Battle of Toulon (1744) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Toulon |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Austrian Succession | |||||||

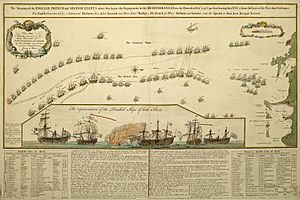

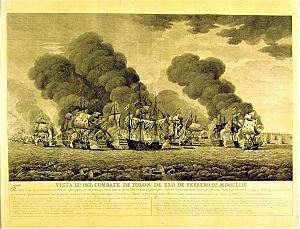

A Spanish illustration of the battle, Naval Museum of Madrid |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 27 ships of the line 3 frigates 3 smaller warships |

30 ships of the line 3 frigates 6 smaller warships |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 149 killed, 467 wounded 3 ships damaged, 1 scuttled |

133 killed, 223 wounded, 17 captured 5 ships damaged, 1 fireship sunk |

||||||

The Battle of Toulon, also known as the Battle of Cape Sicié, was a big naval fight. It happened on February 21-22, 1744, near the French port of Toulon in the Mediterranean Sea. Even though France and Great Britain were not officially at war yet, French ships joined forces with Spanish ships.

The Spanish fleet had been stuck in Toulon for two years. British ships had been blocking them from leaving. The goal of the French and Spanish was to break this blockade. The battle itself was not a clear win for either side at first.

The British commander, Admiral Thomas Mathews, stopped chasing the enemy fleet on February 22. Many of his ships needed repairs. He sailed to Menorca, which meant the British navy lost control of the seas around Italy for a short time. This allowed the Spanish to attack Savoy.

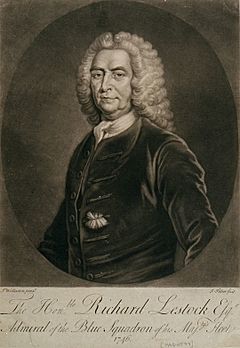

After the battle, Admiral Mathews blamed his second-in-command, Richard Lestock. This led to a big debate in the British Parliament. Mathews was later removed from the navy. Lestock, however, was cleared of all charges. Seven other captains were also removed for not fighting hard enough. This battle led to new rules for naval captains. They were told to be much more aggressive in future fights.

France declared war on Britain soon after the battle. But the battle also caused problems between France and Spain. Spain had more casualties and felt France didn't help enough. The French admiral, Claude Bruyère, was removed from his command. This bad feeling stopped the two countries from working together much more. The Spanish commander, Juan José Navarro, and his ships were later blocked again in Cartagena, Spain.

Why the Battle Happened

The main reason for this battle was a larger conflict called the War of the Austrian Succession. This war started in 1740 when the ruler of Austria, Emperor Charles VI, died. He had no sons, and his daughter, Maria Theresa, was set to inherit. However, some old laws said women couldn't rule.

Other powerful countries like Bavaria, Saxony, and Prussia saw this as a chance to gain power. With help from France, this family problem turned into a huge war across Europe.

Even though French and British soldiers fought each other in 1743, France and Britain were not officially at war. But Spain and Britain had been fighting since 1739 in the War of Jenkins' Ear. This war was mostly in South America, but also in the Mediterranean Sea.

In 1742, a Spanish fleet led by Juan José Navarro took shelter in the French naval base of Toulon. The British Mediterranean Fleet, led by Admiral Thomas Mathews, then blocked them in. The Spanish ships couldn't leave.

In 1743, France and Spain made a secret agreement. They planned to invade Britain. To help with this plan, Navarro was ordered to break out of Toulon. The French fleet, led by Claude Bruyère, was there to help him.

Admiral Thomas Mathews, the British commander, had a difficult relationship with his deputy, Richard Lestock. Both men had asked for Lestock to be moved to a different command, but their requests were ignored. This tension meant Mathews didn't properly discuss his battle plans with Lestock. This lack of communication caused problems later during the battle.

The Battle Begins

On February 21, 1744, the combined French and Spanish fleet sailed out. They had 27 ships of the line (large warships) and 3 frigates (smaller, faster warships). Admiral Mathews and the British fleet chased them. The British ships were generally bigger and had more cannons.

Both fleets used a common battle formation. They lined up their ships in three main groups: the front (vanguard), the middle (centre), and the back (rear). Navarro and the Spanish ships were at the front for their side. The French ships were in the middle. For the British, Mathews led the front, William Rowley led the centre, and Lestock led the rear.

The winds were light, which made it hard to move the ships. The fleets became spread out. Around 11:30 PM on February 21, the ships started to get closer. Mathews signaled his ships to form a "line of battle." This meant lining up the ships one after another to fire their cannons.

But the line wasn't fully formed when night fell. Mathews then signaled his ships to stop. He wanted them to finish forming the line first. The front and middle British groups stopped. However, Lestock, commanding the rear, stopped immediately without forming his line.

By the morning of February 23, the back of the British fleet was far away from the front and middle. Mathews signaled Lestock to speed up. He didn't want to attack with his ships so disorganized. But Lestock was slow to respond. This allowed the French and Spanish fleet to start getting away.

Mathews worried they would escape through the Strait of Gibraltar. He feared they would join another French force planning to invade Britain.

Fighting and Confusion

Knowing he had to attack, Mathews raised the signal to fight. He was on his main ship, HMS Namur. At 1 PM, he left the line to attack the Spanish rear. Captain James Cornewall on HMS Marlborough followed him.

But Mathews left the signal to form the line of battle still flying. So, two different signals were up at the same time. This caused a lot of confusion among the British commanders. Some, like Captain Edward Hawke, followed Mathews. But many others did not. They were either unsure what to do, or like Lestock, they didn't want to cooperate with Mathews.

Namur and Marlborough were heavily outnumbered and didn't have much support. They still managed to fight bravely against the enemy ships. But they were badly damaged. Five more Spanish ships were behind the main action, far away. There was some firing between these ships and the leading ships of the British rear. But most of Lestock's ships in the rear didn't do much during the battle.

The main fight was around Real Felipe, which was Navarro's main ship. Marlborough sailed right through the Spanish line. But it was so badly damaged that it was almost sinking. The Hercules fought off three British ships. The Constante fought against one British ship, then two more, for almost three hours.

The French ships turned around at 5 PM to help the Spanish. Some British commanders thought this was a trick to surround them. The Spanish, still defending themselves, didn't capture the damaged Marlborough. But they did get back the Poder, a ship that had surrendered to the British earlier.

The French and Spanish fleet then continued to escape. It wasn't until February 23 that the British could regroup and chase them again. They caught up with the enemy fleet, which was slowed down by towing damaged ships. The Poder, which couldn't be steered, was left behind and sunk by the French. The British were very close to the enemy fleet. But Mathews again signaled his fleet to stop. The next day, February 24, the French and Spanish fleet was almost out of sight. Mathews returned to port.

What Happened Next

The battle itself didn't have a clear winner. The planned invasion of Britain was called off soon after. But Mathews leaving for Menorca meant the blockade of the Spanish and French army in Italy was lifted. This allowed them to attack.

The battle also caused arguments among the winning side. Philip V of Spain gave Navarro the title "Marquis of Victory." This showed that Spain thought the battle was a success for them, but that the French hadn't done well. He also insisted that the French admiral, de la Bruyère, be removed from command. This bad feeling meant France and Spain didn't work together much in the future. Navarro and his ships were later blocked again in Cartagena, Spain by Rowley, who took over from Mathews.

France declared war on Britain and Hanover in March. Then they invaded the Austrian Netherlands in May. These were big results, supposedly because the British fleet didn't win clearly against a weaker enemy. The British Parliament demanded a public investigation.

At the official naval trial (called a court-martial), seven British captains were removed from the navy. They were found guilty of not doing their "utmost" to fight the enemy, as required by the navy's rules. Two other captains were found innocent, and one died before his trial.

Admiral Mathews was also put on trial. He was accused of bringing the fleet into battle in a messy way. He was also accused of not attacking the enemy when he had a good chance. Everyone agreed he was brave. But he was found guilty of not following the official "Fighting Instructions" about forming a "Line of battle". He was removed from the navy in June 1747.

Even though Lestock ignored his commander's orders, he was found innocent. This was because he followed the exact words of the instructions. He was even promoted to Admiral of the Blue, but he died shortly after.

The public was not happy with these decisions. Many people felt it was unfair that Lestock was pardoned for not fighting, while Mathews was removed for fighting. Lestock's acquittal was largely due to his political connections. Because of problems with political interference in the investigation, Parliament changed the navy's rules in 1749. These changes gave naval courts more power.

They also changed a rule about cowardice or disloyalty in battle. The old rule gave the court a lot of freedom to decide the punishment. The new rule was much stricter. It said that anyone who held back or didn't do their best to fight the enemy would suffer death. This new, stricter wording later led to the famous execution of Admiral Byng in 1757.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Tolón para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Tolón para niños