1973 Chilean coup d'état facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 1973 Chilean coup d'état |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War in South America | |||||||||

|

From top to bottom: the bombing of La Moneda on September 11, 1973, by the Chilean Armed Forces; a journalist and soldiers during the coup; and detainees being detained at the National Stadium

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Other working-class militants |

Supported by: |

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Political support | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 46 GAP | |||||||||

| 60 in total during the coup | |||||||||

The 1973 Chilean coup d'état was a sudden takeover of the government in Chile by the military. It happened on September 11, 1973. The military overthrew the government of President Salvador Allende. He was a democratic socialist leader. Allende was the first Marxist (someone who believes in a society where everyone is equal and shares wealth) to be elected president in a Latin American democracy.

Allende faced many problems during his time as president. There was social unrest and political tension with the National Congress of Chile. The United States, led by President Richard Nixon, also tried to harm Chile's economy. On September 11, 1973, military officers, led by General Augusto Pinochet, took control. This ended civilian rule in Chile. Later, the CIA admitted its role in trying to stop Allende from becoming president in 1970. Documents from 2023 showed that Nixon and Henry Kissinger knew about the coup plans.

After the coup, a military government called a military junta was formed. It stopped all political activities in Chile. It also suppressed left-wing groups like communist and socialist parties. Pinochet quickly became the most powerful leader. He was officially declared president of Chile in late 1974. The Nixon government quickly recognized the new military government. It also helped Pinochet stay in power.

During the attacks, Allende gave his last speech. He said he would stay at the Palacio del La Moneda, the presidential palace. He refused to leave the country. He died in the palace, but how he died is still debated.

Before the coup, Chile was known for its democracy in South America. Other countries in the region often had military rulers. The coup ended a long period of democratic governments in Chile. Historian Peter Winn called the 1973 coup one of the most violent events in Chilean history. It led to a period of serious human rights issues under Pinochet. He started a harsh campaign against people who opposed him. This greatly weakened groups on the left. Chile later returned to democracy peacefully in 1989. Because it happened on September 11, like the 2001 attacks in the U.S., it is sometimes called "the other 9/11."

Contents

How the Coup Happened

Allende's Election and Challenges

Salvador Allende ran for president in 1970. He was against Jorge Alessandri and Radomiro Tomic. Allende won the most votes, but not a clear majority. So, the National Congress of Chile had to choose the president.

The Chilean Constitution of 1925 did not allow a president to serve two terms in a row. The current president, Eduardo Frei Montalva, could not run again. The U.S. CIA had a plan to get Congress to choose Alessandri. He would then resign, allowing Frei to run again. Allende promised to follow the constitution to gain support. Congress then chose Allende as president.

The U.S. government was worried about a "socialist experiment" in Chile. It put pressure on Chile's elected government. This included diplomatic, economic, and secret actions. In 1971, Fidel Castro, the leader of Cuba, visited Chile. This worried American officials even more.

In 1972, the economy faced problems. Prices went up very fast, by 140 percent. This led to a black market where goods were sold illegally. In October 1972, many strikes happened in Chile. Small business owners, unions, and student groups joined. They hoped to remove the elected government. The strikes hurt the economy. They also led to General Carlos Prats, the Army head, joining the government. He replaced General René Schneider, who had been killed in 1970. General Prats supported the idea that the military should not get involved in politics.

Despite the struggling economy, Allende's Popular Unity group gained more votes in the March 1973 elections. But the alliance between Popular Unity and the Christian Democrats ended. The Christian Democrats joined with the National Party. These two parties formed the Confederation of Democracy (CODE). This conflict between the government and Congress made it hard to govern.

Allende worried that his opponents were planning to kill him. He sent a message to Fidel Castro. Castro gave him advice: keep skilled workers in Chile, sell copper only for U.S. dollars, avoid extreme actions, and keep good relations with the military. Allende tried to follow this advice. But the last two points were difficult.

The Chilean Military Before the Coup

Before the coup, the Chilean military had stayed out of politics since the 1920s. Most officers were not paid well. They spent time in military clubs, meeting other officers and their families. They often married within military families. In 1969, some military members rebelled in what was called the Tacnazo insurrection. This was a protest about low funding, not a full coup.

In the 1960s, military governments took power in Brazil, Argentina, Peru, and Bolivia. These coups were supported by the U.S. The Chilean military's poor conditions were different from the power gained by militaries in neighboring countries.

The U.S. influenced the Chilean military with anti-communist ideas. This happened through various cooperation programs. One example was the U.S. Army School of the Americas.

Growing Crisis in Chile

On June 29, 1973, Colonel Roberto Souper tried to overthrow Allende. He surrounded the presidential palace with tanks. This failed coup was known as the Tanquetazo. It was organized by a nationalist group called "Fatherland and Liberty".

In August 1973, the Supreme Court complained that the government was not enforcing laws. On August 22, the Christian Democrats and National Party in Congress accused the government of breaking the constitution. They asked the military to restore order.

For months, the government was afraid to call on the Carabineros (national police). They suspected the police were disloyal. On August 9, Allende made General Carlos Prats Minister of Defense. Prats resigned on August 24, after a public protest by his generals' wives. General Augusto Pinochet replaced him as Army commander-in-chief. In late August 1973, many Chilean women protested against the government. They were upset about rising costs and shortages of food and fuel.

Congress Calls for Action

On August 23, 1973, the Chamber of Deputies passed a resolution. It was supported by the Christian Democrats and National Party. The resolution asked the President and military to "immediately end" actions that broke the Constitution. It said the Allende government wanted "absolute power" to create a "totalitarian system." It also accused the government of creating armed groups that could clash with the military.

Some people argued that this resolution was a call for the armed forces to overthrow the government. Pinochet later used this resolution to justify the coup.

Planning the Coup

By mid-July, the Army's high command agreed that Allende's government should end. But they didn't know how. Constitutional generals, led by General Carlos Prats, faced pressure from hardline anti-Allende officers. Prats suggested a government that included Allende and the armed forces. He believed this would stop extreme workers from rebelling. Other generals supported this idea, some wanting it to be a short-term solution.

After Prats resigned on August 24, the hardline group gained power. This group wanted a full military coup. Generals like Pinochet, Sergio Arellano Stark, and Javier Palacios joined this group. Even General Orlando Urbina, who was seen as loyal to Allende, joined the coup plotters.

On September 9, Pinochet met with President Allende. Allende asked him to create an emergency plan in case of a coup. Pinochet promised to have it ready the next day. On the day of the coup, only Admiral Montero of the Navy and General Sepúlveda of the Carabineros remained loyal to the Constitution.

Outside Help for the Coup

United States Involvement

Many people around the world suspected the U.S. was involved. At first, the U.S. denied any role. But a New York Times article led to a U.S. Senate investigation. A 2000 report by the United States Intelligence Community stated:

Although CIA did not instigate the coup that ended Allende's government on 11 September 1973, it was aware of coup-plotting by the military, had ongoing intelligence collection relationships with some plotters, and—because CIA did not discourage the takeover and had sought to instigate a coup in 1970—probably appeared to condone it.

The report also said the CIA supported the military government after the coup. Recordings of calls between Nixon and Henry Kissinger showed they used the CIA to weaken Allende's government. Nixon even said, "our hand doesn't show on this one."

Historian Peter Winn found "extensive evidence" of U.S. involvement. He said their secret support was key to the coup and to Pinochet staying in power. Winn also noted a CIA operation to create false reports of a coup against Allende. This was used to justify military rule. Other authors point to the Defense Intelligence Agency helping with missiles used to bomb the presidential palace.

Documents from the Clinton administration showed U.S. hostility to Allende's election in 1970. CIA agents were sent to Chile to prevent a Marxist government. They spread anti-Allende messages. The CIA tried to bribe the Chilean legislature and influence public opinion. They also funded strikes to force Allende to resign. This was called the "Track I" approach.

Another CIA approach, "Track II," tried to encourage a military coup. It aimed to create a crisis in the country. A CIA telegram from October 16, 1970, stated:

It is firm and continuing policy that Allende be overthrown by a coup. It would be much preferable to have this transpire prior to 24 October but efforts in this regard will continue vigorously beyond this date. We are to continue to generate maximum pressure toward this end utilizing every appropriate resource. It is imperative that these actions be implemented clandestinely and securely so that the USG and American hand be well hidden."

CIA agents told Chilean military officers that the U.S. would support a coup. But they would stop military aid if it didn't happen. The CIA also supported negative propaganda against Allende. This was often spread through the newspaper El Mercurio. Financial help was given to Allende's opponents. This was used to organize strikes and unrest. The U.S. company ITT Corporation owned part of a Chilean telephone company. It also funded El Mercurio. The CIA used ITT to hide where the money for Allende's opponents came from.

United Kingdom Involvement

In September 2020, Declassified UK reported that the UK government also interfered. A secret unit of the Foreign Office started a propaganda campaign in Chile. This was to stop Allende from winning elections in 1964 and 1970.

This unit, the Information Research Department (IRD), gathered information to harm Allende. They shared this information with important people in Chile. The IRD also shared intelligence about left-wing activities with the U.S. government. British officials helped a CIA-funded media group. This was part of a larger U.S. effort to overthrow Allende.

Australia's Role

An Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) office was set up in Chile in July 1971. This was at the CIA's request. The Australian Foreign Minister approved it. The new Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam, learned about it in February 1973. He ordered the operation to close. However, the last ASIS agent did not leave Chile until October 1973, after the coup.

In June 2021, a former intelligence analyst, Clinton Fernandes, tried to confirm Australia's involvement. On September 10, 2021, documents confirmed that Australia did approve the CIA's request. ASIS set up a surveillance unit in Santiago. This was part of the CIA's campaign against Allende.

The Military Action

By 6:00 AM on September 11, 1973, the Navy had taken control of Valparaíso. They placed ships and marines along the coast. They also shut down radio and television networks. President Allende was told about the Navy's actions. He immediately went to the presidential palace, La Moneda, with his bodyguards. By 8:00 AM, the Army had closed most radio and TV stations in Santiago. The Air Force bombed the remaining active stations. Allende received incomplete information. He thought only a small part of the Navy was against him.

President Allende could not reach military leaders. Admiral Montero, a loyal Navy commander, could not be reached. His phone was cut, and his cars were damaged before the coup. Leadership of the Navy went to José Toribio Merino, a coup planner. Augusto Pinochet, Army General, and Gustavo Leigh, Air Force General, did not answer Allende's calls. The head of the uniformed police, José María Sepúlveda, and the head of detectives, Alfredo Joignant, answered Allende's calls. They went to the palace. When Defense Minister Orlando Letelier arrived at the Ministry of Defense, he was arrested.

Allende still hoped some military units were loyal. He believed Pinochet was loyal. But at 8:30 AM, the armed forces announced they controlled Chile. They said Allende was removed from power. Only then did Allende understand the full scale of the rebellion. Despite having no military support, Allende refused to resign.

Around 9:00 AM, the police at La Moneda left the building. By 9:00 AM, the armed forces controlled most of Chile. Only the city center of Santiago was not under their control. Allende refused to surrender. The military said they would bomb the palace if he resisted. Allende refused to leave. He wanted to bring about change peacefully. The military tried to negotiate, but Allende refused to resign. He said it was his duty to stay in office. Finally, at 10:30 AM, Allende gave a farewell speech. He told the nation about the coup and his refusal to resign.

General Leigh ordered the presidential palace bombed. Air Force jets arrived to bomb the palace. The defenders did not surrender until almost 2:30 PM. Initial reports said the 65-year-old president died fighting. Later, police said he had killed himself.

People Affected by the Coup

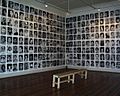

In the first months after the coup, the military arrested many people. Thousands of Chilean leftists, or those suspected of being so, were killed or went missing.

About 130,000 people were arrested in three years. Thousands died or disappeared in the first months of the military government.

What Happened Next

A New Government Takes Over

On September 13, the military government dissolved Congress. They outlawed parties that were part of Allende's Popular Unity group. All political activity was stopped. The military took control of all media, including radio. It is not known how many Chileans heard Allende's last speech live. But a copy of the speech survived. The military used the media as their "propaganda machine." Only two newspapers, El Mercurio and La Tercera de la Hora, were allowed to publish. Both were against Allende. The military government stopped any speech that resisted their rule.

After the coup, the military government published a book. It was called El Libro Blanco del cambio de gobierno en Chile (The White Book of the Change of Government in Chile). They tried to justify the coup. They claimed Allende's government was planning its own coup, called Plan Zeta. Historian Peter Winn said the Central Intelligence Agency helped create this false story. They also helped spread it to the press. Even though it was later proven false, some still point to similarities with other plans.

A document from September 13 showed that Jaime Guzmán was already working on a new constitution. One of the first things the new government did was create a National Youth Office. This was to get support from young people for the new government.

Global Reactions

Juan Domingo Perón, the President of Argentina, condemned the coup. He called it a "fatality for the continent." Argentine students protested the coup at the Chilean embassy. They chanted that they were "ready to cross the Andes."

Remembering the Coup

People remember the coup in different ways. There are different ideas about why it happened and what its effects were. Both those who opposed and supported the coup have their own ways of remembering it.

On September 11, 1975, Pinochet lit the Llama de la Libertad (Flame of Liberty) to remember the coup. This flame was put out in 2004. A street in Santiago was renamed Avenida 11 de Septiembre in 1980. For the 30th anniversary of the coup, President Ricardo Lagos reopened the Morandé 80 entrance to La Moneda. This entrance had been removed during repairs after the bombing.

Films and Documentaries About the Coup

Many films and documentaries have been made about the coup:

- Bear Story

- Bestia

- Chicago Boys

- Colonia

- Ecos del Desierto

- Invisible Heroes

- Machuca

- Missing (1982 film)

- ¡Nae pasaran!

- No

- ReMastered: Massacre at the Stadium

- The Battle of Chile

- The Black Pimpernel

- The House of the Spirits

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Golpe de Estado en Chile de 1973 para niños

In Spanish: Golpe de Estado en Chile de 1973 para niños