Presidio La Bahía facts for kids

|

Presidio La Bahía

|

|

Presidio La Bahía as it stands today

|

|

| Nearest city | Goliad, Texas |

|---|---|

| Area | 45 acres (18 ha) |

| Built | 1749 |

| NRHP reference No. | 67000024 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | December 24, 1967 |

| Designated NHL | December 24, 1967 |

The Presidio Nuestra Señora de Loreto de la Bahía, often called Presidio La Bahía, is an old fort built by the Spanish Army. It became the center of a town that grew into what is now Goliad, Texas, in the United States. The fort you see today was built in 1747.

During the Texas Revolution, this presidio was very important. It was where the Battle of Goliad happened in October 1835. Later, in March 1836, it was the site of the sad Goliad massacre.

The presidio was carefully rebuilt in the 1960s. In 1967, it was named a National Historic Landmark. While other historical sites in Goliad are now state parks, La Bahía is owned by the Catholic Diocese of Victoria, Texas. It is open to the public as a museum. It is one of the most important old Spanish missions still standing in Texas.

Contents

A Look at Presidio La Bahía's History

The presidio was first built in 1721. It stood on the ruins of a failed French fort called Fort Saint Louis. In 1726, the presidio moved to a new spot on the Guadalupe River. Then, in 1747, the presidio and its nearby mission moved to their current location on the San Antonio River.

By 1771, the fort was rebuilt with strong stone walls. It became "the only Spanish fortress for the entire Gulf Coast" from the Rio Grande to the Mississippi River. A town, later named Goliad, grew up around the presidio in the late 1700s. This area was one of the three most important places in Spanish Texas.

Battles for Control

During the Mexican War of Independence, the presidio was captured twice by rebels. The Republican Army of the North took it in 1813. Then, the Long Expedition captured it in 1821. Each time, Spanish soldiers later defeated the rebels and took the fort back. By the end of 1821, Texas became part of the new country of Mexico. La Bahía was one of two main military bases in Mexican Texas. It was located between San Antonio de Béxar (the main political city) and Copano, a big port.

In October 1835, the Texas Revolution began. A group of Texian fighters marched to La Bahía. After a short 30-minute battle, the Mexican soldiers gave up. The Texians took control of the presidio and renamed it Fort Defiance.

The Alamo and the Goliad Massacre

During the siege of the Alamo, the Texian commander William B. Travis asked for help from La Bahía. He sent messages to James Fannin, who was in charge of the fort. Fannin and his men tried to go help, but they turned back the next day. After the Alamo fell, General Sam Houston told Fannin to leave La Bahía. Fannin and his men left on March 19, 1836. But they moved slowly.

After the Battle of Coleto, Fannin's soldiers were captured and brought back to the Presidio. On March 27, 1836, the Texian prisoners were marched outside the fort walls. Mexican soldiers then executed them. This terrible event is known as the Goliad massacre.

Today, Presidio La Bahía is a restored historical site. Many people think it is one of the best Spanish forts still standing in the United States. Right next to it is the Fannin Memorial Monument. This monument remembers the Goliad massacre.

How the Presidio Began

Spain said it controlled the land we now call Texas. But in the late 1600s, Spain didn't pay much attention to the area between Mexico and Florida. This area was part of New Spain. France saw this and in 1685, Robert de La Salle started a French colony in northern New Spain. La Salle wanted to build his colony near the Mississippi River. But bad maps led his group to the west shore of Matagorda Bay in Spanish Texas.

Spain thought the French colony was a danger to its silver mines and shipping routes. King Carlos II's Council of War said Spain needed to act fast. After searching for several years, a Spanish group led by Alonso de León found the French Fort Saint Louis in 1689. A few months earlier, Karankawa Indians had destroyed the fort and killed most of the French settlers. The Spanish burned the fort and buried the French cannons.

Alonso de León suggested that Spain build presidios (forts) at the Rio Grande, the Frio River, and the Guadalupe River. But Spain didn't have enough money, so they didn't build any. Because of this, several Spanish missions in East Texas struggled and then failed from 1691 to 1693. Texas was again left without Spanish protection.

French Threat and Spanish Response

In the years that followed, France built settlements in Louisiana. This made Spain worried that France would take over its claimed lands. So, Spain reopened the East Texas missions in 1716. This time, they also sent soldiers to protect them. After some problems with France during a war in 1719-1720, Spain decided to send more soldiers to Texas.

In 1721, the Marquis de San Miguel de Aguayo, who was governor of Texas and Coahuila, founded Presidio La Bahía. It was built on the same spot where La Salle's old French fort had been. In 1722, a mission called Espíritu Santo de Zúñiga (also known as La Bahía) was built nearby. It was for the Coco, Karankawa, and Cujane Native American groups. A group of 99 soldiers was stationed at the Presidio to protect it.

The priests at the mission found it hard to convince the Karankawa people to join mission life. In April 1725, the priests asked for the mission to be moved to a better place. The next year, both the presidio (which kept the name "Presidio La Bahía") and Mission Espíritu Santo moved about 26 miles (42 km) inland. They settled along the Guadalupe River in what is now Victoria County. The presidio and mission stayed there for 23 years.

Building on the San Antonio River

In 1747, the Spanish government sent José de Escandón to check on the northern parts of its North American colonies. Escandón asked La Bahía's captain, Joaquín Prudencio de Orobio y Basterra, to explore South Texas. After reading Orobio's report, Escandón suggested moving La Bahía from the Guadalupe River to the San Antonio River. This way, it could better help other Spanish settlements along the Rio Grande. Both the presidio and the mission likely moved in October 1749. Escandón wanted 25 Mexican families to move near the presidio to start a town, but he couldn't find enough people willing to move.

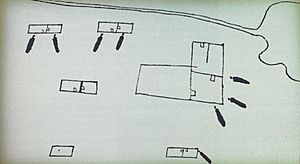

In February 1750, Captain Manuel Ramírez de la Piszena was in charge of the new presidio. Piszena paid for a stone house for himself. The 50 soldiers lived in a large barracks or in one of 40 temporary wooden homes. A chapel was also built for the presidio. The fort had six 8-pound cannons for defense. Soldiers took turns guarding the presidio and the mission. Others guarded the presidio's horses or protected supply wagons coming from the Rio Grande or San Antonio de Béxar. These wagons often faced attacks from Lipan Apache groups.

A Stronghold for Spain

The Seven Years' War ended in 1767. France then gave Louisiana and its claims to Texas to Spain. With France no longer a threat, the Spanish king sent the Marqués de Rubí to inspect all the forts in New Spain's northern frontier. Rubí suggested closing several forts, but he said La Bahía should stay and be rebuilt in stone. La Bahía soon became "the only Spanish fortress for the entire Gulf Coast" from the Rio Grande to the Mississippi River.

The presidio was now at the center of important trade and military routes. It quickly became one of the three most important places in Texas, along with Béxar and Nacogdoches. A town, now called Goliad, soon grew near the presidio. By 1804, this town had one of only two schools in all of Texas.

Texas Fights for Independence

Mexican War of Independence Events

The Mexican War of Independence started in 1810. In late November, the Texas governor, Manuel María de Salcedo, learned that rebel leaders like Miguel Hidalgo planned to invade Texas. On January 2, 1812, Salcedo called troops from all over Texas to Béxar. This left La Bahía with very few soldiers.

Mexican revolutionary Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara had gathered support in the United States. In August 1812, his group, called the Republican Army of the North, invaded Texas. In November, Salcedo led Spanish soldiers to the Guadalupe River to surprise them. But one of Salcedo's soldiers was captured and told the rebels about the plan. The rebel army turned south, avoided the trap, and quickly captured Presidio La Bahía. Salcedo then began to surround the fort. This lasted four months, with small fights happening now and then.

Salcedo couldn't win a clear victory, so he stopped the siege on February 19, 1813. He then moved his troops towards San Antonio de Béxar. The rebels held the presidio until July or August 1813. That's when José Joaquín de Arredondo led royalist (pro-Spain) troops to take back all of Texas. A member of the Republican Army of the North, Henry Perry, tried to recapture La Bahía in 1817. But the presidio had more soldiers from San Antonio, and Perry's men were defeated on June 18 near Coleto Creek.

La Bahía was attacked again in 1821. The United States and Spain signed the Adams-Onís Treaty, which gave all rights to Texas to Spain. Many Americans were upset about this. On October 4, 1821, 52 members of the Long Expedition captured La Bahía. Four days later, Colonel Ignacio Pérez arrived with soldiers from Béxar. Long surrendered. By the end of 1821, Mexico had won its independence from Spain, and Texas became part of the new country.

The Texas Revolution: Battle of Goliad

By 1835, La Bahía was one of two main military bases in Mexican Texas. The other was the Alamo in Béxar. Béxar was the political center, and La Bahía was halfway between it and the important port of Copano. Days after the Texas Revolution started in October 1835, Texian militia members in Matagorda decided to march on La Bahía. They wanted to capture Mexican General Martín Perfecto de Cos. Other Texas settlers joined, bringing the number of Texian volunteers to about 125 men.

The Texians learned that General Cos had already left La Bahía for Béxar. But they kept marching. Several Tejanos (Mexicans living in Texas) who lived near Goliad joined the Texian force. They reported that Colonel Juan López Sandoval had only 50 men, which was not enough to defend the whole fort.

In the early morning of October 10, 1835, the Texians attacked the presidio. They quickly broke through a door on the north wall and ran into the courtyard. Mexican soldiers heard the noise and lined the walls to defend the fort. They opened fire, hitting Samuel McCulloch, a freed slave, in the shoulder. The Texians fired back for about 30 minutes. During a break in the fighting, a Texian shouted that they would "massacre everyone of you, unless you come out immediately and surrender." The Mexican soldiers quickly gave up.

Over the next few days, more Texian settlers joined the group at La Bahía. Stephen F. Austin, the commander of the new Texian Army, ordered 100 men to stay at La Bahía. Philip Dimmitt was put in charge. The rest of the men joined the Texian Army to march on Cos's troops in Béxar. Texian troops took the supplies they found at the fort. They found 300 muskets, but most were broken. The food, clothes, blankets, and other supplies were worth about $10,000. For the next three months, these supplies were given to different companies in the Texian Army. The Texians also took control of several cannons.

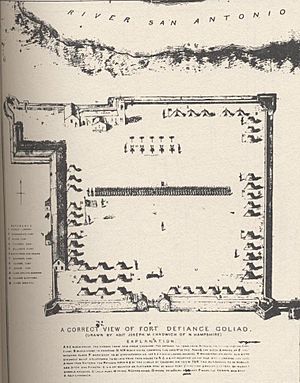

The Alamo's Call for Help

At some point, Colonel James Fannin became the commander of the soldiers at La Bahía. He renamed the presidio Fort Defiance. In February 1836, Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna led a large army into Texas to stop the revolution. Santa Anna and part of his army entered Béxar on February 23 and began to surround the Alamo. The Alamo's commander, William B. Travis, immediately sent a messenger to Fannin. He asked Fannin to send soldiers to help at the Alamo.

Fannin was unsure at first, but he finally decided to go help the Alamo. Some historians believe Fannin's officers convinced him to go. On the morning of February 26, 1836, Fannin set out with 320 men, 4 cannons, and several supply wagons. They had a 90 miles (140 km) march from Goliad to the Alamo. The soldiers at Goliad had no horses to move the wagons and cannons, so they had to use oxen.

Barely 200 yards (180 m) into their trip, one of the wagons broke down. The group stopped for repairs. It then took them six hours to cross the San Antonio River, which was waist-deep. By the time they reached the other side, it was dark, and the men camped by the river. A cold front hit Goliad that evening. The soldiers were not dressed warmly and became "quickly chilled and miserable" in the heavy rain. When they woke up, Fannin realized that all the Texian oxen had wandered off. His men had also forgotten to pack food for the journey. It took most of the day to find the oxen. After two days of travel, Fannin's men had not even gone 1 mile (1.6 km) from their fort.

In a letter, Fannin said his officers asked him to cancel the rescue trip. They had heard that General Urrea's army was marching towards Goliad. However, some men in the expedition said Fannin decided on his own to stop the mission. Many agreed with the decision. One doctor wrote that trying to relieve a fort surrounded by 5,000 men with only 300-400 men, mostly on foot and with little food, was "madness!"

The Goliad Massacre

After learning that the Alamo had fallen, General Sam Houston ordered Fannin and his men to leave La Bahía. They were told to retreat to Victoria. They began their retreat on March 19, 1836. They carried nine cannons but had little food or water. Fannin did not seem to be in a hurry. On the banks of Coleto Creek, Mexican General José de Urrea and his men attacked. The Texians fought back at first, but they soon ran out of water. Fannin then surrendered.

The Texians were taken back to La Bahía, arriving by March 22, 1836. General Urrea asked Santa Anna to treat the prisoners kindly. But on March 27, 1836, the men were marched from the fort and executed by Mexican soldiers. This sad event is known as the Goliad massacre.

Restoring a Piece of History

In the 1960s, a kind person named Kathryn O'Connor gave $1 million to restore the presidio. The rebuilding work happened between 1963 and 1968. Architect Raiford Stripling oversaw the project. The building was mostly rebuilt from the ground up to look exactly as it did originally. One historian called the presidio "one of the finest examples of Spanish ecclesiastical building on the North American continent."

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: La Bahía para niños

In Spanish: La Bahía para niños