Cucuteni–Trypillia culture facts for kids

The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture was an ancient group of people who lived in Southeast Europe a very long time ago, from about 5500 to 2750 BC. This was during the New Stone Age and Copper Age. Their land stretched from the Carpathian Mountains to the Dniester and Dnieper rivers. Today, this area covers much of Moldova, western Ukraine, and northeastern Romania. It was a huge area, about 350,000 square kilometers (135,000 sq mi)!

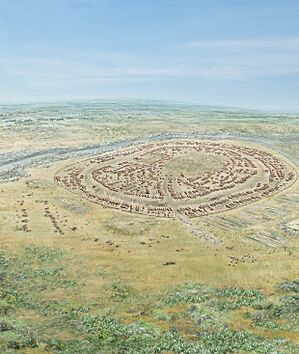

Most Cucuteni–Trypillia villages were small, but they were built close together. During their middle period (around 4000 to 3500 BC), these people built some of the largest settlements in ancient Europe. Some of these "mega-sites" had thousands of buildings and might have been home to 20,000 to 46,000 people. These were the biggest settlements in Eurasia and possibly the whole world at that time, even larger and older than some famous cities in Mesopotamia.

The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture was quite advanced. They had special public bathing areas. They also used a potter's wheel around 4500 BC, which is the oldest one ever found. This was hundreds of years before wheels were used in Mesopotamia! They might have even invented early forms of civilization.

One interesting thing about this culture is that they regularly burned down their own villages. Each village lasted about 60 to 80 years before it was burned. Why they did this is still a mystery to experts. Sometimes, they rebuilt new villages right on top of the old burned ones. One place in Romania, called Poduri, has thirteen layers of old villages built one on top of another!

Contents

How the Culture Got Its Name

This ancient culture got its name from two places where its remains were first found.

In Romania, it was named after a village called Cucuteni. In 1884, a person named Teodor T. Burada found pieces of pottery and clay figures there. He and other experts started digging in Cucuteni in 1885. They shared their exciting discoveries in Paris in 1889.

Around the same time, similar findings were made in Ukraine. A Czech-Ukrainian expert named Vincenc Chvojka found artifacts near Kiev. Then, in 1897, more similar items were found in a village called Trypillia. Because of this, the culture became known as the 'Trypillia culture' in Ukraine and later in Russia.

Today, experts know that the finds from Romania, Ukraine, and Moldova all belong to the same culture. In Romania, it's usually called the Cucuteni culture. In Ukraine, it's called the Trypillia culture. In English, people often use "Cucuteni–Trypillia culture" to talk about the whole group.

Where They Lived

The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture thrived in the areas that are now Moldova, eastern and northeastern Romania, and parts of western, central, and Southern Ukraine.

Their territory stretched from the Danube River to the Black Sea and the Dnieper River. It included the central Carpathian Mountains and the flatlands around them. The main part of their land was around the middle and upper Dniester River. During the time they lived, Europe was warmer and wetter than it had been in a long time. This was great for farming.

By 2003, about 3,000 sites belonging to this culture had been found. These sites ranged from small villages to huge settlements with hundreds of homes. Some were even surrounded by multiple ditches for protection.

How Their Time Was Divided

Experts divide the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture into three main periods: Early, Middle, and Late. Each period saw changes in how they lived and the things they made.

- Early Period: 5800 to 5000 BC

- Middle Period: 5000 to 3500 BC

- Late Period: 3500 to 3000 BC

Early Period (5800–5000 BC)

The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture started from older cultures in the region. Over time, it grew and spread from the Prut–Siret river area into Ukraine. Most early villages were built near rivers.

At first, many homes were pit-houses, which were partly dug into the ground. But more and more, they built houses above ground using clay. The floors and fireplaces were made of clay, and the walls were made of wood or reeds covered with clay. Roofs were likely made of straw or reeds.

These people were farmers and herders. They also fished and gathered wild foods. They grew wheat, rye, and peas. They used tools made of antler, stone, and bone for farming. Women were likely in charge of making pottery, textiles, and clothes. Men hunted, took care of animals, and made tools from flint, bone, and stone. Cattle were their most important animals, along with pigs, sheep, and goats. It's not clear if they had domesticated horses yet.

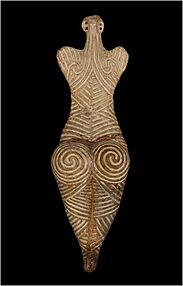

They made clay statues of women and small charms. Sometimes, they found copper items like bracelets and rings. Some experts think this shows that some people were richer than others, but this is still debated.

Early pottery was often smoky grey with raised designs. Later, they started painting their pottery before firing it. This change to painted pottery marks the start of the main Cucuteni–Trypillia culture.

Middle Period (5000–3500 BC)

During this time, the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture spread widely, from eastern Transylvania to the Dnieper River in Ukraine. Many people moved and settled along the Dnieper River. The population grew a lot, and new villages were built on high ground near rivers and springs.

Their homes were built with wooden poles in circles or ovals. They had log floors covered in clay, and walls made of woven branches covered in clay (called wattle-and-daub). A clay oven was usually in the center of the home. As more people lived there, they farmed more land. Hunting still helped provide food, but raising animals became more important.

They continued to use tools made of flint, rock, clay, wood, and bone. Copper tools like axes were rare, but they have been found. Pottery making became very skilled, though they still shaped pots by hand. Their pottery often had black spiral designs on yellow and red backgrounds. They also made large, pear-shaped pots for storing grain.

Many clay statues of female figures, animals, and house models have been found from this period. Some experts believe these female figures suggest that women played a very important role in their society.

Late Period (3500–3000 BC)

In the late period, the Cucuteni–Trypillia territory grew even more, reaching into northwest and northern Ukraine, and along the Dnieper River near Kiev. People living near the Black Sea met other cultures. Raising animals became even more important than hunting, and horses were used more.

Homes were built differently than before. Pottery designs changed from spirals to rope-like patterns. They also started burying their dead in the ground with special ceremonies. More and more items made of bronze, from other lands, were found as the culture came to an end.

Why the Culture Ended

Experts have different ideas about why the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture ended.

One idea is that they were taken over by another group of people called the Kurgan culture, who came from the steppes (flat grasslands) north of the Black Sea. Some experts, like Marija Gimbutas, believed the Kurgan people were more warlike and brought an end to the Cucuteni–Trypillia way of life. They think this happened between 3000–2800 BC.

Another idea is that climate change caused their decline. Around 3200 BC, the Earth's climate became colder and drier. This led to a severe drought in Europe. Since the Cucuteni–Trypillia people relied heavily on farming, their food supply would have suffered greatly. The Kurgan people, who were herders, might have been better able to survive these dry conditions. This theory suggests that the Cucuteni–Trypillia people didn't end violently, but slowly changed their way of life to become more like the herding cultures, eventually blending in with them.

Scientists have also studied ancient DNA from some Cucuteni–Trypillia people. This research shows that they had a mix of ancestry from early European farmers and some hunter-gatherer groups. Some later samples also show signs of ancestry from the steppe populations, which could support the idea of mixing with groups like the Kurgan people.

How They Lived and Traded

For most of its 2,750 years, the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture was quite stable. They shared many things with other Stone Age societies:

- Almost everyone was equal; there were no very rich or very poor people.

- There were no powerful leaders or kings.

- Their economy was simple, mostly for survival or sharing goods.

- They were farmers and raised animals.

In later times, like the Bronze Age, societies became more complex with different jobs and social classes. But the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture, even in its later years, was mostly an equal society.

There wasn't much need for trade because each family could mostly provide for itself. However, they did trade for certain materials like copper, which wasn't found everywhere. This simple trade network grew more complex over time, especially towards the end of their culture.

Towards the end of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture (around 3000 to 2750 BC), copper from other regions, especially the Balkans, started to appear more often. The Cucuteni–Trypillia people began to learn how to use copper to make tools and other items. This period is known as the Copper Age. Later, bronze items also started to show up. Their simple trade system was eventually replaced by the more complex trade networks of the groups who came after them.

What They Ate

The Cucuteni–Trypillia people were mostly farmers. Growing crops and raising animals was the main job for most people. Like other Stone Age cultures, most of their food came from grains. They grew wheat, oats, rye, millet, barley, and hemp. These grains were probably ground into flour and baked into flatbreads in clay ovens. They also grew peas and beans, apricots, and plums. There's also some evidence they might have kept bees for honey.

They raised animals like cattle, pigs, sheep, and goats. Cattle were the most important. There's also evidence that they used oxen to pull things.

They found remains and pictures of horses at their sites. It's not certain if these horses were wild or if they had started to tame them. Horses could have been used for meat or for work.

Hunting also added to their diet. They used traps, bows and arrows, spears, and clubs. They hunted animals like red deer, wild boar, and bears.

How They Got Salt

The oldest known salt works in the world is in Romania, near a village called Lunca. It was used by the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture. They got salt from salty spring water by boiling it in large pots. This created a thick salty liquid. Then, they heated this liquid in special ceramic pots until all the water was gone, leaving salt crystals stuck to the inside. They would then break the pot to get the salt out.

Getting enough salt was a big challenge for their largest villages. As they ate more grains and less salty meat and fish, they needed more salt in their diet. Their animals also needed extra salt. A large Cucuteni–Trypillia village might have needed tens of thousands of kilograms of salt each year! This salt wasn't found nearby, so it had to be brought from far away, probably by river, from places like the Black Sea coast or the Carpathian Mountains.

Amazing Technology and Art

The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture is famous for its unique villages, buildings, beautifully decorated pottery, and human-like and animal-like figures. At its peak, it was one of the most advanced societies of its time. They developed new ways to make pottery, build houses, farm, and weave textiles.

Their Villages

Some Cucuteni–Trypillia villages were enormous. For example, Talianki in Ukraine might have had 15,000 people and covered an area of 335 hectares. These Eastern European settlements were even older and larger than some of the famous city-states in Sumer.

Archaeologists have found many amazing objects from these ancient ruins. The biggest collections are in museums in Russia, Ukraine, and Romania.

As mentioned before, these villages were regularly burned down and then rebuilt every 60–80 years. Some experts think the people believed their houses were like living things, and that the whole village had a life cycle of death and rebirth.

Cucuteni–Trypillia homes were built in a few ways:

- Homes made of wattle-and-daub (woven branches covered in clay).

- Log homes.

- Homes partly dug into the ground.

Some homes were two stories tall. People sometimes decorated the outside of their homes with the same swirling red designs found on their pottery. Most houses had thatched roofs and wooden floors covered with clay.

Pottery Making

Most Cucuteni–Trypillia pottery was made by hand, using long coils of local clay. They would build up the shape coil by coil, then smooth the sides. This was a common way to make pottery in the Stone Age. However, there's also some evidence they used a simple, slow-turning potter's wheel, which was a very early invention.

Their pots were known for their beautiful swirling patterns and detailed designs. Sometimes, they carved designs into the clay before firing. In the early days, they used only rusty-red and white colors. Later, they added more colors and used more advanced techniques. The colors came from minerals like iron and manganese.

|

|

Towards the end of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture, they used special kilns (ovens) with controlled heat to make their pottery. These kilns could reach very high temperatures. As copper became more common, people focused more on working with metals, and pottery technology didn't advance as much.

Clay Figurines

Archaeologists have found many ceramic figures at Cucuteni–Trypillia sites. One famous example is the "Cucuteni Frumusica Dance," which shows four stylized female figures linked in a circle, possibly doing a ritual dance.

These figures are often thought to be religious objects. Many of them are female figures, which people sometimes call "goddesses." However, experts believe these figures might have been used for different purposes, like protection, and not all of them represent a goddess. There are so many of these figures that they are a key symbol of this ancient culture.

Textiles and Clothes

No actual pieces of Cucuteni–Trypillia fabric have survived because they are very old and the climate isn't right for preservation. But, impressions of woven fabrics have been found on pottery pieces. This shows that they commonly made woven cloth. They likely used warp-weighted looms, which are simple weaving machines. Some ceramic weights with holes suggest they were used with these looms, or perhaps to weigh down fishing nets.

Other pottery pieces suggest they also used a knitting-like technique called nalbinding.

Tools and Weapons

The Cucuteni–Trypillia people made tools from stone, bone, antler, and horn. Later, they also used copper. Flint was a common material for stone tools. These tools were probably attached to wooden handles, but the wood has not survived. Weapons are rare, which suggests that this culture was generally peaceful.

They used many types of tools, including:

- For woodworking: adzes, chisels, and scrapers made of stone, flint, or copper.

- For making stone tools: hammerstones and polishing tools.

- For textiles: knitting needles, shuttles, sewing needles made of bone or copper, and clay weights for looms.

- For farming: hoes and plows made of antler or horn, grinding stones for grain, and sickles with flint blades for harvesting.

- For fishing: harpoons and fish hooks made of bone or copper.

- Other tools: axes (including double-headed ones), clubs, knives, and daggers made of flint, bone, or copper.

Wheels

Some experts think the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture might have used wheels with wagons. However, only small models of animals and cups on four wheels have been found. These models date to the first half of the fourth millennium BC. They are often thought to be children's toys, but they do show that the idea of pulling objects on wheels existed. So far, there is no proof that they used wheels on real wagons.

Beliefs and Rituals

Some Cucuteni–Trypillia villages had special buildings in the center that archaeologists believe were sacred places or sanctuaries. Inside these buildings, they found objects that were clearly used for religious purposes. These finds give us clues about the beliefs and rituals of these people. Many homes also had religious objects.

Many of these objects are clay figures or statues. Archaeologists think these were like charms or totems, believed to have special powers to help and protect people. These Cucuteni–Trypillia figures are often called "goddesses." However, this term might not be completely accurate for all of them, as they might have been used for different purposes. Many museums in Eastern Europe have large collections of these figures, and they are a well-known symbol of the culture.

One mystery about the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture is that very few human remains or burial sites have been found. Even though archaeologists have explored very large villages, there is almost no evidence of how they buried their dead. This is a big question that experts are still trying to answer. The only place where human remains have been consistently found is Verteba Cave in Ukraine. It's still unclear why so few remains have been found elsewhere, or why male remains are particularly rare. It seems that in most cases, bodies were not formally buried within the village areas.

Images for kids

See also

- Barter tokens of the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture

- Chalcolithic Europe

- Copper Age

- Dnieper–Donets culture

- History of Ukraine

- Khvalynsk culture

- Linear Pottery culture

- Nebelivka (archaeological site)

- Neolithic Europe

- Old Europe

- Prehistoric Romania

- Prehistory of Southeastern Europe

- Proto-Indo-Europeans

- Samara culture

- Sredny Stog culture

- Varna culture

- Vinča culture

- Yamnaya culture