Chicago Air Shower Array facts for kids

| Location(s) | Utah |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°12′N 112°48′W / 40.2°N 112.8°W |

| Organization | University of Chicago |

| Altitude | 1450 m |

| Wavelength | Ultra high energy (E> 100 TeV) |

| Built | 1988-1991 |

| Collecting area | 235,000 square-meters |

The Chicago Air Shower Array (CASA) was a very important science experiment. It ran in the 1990s and studied super high-energy particles from space. CASA was a huge setup of special detectors. These detectors were located in Utah, USA, at the Dugway Proving Grounds. This area is about 80 kilometers southwest of Salt Lake City.

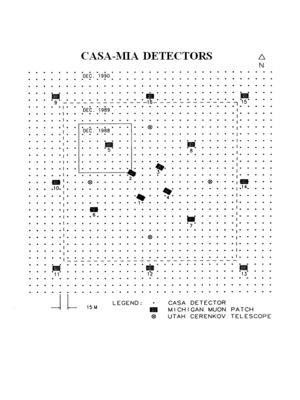

The full CASA detector started working in 1992. It had 1089 detectors. It worked together with another instrument called the Michigan Muon Array (MIA). Together, they were known as CASA-MIA. MIA had 2500 square meters of buried muon detectors.

When it was running, CASA-MIA was the best experiment of its kind. It studied how gamma rays and cosmic rays interact. These interactions happen at energies above 100 TeV (which is 1014 electronvolts). Scientists used data from CASA-MIA for many physics questions. They looked for gamma rays from sources in our Milky Way galaxy. These included the Crab Nebula and X-ray binary stars like Cygnus X-3 and Hercules X-1. They also searched for gamma rays from outside our galaxy. These came from active galaxies and gamma-ray bursts.

CASA-MIA also studied how cosmic rays are made up. It worked with other experiments at the same site. These included BLANCA, DICE, and the Fly's Eye HiRes prototype. CASA-MIA operated non-stop from 1992 to 1999. It was then taken apart in the summer of 1999.

Contents

How CASA-MIA Worked

CASA was built to find super high energy (UHE) gamma rays. These are gamma rays with energies above 100 TeV. When these gamma rays hit Earth's atmosphere, they create a huge "air shower." This shower of particles travels down to the ground.

At the ground, the shower mostly has electrons, positrons, and low-energy gamma rays. It also has muons and some other particles. The shower usually spreads out over 50–100 meters. An air shower array like CASA uses many particle detectors. These detectors are spread out on the ground. They record the particles from the shower.

Scientists figure out where the original particle came from. They do this by looking at when the shower hits each detector. They estimate the particle's energy. This is done by counting how many particles each detector records. They also look at how the particles are spread out.

Before CASA, most air shower arrays were smaller. They usually had 50-100 detectors. They covered about 50,000 square meters. CASA was designed to be much bigger and more sensitive. It used advanced electronics. It was also connected to MIA, a large array of muon detectors.

Scientists expected that gamma ray showers would have fewer muons. Cosmic ray showers, on the other hand, would have many more. This difference helped them tell the two types of showers apart. The original plan was for 1064 detectors. But the number was later increased to 1089.

Key Features of CASA-MIA

- CASA had 1089 scintillation detectors.

- They were arranged in a 33x33 square grid.

- Each detector was 15 meters apart.

- The total area covered was 230,000 square meters.

- Each CASA detector had four separate scintillation counters.

- Each counter was a piece of plastic that glowed when particles hit it.

- A special light sensor called a photomultiplier tube (PMT) read the glow.

- Each CASA detector had its own electronics. This allowed it to collect data on its own.

- The detectors were connected to a central computer. They used special cables for communication.

- The MIA muon array had 1024 scintillation counters.

- Each muon counter was 1.9 m by 1.3 m in size.

- These counters were buried 3 meters underground.

- Signals from MIA counters went to a central trailer. There, their arrival times were measured.

CASA-MIA performed very well. It was a leading air shower experiment for many years. Only in the late 2010s did new experiments become more sensitive. These include the Tibet Air Shower Array and the High Altitude Water Cherenkov Experiment.

For gamma rays coming from directly overhead, the average energy detected was 115 TeV. The accuracy of finding the gamma ray's direction was very good. It was about 0.7 degrees for average showers. For higher energy showers, it improved to 0.25 degrees. The muon array was very important. It helped remove background noise from cosmic ray events. For every 17 cosmic ray events, only one was mistakenly counted as a gamma ray. This rejection power got even better at higher energies.

History of the Project

The idea for CASA came from exciting results in the 1980s. Several experiments reported extra air shower events. These events seemed to come from two X-ray binary stars: Cygnus X-3 and Hercules X-1. In 1983, experiments in Kiel and Haverah Park reported extra events from Cygnus X-3. The timing of these events seemed to match the star's 4.8-hour orbit.

These signals were not very strong. But they suggested that Cygnus X-3 was sending out huge amounts of super high-energy gamma rays. This would mean it was very good at speeding up cosmic rays. It could even be a major source of cosmic rays in our galaxy.

After these findings, many science groups started building new air shower arrays. They wanted to check these results. One of these groups was from the University of Chicago. It was led by James W. Cronin. Cronin wanted to build a definite experiment. It would either prove or disprove the Cygnus X-3 results.

His experiment would be much larger and more sensitive. It would also use a big array of muon detectors. These detectors would help remove background noise from cosmic rays. Showers from gamma rays are expected to have far fewer muons than those from cosmic rays. Cronin gathered a team of scientists to build CASA. The University of Chicago group worked with teams from the University of Michigan and the University of Utah. These universities had already built a muon array and a smaller air shower array. The chosen site for CASA was Dugway Proving Grounds.

Construction of CASA happened between 1988 and 1991. The work was done at the University of Chicago. Completed detectors were shipped to Utah. Students, postdocs, and professors installed them. A small array of 49 detectors started working in 1989. A larger 529-detector array followed in 1990. The full 1089-detector CASA array began normal science operations in December 1991. It worked with the 1024-counter muon array.

CASA ran very successfully until 1997. During that time, it recorded about 3 billion air shower events. It continued to operate partly for several more years. It worked with the BLANCA and DICE experiments. All experiments at the site, including CASA, stopped working in 1999.

What CASA-MIA Discovered

The scientific results from CASA-MIA were published in many papers. They covered three main areas of high-energy astrophysics. These were gamma-ray point sources, diffuse gamma-ray sources, and cosmic ray physics.

Gamma-Ray Point Sources

CASA-MIA set very strict limits on gamma ray emissions. It looked at all sources reported by earlier experiments. These included Cygnus X-3, Hercules X-1, the Crab Nebula, and active galaxies. For these sources, CASA-MIA's limits were much lower. They were typically 100 to 1000 times lower than previous measurements. Scientists also searched for sudden bursts or regular emissions from these sources. They also did a general survey of the sky above the array.

Diffuse Gamma-Ray Sources

The large muon array helped CASA-MIA study diffuse gamma-ray sources. These are gamma rays spread out across the sky. The most important result came from searching for diffuse emission that was the same in all directions. This search set a limit on how much of the highest energy cosmic rays are electromagnetic. Another important finding came from studying diffuse emission from the Galactic plane. A separate study looked for bursts from anywhere in the sky. This helped scientists understand short cosmic events. An example is the explosion of primordial black holes.

Cosmic Ray Physics

CASA-MIA was great at measuring properties of super high-energy cosmic rays. It had a large, uniform air shower array and a big muon detector. It measured the number of electrons and muons in air showers. This helped measure the cosmic ray energy spectrum. This spectrum shows how many cosmic rays there are at different energies. CASA-MIA found a smooth change in the spectrum. This was different from some earlier experiments. Those experiments reported a sharper change, known as the "knee."

CASA-MIA also measured the makeup of cosmic rays. It found a mix of different particles at lower energies (below 1,000 TeV). This mix smoothly changed to heavier particles at energies near 10,000 TeV. The BLANCA instrument also measured cosmic ray makeup. It worked with CASA-MIA and used a different method.

Who Worked on CASA

The CASA project was first thought of by James W. Cronin. A team of scientists, engineers, and technicians built it. They were from the Enrico Fermi Institute at the University of Chicago. The first group of scientists included Cronin, Kenneth Gibbs, Brian Newport, Rene Ong, and Leslie Rosenberg. It also included students Nicholas Mascarenhas, Hans Krimm, and Timothy McKay.

During CASA's operation, the Chicago group grew. It included Mark Chantell, Corbin Covault, Brian Fick, Lucy Fortson, Kevin Green, Alexander Borione, Joseph Fowler, and Scott Oser. The Michigan Muon Array (MIA) was built by a team from the University of Michigan. This team included James Matthews, David Nitz, Daniel Sinclair, and John van der Velde. It also included Kevin Green, Mike Catanese, and Ande Kennedy Glasmacher.

See Also

- Large High Altitude Air Shower Observatory

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |