Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery facts for kids

|

Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery

|

|

| Location | 1001 S. Washington Street, Alexandria, Virginia |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 12000516 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | August 15, 2012 |

The Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery is a special burial ground in Alexandria, Virginia. It was officially recognized as an important historical site on August 15, 2012. This cemetery was created in February 1864 during the American Civil War. It was a place to bury African Americans who had escaped slavery. These people were called "contrabands" or "freedmen."

The Union Army set up this cemetery. After the war, the Freedmen's Bureau helped manage it. The cemetery closed in late 1868. The last known burial happened in January 1869. For many years, the cemetery's history was forgotten. But in the late 1900s, people rediscovered it. Archeologists used special tools to find its boundaries and graves. The city of Alexandria bought the land. In 2014, the cemetery was reopened as a memorial park.

At first, African American soldiers from the United States Colored Troops were also buried here. But these soldiers wanted to be buried in the main Soldiers' Cemetery. This is now called Alexandria National Cemetery. So, in January 1865, the soldiers' remains were moved.

Why Was the Cemetery Needed?

Life for Escaped Slaves During the Civil War

During the American Civil War, the Union Army took control of Alexandria, Virginia. This created a huge chance for African Americans who had escaped slavery. Many people fled to areas controlled by the Union Army. Cities like Alexandria and Washington offered them safety. They were protected from their former enslavers. These cities also offered jobs for the refugees.

The Union Army turned Alexandria into a major supply center. It became a hub for transportation and hospitals. All these operations were under army control.

What Were "Contrabands"?

Before 1863, people who escaped slavery were still legally considered property. The Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, changed this. To avoid returning these people to their owners, the Union Army called them "contraband property." This term meant they would not have to send them back to slave owners. If they didn't use this term, Union soldiers would be breaking the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

New Opportunities for African Americans

African American men and women found many jobs with the U.S. Army. They worked as construction workers and nurses. They also worked as longshoremen, painters, and wood cutters. Other jobs included teamsters, laundresses, cooks, and gravediggers. Many became personal servants. Eventually, some joined the army as soldiers and sailors. They also worked as day laborers for other citizens.

Alexandria's population grew very fast. By the fall of 1863, it had 18,000 people. This was an increase of 10,000 people in just 16 months.

Challenges Faced by Freed People

Many people arrived in Alexandria in poor health. They were often malnourished after walking long distances. They lived in barracks or built their own shelters. These living areas were very crowded. Sanitation was poor. Because of this, diseases like smallpox and typhoid spread easily. Death was common, just like in most army camps. More than half of those buried in the cemetery were African American children under five years old.

Establishing the Cemetery

In February 1864, hundreds of people had died. The commander of the Alexandria military district, General John P. Slough, took some undeveloped land. It was at the corner of South Washington and Church streets. The land belonged to someone who supported the Confederacy. General Slough decided this land would be a cemetery. It was specifically for burying African Americans. Burials began in March of that year.

The cemetery was managed under General Slough's command. The Rev. Albert Gladwin, Alexandria's Superintendent of Contrabands, oversaw the burials. Each grave had a simple wooden marker, painted white.

In 1868, the federal government stopped managing the cemetery. This happened after Congress ended most of the Freedmen's Bureau's work. The land was returned to its original owners. Their descendants later sold the land to the Catholic Diocese of Richmond in 1917. An old newspaper article from 1892 said the wooden markers had decayed. It also said people had continued to use the site for burials unofficially. A "Book of Records" was kept, first by the Superintendent of Contrabands, then by the Freedmen's Bureau. It lists the names of 1,711 people buried there between 1864 and 1869.

Rediscovering the Cemetery

How the Cemetery Was Lost and Found

The cemetery disappeared from city maps after 1946. In 1955, a gas station was built on the site. Later, an office building was constructed there. People started paying more attention to the cemetery's history in 1987. This is when its story was rediscovered.

When the Woodrow Wilson Bridge was being built, archeological surveys were done. They used ground penetrating radar (GPR) to find out if graves were still there. Some digging also took place to locate any remaining burials.

Creating a Memorial Park

In 1997, a group called "Friends of Freedmen Cemetery" was formed. Their goal was to make people aware of the cemetery. They also wanted to save it. The City of Alexandria began to buy the land. Their plan was to create a memorial park.

In 2008, a design competition was held for the memorial. People from 20 countries sent in ideas. A design by C.J. Howard from Alexandria was chosen. The cemetery memorial opened in September 2014. It features a sculpture called The Path of Thorns and Roses by Mario Chiodo. This sculpture is in the center of the park. The names of the people buried at the site are etched into bronze plaques. These names came from the old "Book of Records."

The Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in August 2012. In 2015, it became part of the National Park Service's National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. This network includes sites important to the history of enslaved people escaping to freedom.

Historical Markers

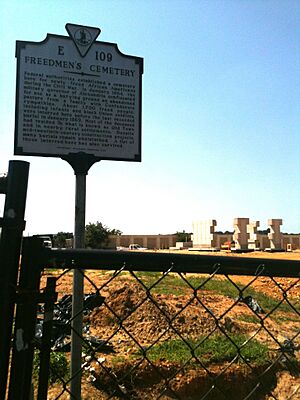

A historical marker was put up in 2000 by the Virginia Department of Historic Resources. It tells the story of the cemetery:

Freedmen's Cemetery Federal authorities established a cemetery here for newly freed African Americans during the Civil War. In January 1864, the military governor of Alexandria confiscated for use as a burying ground an abandoned pasture from a family with Confederate sympathies. About 1,700 people, including infants and black Union soldiers, were interred here before the last recorded burial in January 1869. Most of the deceased had resided in what is known as Old Town and in nearby rural settlements. Despite mid-twentieth-century construction projects, many burials remain undisturbed. A list of those interred here has also survived.

A list of those interred is displayed at the Memorial. It also includes this historical note:

Besides the school in the barracks there are others in the city, which are self sustaining, containing one hundred and fifty pupils. It is an astonishing fact, which ought to be placed upon record ... [ellipsis in the original] that out of the two thousand people collected at Alexandria, there are four hundred children sent daily to school. The first demand of these fugitives when they come into the place is, that their children may go to school.