Coultershaw Wharf and Beam Pump facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Coultershaw Beam Pump |

|

|---|---|

The Coultershaw Beam Pump fountain pump output on a working day

|

|

| Location | Petworth, West Sussex, England |

| OS grid reference | SU9720819409 |

| Elevation | 9 metres (30 ft) |

| Built | 1782 |

| Built for | 3rd Earl of Egremont |

| Restored | 1980 |

| Restored by | Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society |

| Owner | The Coultershaw Trust |

| Official name: Coultershaw Beam Pump | |

| Reference no. | 1005817 |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

Coultershaw Bridge is a small place located about 1.5 miles south of Petworth in West Sussex, England. It's where the A285 road crosses the River Rother.

For many years, a water mill stood here. In 1782, the 3rd Earl of Egremont installed a special machine called a beam pump. This pump used water power to send water from the river all the way to Petworth and his home, Petworth House.

The old mill was taken down in the 1970s. However, the Coultershaw Beam Pump was saved and fixed up. It is now a scheduled monument, which means it's an important historical site. You can visit it on summer weekends to see how it works!

Contents

What's in a Name?

Long ago, in Saxon times, this area was called "Cuóheres Hóh." This name meant "Couhere's spur of land." Over hundreds of years, the name changed many times. By 1800, it finally became known as "Coultershaw."

Coultershaw Mill: A Look Back

A mill has likely been at Coultershaw for a very long time. The Domesday Book from 1086, which was a big survey of England, probably mentioned this mill.

Over the centuries, the mill changed owners many times. It was once owned by the Percy family. Later, it became part of the Petworth estate, which was owned by the Earls of Egremont.

In 1910, the mill was updated. The old water wheel was replaced with a water turbine. This made the milling process more modern. Sadly, a fire destroyed the mill in 1923. A new, less attractive building was put up in its place.

The Gwillim family ran the mill from the early 1900s until 1972. After John Gwillim passed away in 1972, the mill stopped working. The building was taken down the next year. Luckily, the important beam pump and water wheel were saved.

Petworth's Water Story

Before pipes, people in Petworth got water from springs. One famous spring was called the Virgin Mary Spring.

In the early 1500s, the first piped water system was built. A lead pipe brought water from springs to Petworth House and public fountains. Over time, these pipes wore out. The town and the Earls worked together to keep the water flowing.

By the late 1700s, the old system wasn't enough. So, in 1782, the 3rd Earl of Egremont installed the beam pump at Coultershaw Mill. This pump pushed water up to reservoirs in Petworth. This river water was not for drinking. It was used for other things, like in breweries.

In 1874, a doctor found a problem. The town's sewage was flowing into the River Rother, upstream from the pump. This meant the water pumped to the town was polluted. People were getting sick because they used this river water for drinking.

New ideas for clean water were suggested. In 1882, a new pumping station was built. It brought clean spring water to Petworth. The old river water system was then used only for the reservoir in Petworth Park.

Coultershaw Wharf: A Busy Port

From 1791 to 1794, the Third Earl of Egremont helped make the River Rother easier for boats to use. This was called the Rother Navigation. It allowed boats to travel between the River Arun and Midhurst.

Coultershaw became a very busy place for boats. It was the closest port to Petworth. Goods like fertilizer, coal, and building materials came in. Farm products and timber were sent out. Coultershaw Wharf handled more than half of all the traffic on the navigation.

In 1800, a new bridge was built at Coultershaw. This bridge helped reroute the main road to Petworth. The old bridge was taken down, and its stones were used for the new one.

The navigation was busiest between 1823 and 1863. But then, railways started to become popular. In 1859, a railway line opened to Petworth. This greatly reduced the amount of traffic on the canal. By 1888, commercial boats stopped using the navigation.

Today, two bridges remain at Coultershaw Wharf. One carries the busy A285 road. The other is over the old navigation channel.

The Amazing Beam Pump

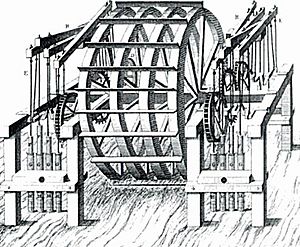

The beam pump was installed in 1782. It was designed to pump water from the River Rother to Petworth House. Petworth House is 1.5 miles north of the mill and much higher up. The pump's design is similar to older pumps used under London Bridge.

This type of pump is very rare now. The Coultershaw pump is the only one of its kind still working.

The pump works using a large water wheel. This wheel turns a special rod called a crankshaft. The crankshaft moves three long wooden beams up and down. These beams then push water through pipes. The pump could move a lot of water, about 20,000 gallons per day!

The original water wheel was made of wood. It was replaced in the mid-1800s with an iron wheel. The pump survived the fire that destroyed the mill in 1923. It kept working until about 1960. Because it's so unique, the restored Coultershaw pump was made an Ancient Monument in 1980.

Bringing it Back to Life

Even though the mill was torn down in 1973, the beam pump and water wheel were saved. In 1976, the Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society got permission to fix the pump. Volunteers from the society worked hard to restore it. They wanted to open it to the public.

They even found an old barn from the nearby Goodwood estate. They moved it and rebuilt it over the pump. This barn now protects the pump and serves as a visitor center.

By early 1980, the restoration was almost done. The water wheel started running again in March 1980. Two months later, the pump and a fountain outside were working together. On July 4, 1980, the Beam Pump was officially started. Two days later, it opened to the public for the first time.

Today, the pump still works. It supplies water to a fountain outside the visitor center.

Visiting Coultershaw

The museum is open to the public on the first and third Sundays. It's also open on all bank holiday Mondays from April to September.

Besides the beam pump, you can see other types of water pumps. You can also explore the mill pond and the old navigation channel. The River Rother here is popular for fishing, with lots of chub and barbel.

New Green Energy

In July 2012, something new and exciting happened at Coultershaw. An Archimedes' screw water turbine was installed. This turbine generates "green" electricity from the river's flow. It's one of the first of its kind in southeast England.

The large, six-ton screw can produce a lot of electricity. This power is sent to the National Grid, which supplies electricity to homes and businesses.

The Coultershaw Trust has continued to improve the site. In July 2013, a new boardwalk and footbridge were added. This allows visitors to explore more of the area. The old lock has also been made into a footpath. Visitors can now walk through it and see its historic walls.

Points of interest

| Point | Coordinates (Links to map resources) |

OS Grid Ref | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coultershaw | 50°57′57″N 0°37′02″W / 50.965972°N 0.617222°W | SU97211941 | |

| Shulbrede Priory | 51°03′42″N 0°45′04″W / 51.061716°N 0.750973°W | SU87622989 | |

| Virgin Mary Spring | 50°58′54″N 0°35′58″W / 50.981671°N 0.599408°W | SU98412118 | |

| Boxgrove Paddock | 50°59′17″N 0°37′27″W / 50.987992°N 0.624294°W | SU96652185 | |

| Conduit Field | 50°59′04″N 0°37′23″W / 50.984336°N 0.623048°W | SU96702140 | |

| Lawn Hill (reservoir) | 50°59′24″N 0°36′47″W / 50.990017°N 0.612978°W | SU97442209 | |

| Percy Row (reservoir) | 50°59′05″N 0°36′26″W / 50.984822°N 0.607149°W | SU97862152 | |

| Haslingbourne (pumping station) | 50°58′26″N 0°36′09″W / 50.973885°N 0.602491°W | SU98212031 | |

| Cottage Hospital (reservoir) | 50°59′07″N 0°35′24″W / 50.985246°N 0.590039°W | SU99062159 | |

| Rotherbridge | 50°58′23″N 0°37′29″W / 50.973000°N 0.624800°W | SU96652019 | |

| Uppark water pump | 50°57′58″N 0°53′06″W / 50.966000°N 0.884914°W | SU78401910 | Location of pump |

| Bignor Park | 50°55′43″N 0°35′18″W / 50.928616°N 0.588408°W | SU99301530 | Location of pump |

| Woolbeding House | 50°59′49″N 0°45′21″W / 50.997067°N 0.755915°W | SU87402270 | Location of pump |

| Cocking Foundry | 50°57′35″N 0°44′36″W / 50.959610°N 0.743390°W | SU88241861 |

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |