Battle of Refugio facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Refugio |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Texas Revolution | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Republic of Texas | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| José de Urrea Juan José Holzinger |

Amon B. King † Lt. Colonel William Ward |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,500 men | 148 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 150 Killed, 50 Wounded | •16 killed, 15 executed during the battle •81 captured one week later, 55 of them executed at the Goliad Massacre and 26 spared execution |

||||||

The Battle of Refugio was a fight during the Texas Revolution. It happened from March 12 to 15, 1836, near Refugio, Texas. Mexican General José Urrea led about 1,500 soldiers. They fought against Texan forces led by Amon B. King and Lieutenant Colonel William Ward. The Texan side had about 148 American volunteers. This battle was part of the Goliad Campaign and ended with a Mexican victory. It also weakened the Texan resistance.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

Mexico's government, led by President Antonio López de Santa Anna, was changing. It moved from a system where states had more power (federalist) to one where the central government had all the power (centralized). Santa Anna's strict rules, like canceling the Constitution of 1824, made many people angry. This led to revolts across Mexico.

Revolts in other parts of Mexico were quickly put down. But in the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas, people were still upset. The part called Texas had many English-speaking settlers, known as Texians. In October 1835, the Texians started fighting. This became the Texas Revolution.

By the end of 1835, all Mexican troops had left Texas. Santa Anna decided to stop the rebellion. He gathered a large army of over 6,000 soldiers. He also passed a rule saying that foreigners fighting against Mexico would be treated like pirates. This meant they could be killed if captured.

Santa Anna led most of his army to San Antonio. He sent General José de Urrea with 550 soldiers to the Texas Gulf Coast. Urrea's job was to protect the army's side and stop supplies from reaching the Texan rebels. This mission became known as the Goliad Campaign.

Before the Fight

Colonel James Fannin and his men had made their fort stronger at Presidio La Bahía. They called it "Fort Defiance." News arrived that other Texan groups had been captured in earlier battles. This made the volunteers at Goliad confused and unsure what to do.

On March 7, Lewis Ayers brought news from Refugio, a town about 25 miles (40 km) south of Goliad. A week earlier, a group of Tejanos (Mexican residents) who supported the central government had damaged the town. This group, called the Victoriana Guardes, was led by Captain Carlos de la Garza. They camped outside Refugio.

Some Anglo families who supported Texas independence were still in Refugio. They were afraid of being captured by the Mexican army or harmed by de la Garza's men. Fannin agreed to send help to get these families out.

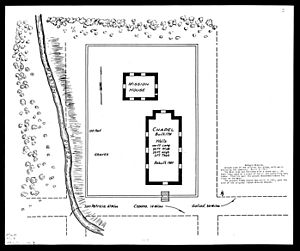

On March 11, Captain Amon B. King led 28 men and some carts to Refugio. They arrived that evening and stayed at Mission Nuestra Senora del Refugio. Some Anglo families were already there. The mission had been abandoned by the church years ago. Local Irish settlers had made some basic repairs to the building.

The next morning, King went to a ranch where Lewis Ayers' family was staying. King arrested six Tejanos he believed were stealing from empty homes. He then heard that other Tejanos were stealing about 8 miles (13 km) south. King took half his men to chase them. They rode into a surprise attack by de la Garza's men and Karankawa Indians. The Texians fought their way out and returned to the ranch. All the families were then taken to the mission in Refugio.

Soon after, some of Urrea's cavalry arrived in Refugio. Mexican troops and de la Garza's men, about 100 in total, surrounded the mission. King sent a message to Fannin asking for more soldiers. Earlier that day, Fannin had learned that Mexican troops had taken the Alamo, and all its defenders had been killed.

The Battle Begins

Fannin sent Lt. Colonel William Ward and his Georgia Battalion to help. This group, along with Captain Peyton S. Wyatt's company, left early on March 13. Fannin wanted Ward to quickly gather the civilians and return to Goliad. He told Ward to avoid fighting if possible. The soldiers carried only a small amount of ammunition because they didn't expect a long battle.

Ward's group arrived in the early afternoon after a fast march. They found the mission being attacked by Mexican cavalry and local militia. These forces pulled back after Ward's men fired a few shots.

Even though Ward had broken the siege, he and Captain King disagreed about who was in charge. King insisted he should lead because he arrived first, even though Ward was a higher-ranking officer. Ward wanted to leave the mission quickly and return to Goliad with the civilians. King refused. He said he was going to attack a ranch that was helping the Mexican militia.

King left with his men and some others from Ward's group early on March 14. This decision by King would cause big problems for Fannin's entire force.

After King left, more of Urrea's troops arrived and surrounded the mission again. Late on March 13 or early on March 14, a group of men under Captain Wyatt went on patrol. They found a small group of Mexicans asleep and attacked them, killing 20-25.

Early on March 14, after King had left, the Georgians heard gunshots in the distance. Thinking King might need help, Ward sent two companies forward. They stopped after a short distance when they saw a large group of the regular Mexican Army. They had to return to the mission. Soon after, a group getting water for the mission came under fire but managed to bring back a lot of water.

As the Mexican army moved around the mission, Ward's men tried to make the mission stronger. They used a low rock wall from an animal pen to cover one side of the mission. The rest of the Georgians guarded the windows and made small holes in the church walls to shoot from. They saved their ammunition by not shooting much at first.

Meanwhile, King and his men had not gone far when they met a much larger Mexican force. They had to hide in a wooded area about 2 miles (3.2 km) from the mission. Soon, Mexican militia found them, and fighting started. King's group fought well from behind trees and rocks, causing many losses for the enemy. But they eventually ran out of ammunition. Mexican reports say King and his men surrendered to the militia. They were then given to the regular Mexican army and were killed near the Refugio mission on March 15 or early on March 16, 1836.

Back at Refugio Mission on the morning of March 14, more Mexican army units arrived. They kept shooting at the mission. This shooting was not very effective at first. The Mexican army mostly had muskets, which were not very accurate. Their gunpowder was not the best, and the soldiers did not have much shooting practice.

The shooting continued for about an hour as the Mexicans moved closer. Because they had little ammunition, Ward told his men to wait until the enemy was very close. Soon, a small cannon joined the attack, but the thick stone walls of the mission could not be broken.

When Mexican troops gathered in the open, 200 to 300 yards away, the Georgians opened fire with their rifles. Their shots were very effective. They kept causing losses as Urrea's troops advanced. The attack was well planned, with many units attacking different parts of the mission. Some Mexican groups reached the low stone wall around the mission. But none reached the church or crossed the far wall. The Georgia Battalion stopped three or four major attacks.

Only three members of the Georgia Battalion were wounded. One soldier was badly hurt, another was shot in the leg, and Colonel Ward was hit by falling stones from cannon fire. Estimates of Mexican losses vary from 150 to 600 killed and wounded. General Urrea's own reports changed over time, but he first said about 200 were killed or wounded.

Ward sent messengers to Fannin for new orders as the fighting slowed on the evening of March 14. Later that night, Edward Perry, a Texan prisoner, was sent by General Urrea with a demand to surrender. Perry told Ward that his messengers and one from Fannin had been captured. He also gave Ward a letter from Fannin. This letter ordered Ward to go to Victoria, where Texan forces were supposed to gather.

During that long day, more Mexican units kept arriving. By evening, Urrea had about 1,200 soldiers, including infantry and cavalry, plus 100-200 Mexican militia, and several cannons. General Urrea showed off his large numbers, hoping to scare Ward into surrendering. The Georgians watched the Mexican bands and troops setting up. Even though the enemy was much stronger and no help was coming, Ward sent Mr. Perry back to Urrea with his answer: "The Georgians would not surrender."

With almost no bullets or gunpowder left, Ward planned to follow Fannin's orders. That night or early on March 15, during a heavy rainstorm, the Georgia Battalion quietly slipped through the Mexican lines. They carried their rifles and very little ammunition. The wounded, some civilians, and about 25 Mexican prisoners stayed behind. Ward and most of his men escaped towards Copano, then turned towards Victoria.

At Refugio Mission, the Mexican forces did not know the Texans had escaped until daylight. The wounded and Anglo civilians prepared for the Mexican army's arrival. Their belongings were taken, but Mexican officers soon arrived and brought order. The wounded were protected for a time, and women and children were kept safe. Later, some soldiers returned and killed the wounded. It is not known if they were ordered to do this. Some historians believe that the good treatment of the Mexican prisoners by the Texans helped calm the Mexican army's desire for revenge. A German-Mexican officer, Juan José Holzinger, saved Lewis T. Ayers, Francis Dieterich, Benjamin Odlum, and eight men from local families. The families who feared harm were allowed to return home safely.

To avoid Mexican cavalry, Ward and his men had to travel through trees and thick bushes along creeks and swamps. They walked in deep water for hours each day. It rained often, and the nights were cold. Soldiers had to rest and sleep in trees. They kept going for days, eating frogs, snakes, and whatever they could find. They shot a cow and rested for a while but had to return to the swamps when Mexican forces approached.

Even though they did not know the area well, they struggled toward Victoria, where they thought Fannin would be. Survivors heard gunshots from the direction of Coleto Creek two days before they got near Victoria. Men started to struggle and got lost or simply did not wake up when the group moved on. Some of these lost men were lucky, but many were found by Mexican forces, who rarely took prisoners.

At Victoria, they found no time to rest. It was full of Urrea's troops. The group had to scatter after a short fight with Urrea's cavalry. They stayed off the main roads and moved toward Lavaca Bay. Ten of them eventually escaped. The rest were surrounded and captured on March 22 by Urrea, two miles from Dimmit's Landing.

Ward and his men were told that Fannin had surrendered, and they would get the same terms. They were marched back to Victoria. There, Holzinger again saved twenty-six men by making them laborers for Urrea. Urrea had left Colonel Telesforo Alavez in charge of Victoria. Señora Francita Alavez also helped her husband make sure these captive laborers would live.

The remaining men were sent to Goliad by March 25. They joined a wounded Fannin and the rest of the Goliad soldiers. Two days later, the men were told they would march to the Texas coast and freedom. Instead, they were marched a mile from their old fort and killed under direct orders from General Santa Anna. Out of the 81 soldiers under Ward's command who escaped Refugio, 55, including Ward, lost their lives. The other 26 were saved by Señora Alavez and Colonel Alavez.

What Happened and Why

Captain King and Lieutenant Colonel Ward failed to get the Anglo civilians out of Refugio. King's choice to disobey orders from his superior officer, Fannin, had serious consequences. Colonel Fannin's decision to wait for King and Ward to return also allowed General Urrea to catch the rest of the Texan forces at Coleto Creek.

If King and Ward had escaped Refugio and rejoined Fannin, it might have been a larger fight. This would likely have caused more losses for Mexico but probably would not have changed the final outcome. Fannin had received orders from General Sam Houston to leave Goliad and go to Victoria as soon as possible. A quick retreat and more troops could have kept Fannin's force strong.

However, Fannin was slow to leave Goliad before Urrea arrived. This led to the Battle of Coleto. Fannin showed a lack of organization needed to move a large army. But it was not entirely his fault. The revolutionary government had not given him the transportation and supplies needed to move his troops.

Even with these problems, the Texan volunteers at Refugio and Coleto Creek caused significant damage to General Urrea's army. This greatly slowed his advance. It stopped his forces from helping the main Mexican army at San Jacinto.

Also, Lieutenant Colonel Ward's successful escape from Refugio Mission on the night of March 14–15, 1836, was a notable military achievement. His seven-day retreat through rivers, swamps, and bayous was very difficult. Ward and his officers kept their unit together. Even though they were poorly equipped, lacked food, and were cold, the Georgia Battalion continued to act as a fighting force for Texas.

General Urrea had to use hundreds of his men to find and fight the Georgians. Ward and the Georgia Battalion fought off at least two Mexican cavalry units and kept moving toward Victoria. Ward followed Fannin's orders to reach Victoria. This was something Fannin, with a much larger force and shorter distance, could not do.

When Ward found Victoria held by the enemy, he kept trying to find a safe place for his men. They got within two miles of Dimmit's Landing before being surrounded again by the Mexican Army. Witnesses say the Georgia Battalion fought one last attack using their last ammunition, bayonets, and rifles as clubs.

Only then did General Urrea offer surrender terms. These were the same terms Fannin had accepted a few days earlier, vaguely offering a chance to return to the United States. Ward felt his men could still reach the woods and swamps and keep going. He told his officers he was against surrendering. But the Georgia Battalion was a volunteer unit, so he let his officers and men decide. Hungry, tired, and suffering, the men voted to accept the Mexican General's terms.

Through Ward's leadership, the Georgia Battalion remained an effective fighting force for one very important week. They fought against an enemy force that was 12 times their size. This gave Houston and his army seven more valuable days.

What We Remember

In the public square in Refugio, there is the King Monument. It honors Captain King and his men. In the early 1900s, this square was called King's State Park.

In the 1850s, the Texas Governor and Legislature agreed to build a monument to honor the Georgia Battalion. This was to thank Georgia for their sacrifice and for providing weapons and supplies to Texas. For a time, Texas said it was too poor. Then construction was delayed again. Georgia is still waiting for this promised monument. However, the city of Albany, Texas built a fountain as a monument to Ward and the Georgia Battalion in 1976.

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Refugio para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Refugio para niños