Dyirbal language facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Dyirbal |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Northeast Queensland | |||

| Ethnicity | Dyirbal, Ngajanji, Mamu, Gulngai, Djiru, Girramay | |||

| Native speakers | 21 (2021 census) | |||

| Language family | ||||

| Dialects |

Jirrbal

Mamu

Djirru

Walmalbarra

|

|||

| AIATSIS | Y123 | |||

Area of historical use

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

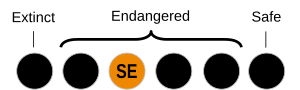

Dyirbal (pronounced JER-buhl) is an Aboriginal language from northeast Queensland, Australia. The Dyirbal people traditionally speak it. In 2021, only 21 people were reported to speak Dyirbal. It belongs to the small Dyirbalic group, which is part of the larger Pama–Nyungan family. Dyirbal is famous among language experts because it has many unique features.

Sadly, since a detailed book about Dyirbal grammar was published in 1972, fewer and fewer young people have learned the language. This means Dyirbal is slowly moving closer to disappearing.

Contents

What are the Dyirbal dialects?

The Dyirbal language has many different forms called dialects. A researcher named Robert Dixon believed there were once about 10 dialects of Dyirbal.

Some of these dialects include:

- Dyirbal (or Jirrbal), spoken by the Dyirbalŋan people.

- Mamu, spoken by groups like the Waɽibara and Mandubara.

- Giramay (or Girramay), spoken by the Giramaygan.

- Gulŋay (or Gulngay), spoken by the Malanbara.

- Dyiru (or Djirru), spoken by the Dyirubagala.

- Ngadyan (or Ngadjan), spoken by the Ngadyiandyi.

- Walmalbarra

People who spoke these dialects often thought they were speaking completely different languages. However, Robert Dixon grouped them as dialects because they were very similar. Some shared as much as 90% of their words! Since the speakers didn't have one name for the whole language, Dixon chose "Dyirbal." He picked this name because Jirrbal was the dialect with the most speakers when he studied it.

Which languages are Dyirbal's neighbors?

Many other Aboriginal languages were spoken near the different Dyirbal dialects. These included:

How does Dyirbal sound?

Dyirbal has fewer places where sounds are made in the mouth for its "stop" (like 'p', 't', 'k') and "nasal" (like 'm', 'n') sounds. Most other Aboriginal languages have more. This is because Dyirbal doesn't have the same differences between sounds made with the tongue at the teeth, the roof of the mouth, or curled back.

Like most Australian languages, Dyirbal doesn't really tell the difference between sounds like 'b', 'd', 'g' (voiced) and 'p', 't', 'k' (voiceless). When writing Dyirbal, people usually use 'b', 'd', 'g' because these sounds are closer to how English speakers say 'b', 'd', 'g'.

Dyirbal has three main vowel sounds: 'i' (like in sit), 'a' (like in father), and 'u' (like in put). Sometimes, the 'u' sound can sound like 'o', and 'a' can sound like 'e', depending on where they are in a word.

When you say a Dyirbal word, the first part (syllable) always gets the stress. Then, usually every other syllable after that gets stress, except for the very last one, which is never stressed. This means you won't hear two stressed syllables right next to each other.

What are Dyirbal's grammar rules?

Dyirbal is famous for its unique system of noun classes. It has four main groups for nouns, which are often divided by meaning:

- Group I: Most living things, especially men.

- Group II: Women, water, fire, violence, and some special animals.

- Group III: Edible fruit and vegetables.

- Group IV: Other things that don't fit into the first three groups.

The second group, which includes "women, fire, and dangerous things," even inspired the title of a famous book by George Lakoff!

Dyirbal's grammar also has a special way of marking who does what in a sentence. This is called a split-ergative system. It means that how words are changed (their "case") depends on who is speaking. If you use "I" or "you" (first or second person pronouns), the language acts more like English. But for other people or things, it uses a different system.

What was the Dyirbal taboo system?

In the past, Dyirbal culture had a very strict taboo system. This system meant that a person was not allowed to speak directly to certain relatives. These included their mother-in-law, child-in-law, and certain cousins. People also couldn't look directly at or get too close to these relatives.

When these taboo relatives were nearby, people had to use a special, more complex form of the language. This special language had the same sounds and grammar rules as the everyday language. However, almost all the words were different! Only four words, which referred to grandparents, were the same in both forms.

This taboo rule worked both ways. So, a person couldn't speak to their mother-in-law, and the mother-in-law also couldn't speak to her son-in-law. This rule was also in place, though less strictly, between people of the same gender. For example, a man should use the special respectful speech around his father-in-law.

The special language used in front of taboo relatives was called Dyalŋuy. The everyday language was called Guwal. Dyalŋuy had far fewer words than Guwal. This meant speakers had to be very clever with their words to get their message across. For example, in Dyalŋuy, there was only one word for "to ask." But in Guwal, there were four different words for "to ask," "to invite," or "to keep asking."

To get around this limited vocabulary, Dyirbal speakers used many clever language tricks. This has taught linguists a lot about how Dyirbal words get their meaning. For example, Guwal had separate words for "break" (when something breaks by itself) and "break" (when someone breaks something). But in Dyalŋuy, they would add a special ending to the word "break" to show if something broke by itself.

The words in Dyalŋuy came from a few places. Some were borrowed from the everyday language of nearby groups. Others were created by changing the sounds of words from their own everyday language. Some were even borrowed from the Dyalŋuy style of a neighboring language.

It's thought that Dyirbal children learned the Dyalŋuy speech style a few years after learning their everyday language. They would learn it from their cousins, who would use Dyalŋuy around them. By the time they reached puberty, children were probably fluent in Dyalŋuy and knew when to use it. This kind of "mother-in-law language" was common in many Aboriginal Australian languages. However, the Dyirbal taboo system stopped being used around 1930.

What is Young Dyirbal?

In the 1970s, some Dyirbal and Giramay speakers bought land and formed a community. In this community, the language started to change. A new form of Dyirbal appeared, which researcher Annette Schmidt called "Young Dyirbal" (YD). This new form is different from "Traditional Dyirbal" (TD).

Young Dyirbal's grammar is different from Traditional Dyirbal. In some ways, it has become more like English. For example, the special way of marking who does what in a sentence (the ergative system) is slowly disappearing in Young Dyirbal. Instead, it uses a style more similar to English.

See also

In Spanish: Idioma dyirbal para niños

In Spanish: Idioma dyirbal para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |