Chicago Woman's Club facts for kids

The Chicago Woman's Club was a special group formed in Chicago in 1876. Women started it because they wanted to learn more and help improve their community. This club was famous for creating many learning chances in Chicago. They even helped start the first ever juvenile court in the United States, which is a court just for young people.

The club was mostly made up of women from different backgrounds, including doctors, lawyers, and teachers. They often worked to make social and educational changes in Chicago. They also invited important women, like artists and those who supported women's right to vote, to give talks.

The Chicago Woman's Club also created the first Protective Agency in the United States. This agency helped women and children who needed protection. The group worked to improve hospitals for people with mental health needs and other health services. They also helped set up the first kindergartens and nursery schools in Chicago. Later, the club became involved in the movement for women's right to vote.

The club continued its work until 1999, when it closed down. The money and resources from the club were then used to help students with scholarships and support other good causes.

Contents

The Chicago Woman's Club: A Look Back

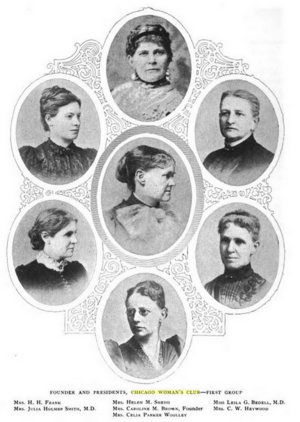

The Chicago Woman's Club officially began on May 17, 1876. In 1885, it became an official organization. Caroline Brown was the founder. She suggested to her friends that they form a group to socialize and work together. By 1877, the club had about thirty members. Many of these women were active in making social changes, writing, and helping others.

The club offered advanced learning opportunities that were as challenging as college courses. At that time, this was one of the few ways many women could continue their education after school. The Chicago Woman's Club had six main committees: Reform, Philanthropy, Home, Education, Art and Literature, and Philosophy and Science. Every member had to join at least one committee. Joining the club was special, and new members needed to be invited by existing ones.

The club first met at Caroline Brown's house. Later, they rented rooms and met in different places like the Palmer House. In 1929, the club moved into a new, six-story building on Michigan Avenue. This building was designed by famous architects and is now part of Columbia College. The club grew from 30 members in 1877 to 1,200 members by 1921. Each year, the club published a large yearbook to share their activities. Their motto was "Humani nihil a me alienum puto", which means "I consider nothing human alien to me." On May 25, 1892, they chose ivory white and gold as their official colors.

In 1876, the club welcomed its first Jewish members, Henriette and Hannah Solomon. The first African American member was Fannie Barrier Williams. Her membership faced challenges, but in 1895, the club voted not to exclude anyone based on race. She officially became a member in 1896. In 1894, a club for African American women was started, inspired by the Chicago Woman's Club.

Helping the Community

The Chicago Woman's Club became very active in social improvements around the 1880s. Members were concerned about families facing difficult working conditions and children who had to work to support their families. They held monthly meetings to study laws that affected women and children.

The club helped improve the Cook County Mental Health Hospital. They supported women becoming assistant doctors there and worked to ensure better care for women staying at the hospital. They visited the hospital often and reported any problems. In 1886, they even suggested changes to laws for the care of patients.

The Chicago Woman's Club also pushed for a general hospital to treat people with infectious diseases. They worked for many years to make this happen. The club also helped create a Children's Hospital Society of Chicago. In 1909, they suggested ways to improve medical staff at the county jail.

The club was involved in other health issues too. They promoted public messages against spitting in Chicago and supported laws against cigarettes. In 1930, they gave money to support a campaign for cancer awareness and education.

The club helped appoint a night matron at the jail in 1884. This matron would look after women and children held there. Club members Ellen Henrotin and Sara Hackett Stevenson were key in creating the Protective Agency for Women and Children in 1886. This was the first agency in the country to help wives who had been harmed or treated unfairly. The club offered legal help to women and provided lawyers to those who couldn't afford them. They often supported those who needed help in court. In 1897, the Protective Agency joined with the Bureau of Justice. The women made sure they still had control over cases involving women and children. In 1905, the agency joined the Legal Aid Society of Chicago. Also in 1905, the club asked the state of Illinois to change laws to better protect children.

Important club members like Julia Lathrop, Jane Addams, and Lucy Flower helped create the Illinois Juvenile Court Law in 1899. This law established the first juvenile court in the country. The club even helped pay the salaries of the probation officers who worked in this new court. Before this, young people were often treated unfairly and held with adults in jails. In 1929, the Chicago Woman's Club and other groups funded a study about behavior challenges in young boys.

The Chicago Woman's Club was also a part of the woman's suffrage movement. In 1894, they formed the Chicago Political Equality League. This group worked to show that supporting women's right to vote was a good thing. The club also hosted talks about suffrage and invited famous suffragists, like Susan B. Anthony, to speak.

Environmental concerns were important to the club too. Members spoke out against killing wild birds for their feathers, which were used in women's fashion. In 1905, they supported efforts to protect natural areas in Illinois.

Supporting Education

The Chicago Woman's Club worked on many educational projects. Some of these, like asking for children's schooling in prisons, were connected to their other community improvement efforts. In 1887, the club asked Mayor Roche to appoint women to the Board of Education in Chicago. Later, in 1890, they nominated five women for the school board. Ada Celeste Sweet was appointed in 1892, and the club pushed for her appointment to be approved. In 1898, the club cleaned a school from top to bottom to show what a clean and healthy school building should look like. In 1916, they urged the school board to choose teachers based only on their teaching skills. Club member Lucy Flower successfully worked for Illinois to have a law requiring children to attend school.

The Chicago Woman's Club also helped set up the first public nursery school in the United States, working with the Chicago Board of Education. The club was also the first to provide money for a kindergarten in public schools. In 1905, the club created a special fund for the John H. Hamline school to support parent and children's clubs.

The club also supported education for people with visual impairments beyond public schools. In 1906, members taught visually impaired people in their homes. They taught Braille, shorthand, typewriting, and weaving. This work grew so much that more money was needed, and a bill was introduced to provide funds for these teachers.

In 1889, the club "adopted" Norwood Park School. They donated money and asked for more funds for the school. This school was both an orphanage for over 300 homeless boys and a training school. The club also helped the School Children's Aid Society by giving their time and new clothes to poor students so they could attend school. They also started a school for boys staying at the Chicago common jail. In 1898, the Chicago Woman's Club made sure boys in the county jail had a Thanksgiving dinner.

In 1885, the club started a training school for household workers. They continued this work by creating a school, offering scholarships, providing housing for students, and setting up an employment agency. In 1900, the club also suggested that boys should learn how to cook in public schools. The idea was also to teach boys other home skills, so they would be helpful at home when they grew up. The Chicago Woman's Club also started vocational classes with scholarships for interested students.

In 1892, the club helped pay for women's dormitories at the University of Chicago. In 1897, the Chicago Woman's Club helped raise money to add to the Egyptian collection at the University of Chicago.

In 1898, the club created an information center for students. It provided resources and information for a small fee. The club kept records of the questions asked and encouraged only serious inquiries.

Improving Working Conditions

Besides working on community improvements and education, the club also supported worker's rights. During the World's Colombian Exposition, the Chicago Woman's Club asked event planners to keep the exposition open on Sundays. This would allow working people to visit. The club also supported conferences like "Women in Modern Industrialism," which shared information about women in different jobs.

In 1894, the club helped find 200 jobs for women and girls. Later, the club started the Women's Emergency Association, which helped about 1,500 people find work. This organization was praised for helping to improve laws for working women and children in Illinois. The Chicago Woman's Club also created an Employment Bureau.

The club worked with the Women's Trade Union and helped boycott factories where working conditions were bad. The club voted to send representatives to speak for clerks who were overworked in stores. They also pushed for half-holidays for these workers. In 1912, the club formed a committee to look into women's working conditions in factories. Their goal was to create a minimum wage for working women.

Important Members of the Club

Many important women were members of the Chicago Woman's Club. Physician Sara Hackett Stevenson was president from 1892 to 1894. Ada Celeste Sweet was elected president in 1894. Other presidents included novelist and preacher Celia Parker Woolley, reformer Lucy Flower, Lydia Avery Coonley, and Julia Holmes Smith. Many of the club's presidents were also members of the Fortnightly Club.

- Jane Addams

- Anna Blount

- Louise DeKoven Bowen

- Myra Bradwell

- Lydia Avery Coonley

- Lucy Flower

- Ellen Martin Henrotin

- Mary Emma Holmes

- Mary Lewis Langworthy

- Julia Lathrop

- Emma Gilson Wallace

- Lena B. Mathes

- Catharine Waugh McCulloch

- Mary McDowell

- Anna E. Nicholes

- Bertha Palmer

- Elia Peattie

- Julia Holmes Smith

- Hanna G. Solomon

- Sara Hackett Stevenson

- Ada Celeste Sweet

- Alice Bradford Wiles

- Frances Willard

- Fannie Barrier Williams

- Celia Parker Woolley

- Rachelle Yarros

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |