

| Cornwall | 80 | Rear-Admiral Charles Knowles Captain Polycarpus Taylor |

|

| Lenox | 70 | Captain Charles Holmes | |

| Warwick | 60 | Captain Thomas Innes | |

| Canterbury | 60 | Captain Edward Clark | |

| Oxford | 50 | Captain Edmond Toll | Not in the main battle line |

Spanish Ships

| Ship | Guns | Commander | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invencible | 74 | Rear-Admiral Benito Spínola Captain Antonio Marroquin |

|

| Conquistador | 64 | Captain Tomás de San Justo † | Captured |

| África | 74 | Vice-Admiral Andrés Reggio | Later sunk by its own crew |

| Dragón | 64 | Captain Manuel de Paz | |

| Nueva España | 64 | Captain Fernando Varela | |

| Real Familia | 64 | Captain Marcos Forrestal | |

| Galga | 36 | Captain Pedro de Garaycoechea | Not in the main battle line |

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de La Habana (1748) para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de La Habana (1748) para niños