Presidio San Luis de las Amarillas facts for kids

|

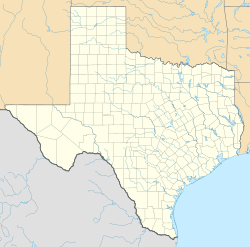

Site of Presidio San Luis de las Amarillas

|

|

Presidio de San Saba in 2013

|

|

| Nearest city | Menard, Texas |

|---|---|

| Area | 15.5 acres (6.3 ha) |

| Built | 1757 |

| NRHP reference No. | 72001369 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | August 25, 1972 |

The Presidio San Luis de las Amarillas, also known as the Presidio of San Sabá, was a Spanish fort built in April 1757. It was located near what is now Menard, Texas, in the United States. This fort was created to protect the Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá, which was started at the same time.

Both the presidio (fort) and the mission were built to help Spain claim this land. They were also part of an agreement with the Lipan Apache people to help each other against shared enemies. The mission was built about three miles away from the fort. The monks wanted this distance so the Spanish soldiers would not influence the Lipan Apaches they were trying to convert to Christianity. Both the first fort and mission were made from logs.

On March 16, 1758, about 2,000 Comanche and Wichita people warriors attacked Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá. These groups were enemies of the Lipan Apache. The presidio sent a small group of soldiers to help, but they were forced back. Two of the three priests at the mission were killed, and the mission was destroyed. However, the Native American warriors did not attack the presidio itself.

More than a year later, 600 men from the presidio went out to find and punish those who attacked the mission. The Spanish force faced heavy losses and had to retreat. After this, the presidio's commander was replaced. The new commander rebuilt the log fort using stone and renamed it Presidio de San Sabá. The fort was left empty in 1768, used again briefly in 1770, and then permanently abandoned.

A part of the presidio was rebuilt in 1936 as a Works Progress Administration project. This was done for the Texas Centennial celebration.

Contents

History of the San Sabá Presidio

Building the Fort

In June 1753, Lieutenant Juan Galván and Father Miguel de Aranda explored the Apache lands. They chose a spot on the San Sabá River for a mission and marked it with a large wooden cross. Later, in December 1754, another group led by Pedro de Rabago y Teran and Father Jose Lopes visited the same area. They named the spot "Paso de la Santa Cruz" and suggested building a strong stone fort there.

On May 18, 1756, the Viceroy (a ruler representing the King) of New Spain, Marques de las Amarillas, ordered Colonel Diego Ortiz Parrilla to move his soldiers from another fort to the San Sabá site. The new fort was named after the Viceroy. Colonel Parrilla was to bring 50 men from his old fort, add 22 from Presidio San Antonio de Béxar, and recruit 27 new soldiers.

On April 5, 1775, Parrilla left some soldiers with supplies and marched with 22 soldiers and 6 priests to the San Sabá site. They arrived on April 17. After more soldiers and supplies arrived, they built the mission and living quarters from logs. They also dug an irrigation ditch. Barracks and family homes were built for the soldiers and their 237 women and children. The mission and the fort were separated by three miles on opposite sides of the river.

In June, about 3,000 Apaches, led by El Chico and Casablanca, passed through. They were on their way to attack the Comanches further north. They did not stay long. Since there were no Native Americans to teach, only one mission was built.

The Attack on the Mission

On February 25, 1758, Native Americans stampeded the presidio's horses, causing the loss of 59 horses. The next day, a group of 6 soldiers was attacked while trying to warn a supply train coming from San Antonio. Colonel Parrilla sent 22 more men to protect the supply train. He also sent 8 soldiers and two cannons to the mission on March 15, after Father Terreros refused to seek safety at the presidio.

Three hours after sunrise on March 16, Joseph Gutierrez arrived at the presidio from the mission. He reported that many Native Americans had arrived and were behaving badly. They were armed with French firearms, pikes, bows, and arrows. Most had muskets and swords. Parrilla then sent Sergeant Flores and four men to help the mission. Flores saw the road filled with hostile Native Americans, and the mission was surrounded by them firing muskets.

Flores's men tried to enter the mission, but the Native Americans formed a line and marched quickly toward the presidio. They fired at the soldiers, wounding three. Flores estimated 1,500 Native Americans were moving to attack the presidio. He then learned that the Texas and Comanche Native Americans had set fire to the mission.

Parrilla held a meeting with his officers. They decided the mission was already destroyed and the presidio was also at risk. They believed any small group sent from the presidio would be easily defeated. Parrilla gathered all 59 of his remaining men (41 were on other duties) and the 237 women and children inside the presidio. At sunset, he sent Flores to check on the mission. Flores found all the mission buildings in flames. However, some people, including Father Miguel Molina, managed to escape because the Native Americans were focused on taking goods.

Lieutenant Juan Galvan's supply train, with 22 soldiers and mule drivers, arrived at the presidio on March 17. The next day, the Native Americans were seen marching north. Eight people were killed, including Fathers Terreros and Santiesteban. Seventeen Native Americans were also killed.

During the summer, a large group of Apaches near the presidio were attacked by northern Native Americans, killing over 50. In December, another 21 Apaches were killed by northern Native Americans, all armed with muskets. On March 30, 1759, Native Americans stole 700 horses, mules, and cattle from the presidio, killing the soldiers guarding them. This left the fort with only 27 horses.

Seeking Revenge

On June 27, 1758, the Viceroy approved a plan to punish the northern tribes. On January 3, 1759, Colonel Parrilla held a special meeting in San Antonio. The governors of Coahuila and Texas, along with frontier officers, suggested a force of 500 men. The Viceroy and King Ferdinand VI approved this plan.

Parrilla's campaign force left in August. It included 50 men from his presidio, 360 more soldiers from other forts, and 176 Native American allies. Among the allies, 134 Apaches served as scouts and guides.

On October 2, Parrilla attacked a Tonkawa village along the Clear Fork Brazos River. Then, on October 7, he attacked a Taovayas (Wichita people) village along the Red River in the Battle of the Twin Villages. The Tonkawas lost 55 killed and 149 taken prisoner. They then led the Spanish to a larger Wichita village in "French country." This village had a strong fence and between 2,000 and 6,000 Wichita and Comanche allies.

Parrilla reported that the enemy felt safe in their fort. They fired from a thick wooded area. Parrilla's two cannons did not have much effect on the fort. By nightfall, he retreated to his camp, leaving the cannons behind. He lost 19 men, 14 were wounded, and 19 were missing. However, he claimed to have killed a main chief and 50 others, wounding many more. Parrilla waited three days before leading an orderly retreat back to the presidio. They arrived on October 25.

After the Attack

In 1760, Joaquin de Montserrat, marques de Cruillas became the new Viceroy. He made Parrilla the governor of Coahuila and put Captain Felipe de Rabago y Teran in charge of the Presidio. Within a year, Rabago rebuilt the fort using strong limestone. He added rooms built into the walls, a blockhouse, and a moat (a ditch filled with water). He also made sure the fort had a full number of well-equipped soldiers. In 1761, Rabago explored the Concho River and sent an expedition west to the Pecos River.

On January 16, 1762, Rabago started Mission San Lorenzo de la Santa Cruz for the Apache Chief Cabezon's tribe. It was located along the El Rio de San Jose (upper Nueces River) and protected by 20 men. Nearby, they also founded Mission Nuestra Senora de la Candelaria for El Turnio's tribe, protected by 10 soldiers. However, in June 1762, northern Native Americans raided the Presidio again, killing 2 soldiers and taking 70 horses.

In 1764, Rabago reported a "severe attack on the Presidio." In 1765, three soldiers were killed in an ambush in a Frio River Canyon. In 1767, Rabago noted that the Comanches had tried to attack the Presidio five times since October 1766. They also tried to attack his supply trains three times.

Official Inspection

King Charles III of Spain sent his Inspector General, Cayetano Pignatelli, 3rd Marquis of Rubi, to tour New Spain in 1766. This was after Spain gained Louisiana in the Seven Years' War. Rubi visited the Presidio in July 1766. He reported that the fort served no real purpose. He said it was as useful as "a ship anchored in mid-Atlantic" for protecting Spain's interests.

Rubi looked at 24 forts along the northern border. He suggested that the Presidio and eight others should be abandoned. He proposed a new border line of forts from San Antonio to Santa Fe, New Mexico to the Gulf of California.

Leaving the Fort

The Comanches stole all the presidio's cattle on December 10, 1767. Native Americans attacked again on January 2, 1768, and stole horses outside the wall on January 14. Then, on February 29, they captured and killed Lieutenant Joaquin Orendain and three other soldiers. The soldiers at the fort then got sick with scurvy. This forced Rabago to leave the Presidio and move to Mission San Lorenzo on June 22.

On April 1, 1769, Captain Manuel Antonio de Oca replaced Rabago as commander. He took the soldiers back to San Sabá but retreated again in early 1770. By June 8, 1771, the governor of Coahuila moved 29 men to San Antonio. On June 21, 1771, the Viceroy ordered the entire group of soldiers to leave and the two missions to be abandoned. In 1772, King Charles III officially ordered the Presidio to be abandoned. This meant leaving East Texas entirely and making San Antonio the new capital of Texas.

San Sabá Silver Mines

In August 1752, five Spaniards from San Antonio started a mine. They found a type of rock called gossan in an area the Apaches had shown them. This area was called Los Almagres. This mining pit was later known as "Boyd's shaft" along Honey Creek, which flows into the Llano River. This area of hills, where gossan is found, is between the old forts of San Sabá and San Antonio de Bexar, in southeastern Llano County.

No valuable ore was found at first. But on November 26, 1755, the governor of Texas, Jacinto de Barrios y Jauregui, sent Bernardo de Miranda y Flores to explore this and another almagre deposit. Miranda kept a journal of his trip from February 17 to March 10, 1756. He reported to the governor on March 29, 1756, and sent a request to the Viceroy on February 15, 1757.

On February 26, Miranda wrote in his journal that his men cleaned out the pit to look for ore veins. He noted a "tremendous stratum of ore" and named the pit San Joseph del Alcazar. In his report, Miranda said, "The mines that are throughout the Cerro del Almagre and all its slope are so abundant." He claimed that ten mining claims had already been filed. He even promised to give a mine to every person in Texas. Miranda reported that he could not travel to another "Almagre Grande" because "many Spaniards would be needed" due to the threat of Comanche Native Americans. In his request to the Viceroy, Miranda mentioned he had "crudely removed some ore, which is what was assayed" (tested).

This three-pound sample of ore and Miranda's report were sent to Manuel de Aldaco in Mexico City. He had the ore tested by smelting (melting) and amalgamation (mixing with mercury). Smelting showed five ounces of silver per hundred pounds of ore, which was too little to be profitable. No silver could be extracted by amalgamation. Aldaco's report asked for thirty cargas (loads) of almagre for more testing.

Miranda asked the Viceroy for these expenses to be paid by the royal treasury. He promised to follow all instructions and make more discoveries. Otherwise, Miranda offered to pay for everything himself if he could be the captain of the soldiers. He noted that a fort with at least thirty men was needed to control the Native Americans.

The commander of the Presidio of San Sabá, Captain Diego Ortiz Parrilla, had seventy-five pounds of ore smelted. This yielded only one and a half ounces of silver. This led him to suggest moving the presidio to Los Almagres in 1757. However, the destruction of Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá by the Comanches in 1758, and more Native American attacks, made the area difficult for the Spanish. The location of the mines was eventually forgotten.

In 1789, five miners working the Los Almagres mines near the Llano River were killed by Lipan Apaches.

Stephen F. Austin's 1827 map showed "Presidio of San Saba." But his 1829 map replaced it with "Silver Mines." Austin's 1831 pamphlet about Texas stated that on the San Sabá River, "traditions say a rich silver mine was successfully wrought many years since, until the Comanche Indians cut off the workmen."

In the 1840s, Ferdinand von Roemer visited the ruins. He noted, "According to legends still told in Texas, the Spaniards were supposed to have worked some rich silver mines here, and the old fort was supposedly erected to protect a mine nearby." He looked for smelting ovens and slag heaps (waste from smelting) but found no traces. He also checked the geology and found it unlikely for silver ore to be in the area's rock formations. However, he thought that other rock types found further downstream might contain ore. On the main entrance of the fort, Roemer found the names: Padilla, 1810; Cos, 1829; Jim Bowie (with his troops), 1829; Moore, 1840.

Comanches and the German Colony

Near the fort was the site of an important meeting. Comanche chiefs, including Buffalo Hump and Santa Anna, met with representatives of the Adelsverein (a German colonization society), including John O. Meusebach. This meeting eventually led to the Meusebach–Comanche Treaty, a peace agreement. As Robert Neighbors and his group traveled through the prairie, they suddenly saw the walls of the old Spanish fort through the mesquite trees.

Gallery

[[Category: Presidio de San Saba website