Coal strike of 1902 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Coal strike of 1902(Anthracite coal strike) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

John Mitchell, President of the UMWA, arriving in Shenandoah surrounded by a crowd of breaker boys.

|

|||

| Date | May 12 – October 23, 1902 | ||

| Location | |||

| Goals | Eight-hour workday, higher wages, and union recognition |

||

| Methods | Striking | ||

| Resulted in | Nine-hour workday (reduced from ten) wage increase of 10% first strike settled by federal arbitration |

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

| Number | |||

|

|||

| Settlement arbitrated by Theodore Roosevelt's administration |

|||

The Coal strike of 1902 was a big strike by coal miners in eastern Pennsylvania. These miners worked in the anthracite coal fields. They were part of a group called the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA).

The miners went on strike because they wanted better pay and shorter workdays. They also wanted their union to be officially recognized. This strike was a big deal because it threatened to stop the supply of coal. In those days, many homes in American cities used coal for heating. Anthracite coal was especially important because it burned hotter and cleaner.

The strike ended with the miners getting a 10 percent raise. Their workday was also shortened from ten hours to nine. The coal owners got to charge more for coal. However, they still did not officially recognize the union. This strike was special because it was the first time the U.S. federal government stepped in. President Theodore Roosevelt helped settle the dispute as a neutral helper.

Contents

- Why Did Miners Strike for Better Conditions?

- What Caused the Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902?

- How Did President Roosevelt Intervene?

- How Did J.P. Morgan Help End the Strike?

- What Was the Anthracite Coal Strike Commission?

- What Happened After the Strike?

- Images for kids

- More to Explore

- Music About the Strike

Why Did Miners Strike for Better Conditions?

The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) had already won a big victory in 1897. That strike involved soft-coal miners in the Midwest. The union gained many new members after that success. From 1899 to 1901, there were smaller strikes in the anthracite coal areas. These strikes helped the union learn more and get more workers to join.

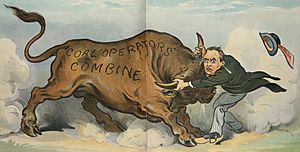

In 1899, a strike in Nanticoke showed that unions could win. Even against large railroad companies, they could make a difference. The UMWA hoped to achieve similar gains in 1900. But the coal owners were much tougher this time. They had formed a powerful group that controlled most of the anthracite coal.

The owners refused to talk with the union or let anyone help settle the dispute. So, the union went on strike on September 17, 1900. Many miners from different backgrounds joined the strike. This surprised even the union leaders.

A politician named Mark Hanna tried to help solve the strike. He was a Republican Senator and owned coal mines himself. The strike was happening just before a big presidential election. Hanna worried it would hurt the chances of President William McKinley getting re-elected. He convinced the owners to give the miners a raise and a way to complain about problems. However, the owners still refused to officially recognize the UMWA. The union still called it a victory and dropped their demand for recognition that time.

What Caused the Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902?

The same problems that led to the 1900 strike were still there in 1902. The union still wanted to be recognized. They also wanted some say in how the coal industry was run. The coal owners were still upset about the deals they made in 1900. They did not want the government to get involved at all.

About 150,000 miners needed their weekly pay. Millions of people in cities needed coal to heat their homes. John Mitchell, the President of the UMWA, suggested a peaceful solution. He wanted a group called the National Civic Federation to help. This group was made up of employers who believed in talking things out with workers.

Mitchell also suggested that a group of respected religious leaders look into the conditions in the coal mines. But George Frederick Baer, who was in charge of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, refused both ideas. He said that mining was a business, not a religious or emotional matter. He felt he couldn't let others manage his business.

On May 12, 1902, the anthracite miners voted to go on strike. They were in Scranton, Pennsylvania. On June 2, even the maintenance workers, who had safer jobs, joined the strike. About 80 percent of the workers, over 100,000 people, supported the union. Some 30,000 miners left the area to find work elsewhere. About 10,000 even went back to Europe.

The strike soon led to threats of violence. There were clashes between strikers and those who tried to keep working. The Pennsylvania National Guard, local police, and hired detectives were also involved.

How Did President Roosevelt Intervene?

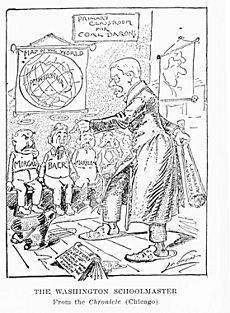

On June 8, President Theodore Roosevelt asked his Commissioner of Labor, Carroll D. Wright, to look into the strike. Wright suggested some changes. He thought a nine-hour workday could be tried. He also suggested some limited collective bargaining, where the union could talk with the owners. Roosevelt decided not to share this report. He didn't want to seem like he was taking the union's side.

The coal owners still refused to talk with the union. George Baer wrote a letter saying that God had given control of property to "Christian men." He said these men would protect the rights of workers, not "labor agitators." The union used this letter to get public support for their side.

Roosevelt wanted to help, but his Attorney General, Philander Knox, said he didn't have the power to step in. Many Republicans were worried about the strike lasting into winter. People would need coal to stay warm. Roosevelt said that a "coal famine" in winter would cause "terrible suffering."

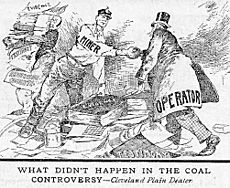

Roosevelt called a meeting on October 3, 1902. Representatives from the government, the union, and the owners were there. The union saw the meeting itself as a step toward being recognized. They spoke in a friendly way. But the owners told Roosevelt that strikers had caused violence. They said he should use the government's power to protect those who wanted to work. The owners refused to talk with the union.

The governor sent in the National Guard to protect the mines. Roosevelt tried to get the union to end the strike. He promised to create a group to study the strike and find a solution. He said he would support this solution with all his power. But Mitchell refused, and the miners agreed with him.

The coal industry had a problem: most of the cost was miners' wages. If coal supply dropped, prices would go way up. In those days, there were no good substitutes for coal. Profits were low in 1902 because there was too much coal. So, the owners actually didn't mind a strike that lasted a while. They had huge piles of coal that became more valuable every day. It was against the law for owners to agree to stop production. But it was fine if miners went on strike. The owners welcomed the strike but strongly refused to recognize the union. They feared the union would control the coal industry by causing strikes.

Roosevelt kept trying to find a way to settle the strike. He even thought about having the government take over the mines. He considered putting the U.S. Army in charge to run the mines.

How Did J.P. Morgan Help End the Strike?

J.P. Morgan was a very powerful person in American finance. He had helped solve the 1900 strike. He was also deeply involved in this strike. His businesses included the Reading Railroad, which employed many miners. He had put George Baer in charge of the railroad. Baer spoke for the coal industry during the strike.

Morgan came up with another idea to solve the problem. He suggested that a group of people decide the outcome, which is called arbitration. But he also made sure the owners didn't have to officially talk with the union. Instead, each owner and their workers would talk directly with the special group. The owners agreed, but they wanted specific types of people on this group. They wanted a military engineer, a mining engineer, a judge, a coal expert, and an "eminent sociologist."

The owners were willing to accept a union leader as the "eminent sociologist." So, Roosevelt chose E. E. Clark, who led a railway union. Later, he added a Catholic bishop, John Lancaster Spalding, and Commissioner Wright. This made it a seven-member group.

What Was the Anthracite Coal Strike Commission?

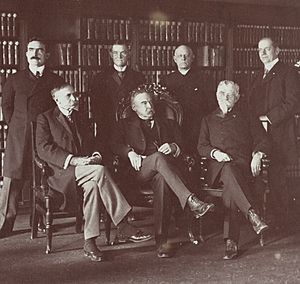

The anthracite strike finally ended on October 23, 1902, after 163 days. The special group, called the Anthracite Coal Strike Commission, started work the very next day. They spent a week visiting the coal mining areas. They also gathered information about the cost of living for miners.

The commission held hearings in Scranton for three months. They listened to 558 people who shared their stories. This included 240 people for the striking miners. There were also 153 for non-union miners and 154 for the coal owners. The commission itself called 11 witnesses. George Baer spoke for the coal owners. A famous lawyer named Clarence Darrow spoke for the workers.

The commission heard about some very tough conditions. But they decided that these were only a small number of cases. They generally found that living conditions in mining towns were good. They also thought that miners were only partly right about their wages not being enough.

Baer famously said that many miners didn't even speak English. Darrow, on the other hand, spoke powerfully about the struggles of the workers. He talked about working for democracy and a better future.

In the end, the commission tried to be fair to both sides. The miners had asked for a 20% wage increase. Most of them received a 10% increase. They had asked for an eight-hour day, but they were given a nine-hour day instead of the usual ten hours. The owners still didn't officially recognize the union. However, they had to agree to a six-person board to settle future problems. This board would have equal numbers of union and management representatives. Mitchell saw this as a win, even without official recognition.

What Happened After the Strike?

John Mitchell said that eight people died during the five-month strike. Some of them were strikers or their supporters. During the hearings, the company owners claimed that 21 men had been killed by strikers. Mitchell strongly disagreed. He even offered to quit if they could prove it.

The first death happened on July 1. A striker named Anthony Giuseppe was found shot near a coal mine. People thought the Coal and Iron Police guarding the area had shot through a fence. On July 30, there was fighting in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania. A large group of striking miners clashed with police. A merchant named Joseph Beddall was beaten to death. Reports from that time also describe other deaths and many injuries.

The way the Coal and Iron Police acted during the strike led to a big change. The Pennsylvania State Police was formed on May 2, 1905. The two police forces worked side-by-side for many years.

Workers and unions celebrated the strike's outcome as a big victory. Membership in other unions grew. People saw that unions could get real benefits for workers. Mitchell showed he was a great leader. He was able to unite miners from different backgrounds. This strike was a success because the federal government stepped in to help. President Roosevelt called his approach a "Square Deal" for everyone. This settlement was an important step in the Progressive era reforms that followed. There were no more major coal strikes until the 1920s.

Images for kids

More to Explore

- United States Anthracite Coal Strike Commission, Report to the President on the Anthracite Coal Strike of May–October, 1902 online edition

Music About the Strike

- Byrne, Jerry, and George Gershon Korson. On Johnny Mitchell's Train. Library of Congress, 1947. Audio. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200197134/.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |