Chesters Bridge facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Chesters Bridge |

|

|---|---|

| Northumberland, England, UK | |

|

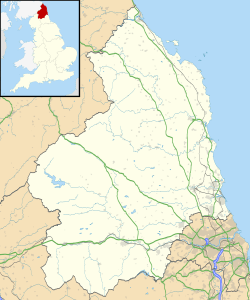

Location in Northumberland

|

|

| Coordinates | 55°01′30″N 2°08′17″W / 55.025°N 2.138°W |

Chesters Bridge was an important Roman bridge in England. It crossed the River North Tyne at Chollerford, Northumberland. This bridge was right next to the Chesters Roman fort. This fort was also known as Cilurnum or Cilurvum.

In 2016, people could no longer visit the bridge parts. This was because of damage from floods.

Contents

History of Chesters Bridge

The remains of the bridge are on the east side of the River North Tyne. You can reach them by walking from near Chollerford Bridge. People first found these remains in 1860. They are some of the biggest stone structures on Hadrian's Wall.

Over time, the River Tyne has moved about 66 feet (20 meters) to the west. This means the river now covers or has washed away much of the west side of the bridge. The eastern part, called an abutment, is still standing tall on the other bank.

Defending the Bridge

The bridge carried a Roman road called the Military Way. This road ran behind Hadrian's Wall. The bridge helped the road cross the River North Tyne.

A cavalry fort was built next to the bridge to protect it. Cavalry means soldiers who fight on horseback. Later, infantry soldiers, who fight on foot, took over the fort. An old stone carving found in 1978 tells us about the first soldiers there. It mentions a brave group of cavalry called ala Augusta.

The First Chesters Bridge

There were actually two bridges built in this spot. The first bridge was not as big as the second one. It was likely built around AD 122-4. This was when Hadrian's Wall was first being built.

This bridge crossed the river using at least eight stone piers. These piers were shaped like hexagons. They were placed about 13 feet (4 meters) apart. The first pier from the east can still be seen today. It was built into the later bridge's stonework.

The whole bridge was about 200 feet (61 meters) long. The piers were wide enough for a structure about 10 feet (3 meters) wide. This was the same width as the "Broad Wall" in this area. This suggests the bridge carried Hadrian's Wall itself across the river. It likely had small stone arches. The stones were held together very tightly. They used iron clamps set in lead to make them strong.

The Second Chesters Bridge

The second bridge was much larger and more impressive. The new eastern abutment was built much higher than before. It had wide walls on both sides of the bridge.

Huge rectangular stones were used for this abutment. Workers lifted them into place using special holes called lewis holes. These holes helped cranes lift the heavy stones. Long iron ties were also used to hold the stones together. This made the front of the bridge very strong.

From this strong base, an elegant bridge with four arches was built. These arches were supported by three big river piers. Each pier was about 34 feet (10 meters) apart. The total length of this bridge was about 189 feet (58 meters). It was designed to carry a road for carts and people.

Not many of the wedge-shaped stones from the arches (called voussoirs) have been found. However, other stone pieces show that the bridge was made of stone. Some people think the top part of the second bridge might have been made of wood. This second bridge was likely built in the early 3rd century. There is no sign that the bridge was repaired after this time. A unique carving is found on the northern face of the eastern abutment.

Excavations at Chesters

In the early 1800s, Nathaniel Clayton owned Chesters House and its land. He moved tons of earth to cover the last parts of the fort. He wanted to create a smooth grassy slope down to the River Tyne. Before they disappeared, he collected many Roman artifacts. He kept these items in his family.

However, his son, John Clayton, was a famous historian. John removed all his father's work. He uncovered the fort again and started digging. He also set up a small museum for the things he found. John Clayton also dug at other Roman sites. These included Housesteads Fort, Carrawburgh Mithraic Temple, and Carvoran.