Diel vertical migration facts for kids

Diel vertical migration (DVM) is a fascinating daily movement pattern used by many ocean and lake creatures. The word "diel" means "over a 24-hour period." Imagine tiny animals like copepods, squid, and even some fish making a huge journey every single day!

These organisms travel up to the surface waters at night. They then return to the deeper, darker parts of the ocean or lakes during the day. This amazing migration is the largest synchronized movement of living things on Earth by total weight!

Why do they do it? Mostly to find food and to stay safe from predators. Changes in light, like sunrise and sunset, are the main triggers. But creatures also have internal "biological clocks" that help them know when to move. Sometimes, unusual events like a solar eclipse can even make them migrate at unexpected times!

The common swift bird also does something similar, flying up and down at dawn and dusk. It's like a bird version of this underwater journey!

How We Discovered This Amazing Journey

The idea of daily animal movements in water was first noticed by a French scientist named Georges Cuvier in 1817. He saw that tiny creatures called daphnia would appear and disappear in a regular daily pattern.

Later, during World War II, the U.S. Navy was using sonar to detect things underwater. They kept seeing a mysterious "false bottom" on their sonar screens. At first, they wondered if it was enemy submarines!

Scientists from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, led by Martin W. Johnson, helped solve the mystery. They figured out that this "deep scattering layer" was actually caused by huge groups of marine animals, like zooplankton, moving up and down. These groups were so dense they bounced back the sonar signals!

Since then, we've learned that many different types of plankton and other swimming animals (called nekton) perform some kind of vertical migration. These movements are very important for the ocean's food webs.

Different Ways Animals Migrate Vertically

Animals don't all migrate in the same way. There are a few main types of vertical migration.

Daily Diel Migration

This is the most common type, happening every 24 hours. Organisms move between the shallow surface waters and deeper zones.

Nighttime Migration

This is the most typical pattern. Animals swim up to the surface around sunset. They stay there all night to feed. Then, they swim back down to the deep waters around sunrise to hide.

Daytime Migration

Some creatures do the opposite! They come up to the surface at sunrise and stay there during the day. Then, they go back down when the sun sets. This is called reverse migration.

Twilight Migration

This pattern involves two trips up and two trips down in one day. Animals might come up at dusk, go down around midnight (the "midnight sink"), then come up again at sunrise before finally going back down for the day.

Seasonal Migration

Some animals change their depth depending on the time of year. For example, in the Arctic, during the "midnight sun" (when the sun never sets), some tiny organisms called foraminifera stay at the surface all the time. There's no darkness to tell them to go down!

Larger zooplankton, like some copepods, also show seasonal changes. They store up lots of fat (lipids) in the summer and fall. Then, they swim deep down to spend the winter, using their stored energy. This helps move carbon from the surface to the deep ocean.

Life Stage Migration

Sometimes, how an animal migrates depends on its age or life stage. Young animals might migrate differently than adults. For example, older, larger copepods often migrate deeper during the day than younger, smaller ones. This might be because bigger animals are easier for predators to spot.

What Makes Animals Migrate?

Many things can trigger vertical migration. Some triggers come from inside the animal (endogenous factors), and others come from the environment (exogenous factors).

Internal Triggers

Biological Clocks

Animals have internal "biological clocks" that act like a natural alarm system. These clocks help them know when to expect changes in their environment, like day and night. This allows them to prepare for their daily migration.

Scientists have seen that some copepods will continue their daily migration patterns in a lab, even when it's always dark. This shows their internal clock is at work!

Body Size

An animal's size can affect its migration. Smaller individuals of some fish, like bull trout, tend to stay deeper than larger ones. This is likely because smaller animals are more vulnerable to predators.

External Triggers

Light

Light is the most important signal for vertical migration. Animals react to changes in how bright the light is and even the color of the light.

Temperature

Animals might move to depths with temperatures that suit them best. Some fish, for instance, go to warmer surface waters at night to help them digest their food.

Salinity

Changes in the saltiness of the water can also make organisms move. If the water becomes too salty or not salty enough, they might seek out a more comfortable depth.

Pressure

Animals can sense changes in water pressure. When pressure increases (meaning they are going deeper), many tiny zooplankton will swim upwards. When pressure decreases, they might sink or swim downwards.

Predator Smells

Some predators release special chemicals, like a "smell," into the water. These chemicals can warn prey animals that a predator is nearby. This might cause the prey to swim deeper to avoid being eaten. For example, tiny Daphnia will stay in deeper waters if they sense a fish predator, even if the fish is too small to eat them!

Tidal Movements

In some areas, like estuaries (where rivers meet the sea), animals might move with the tides. They might swim higher in the water during incoming tides.

Why Do They Migrate?

Scientists have several ideas about why animals make these daily journeys.

Avoiding Predators

This is one of the biggest reasons. Many predators, like fish, use light to see their prey. By staying in deeper, darker waters during the day, smaller animals can hide. They come up to the surface at night when it's safer to feed.

Animals that migrate often stay in groups, which can offer protection. Smaller, harder-to-see animals might start their upward journey earlier than larger ones. This makes sense if they are trying to avoid being seen by hungry predators. Even squid will delay their migration if they sense dolphins nearby, as dolphins hunt using sound.

Saving Energy

Some animals might migrate to save energy. For example, male dogfish might "hunt warm and rest cool." They stay in warmer surface waters just long enough to eat. Then, they return to cooler, deeper waters where their bodies use less energy.

Also, some animals might feed in cold, deep water during the day. Then, they move to warmer surface waters at night to help them digest their meal faster.

Traveling and Spreading Out

Animals can use different ocean currents at various depths to find new food sources or to stay in a specific area.

Protection from UV Light

Sunlight can penetrate into the water. Too much ultraviolet (UV) light can harm small organisms, especially near the surface. Migrating deeper during the day helps them avoid this damage.

Water Clarity

The clarity of the water also plays a role. In cloudy waters, predators might be the main reason for migration. But in very clear waters, where UV light travels deeper, avoiding UV damage might be more important.

Surprising Migration Events

Sometimes, unusual events can change migration patterns.

For example, in the Arctic during the "midnight sun," the sun never sets for weeks. Without the usual light cues, some tiny organisms stop their daily migration. They stay at the surface to feed on abundant food or to help their internal algae photosynthesize.

A solar eclipse can also cause a sudden, temporary migration. When the sun is blocked during the day, the light intensity drops quickly. This sudden darkness can trick plankton into thinking it's nighttime, causing them to swim towards the surface!

Why This Journey Matters for the Ocean

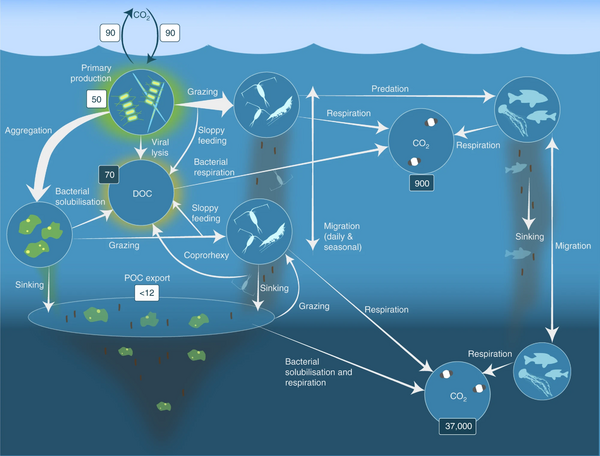

Diel vertical migration is super important for something called the biological pump. This "pump" is how the ocean moves carbon dioxide (CO2) and nutrients from the surface down to the deep sea. It's a huge process, and migration makes it much more efficient!

The deep ocean relies on nutrients falling down from above. This falling material is called "marine snow." It's made of dead animals, tiny microbes, fecal matter (poop!), and other bits.

When organisms like zooplankton migrate up to the surface at night, they eat. Then, when they swim back down to the deep during the day, they release their fecal pellets. These pellets sink much faster than if they were released at the surface. This "active transport" means nutrients reach the deep ocean much quicker. It's like a fast delivery service for the deep-sea ecosystem!

Large gelatinous animals called salps are especially good at this. They eat a lot at the surface and release very large fecal pellets deep down. These big pellets sink quickly, carrying even more small particles with them.

Also, the "lipid pump" (mentioned earlier with copepods storing fat) helps move carbon. When copepods store fat and go deep for winter, they are essentially taking carbon from the surface and moving it to the deep ocean. When they use this fat for energy, they release CO2 deep underwater, helping to store carbon away from the atmosphere.

So, while scientists are still learning all the reasons why animals migrate vertically, it's clear that these daily journeys are vital for the health and balance of our oceans.

See also

- Krill

- Phytoplankton

- Primary production

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |