Early Middle Japanese facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Early Middle Japanese |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 中古日本語 | ||||

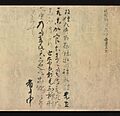

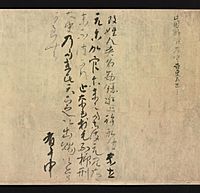

The oldest cursive kana written in early Heian period, indicating the birth of hiragana from Man'yōgana.

|

||||

| Region | Japan | |||

| Era | Evolved into Late Middle Japanese at the end of the 12th century | |||

| Language family | ||||

| Early forms: |

Old Japanese

|

|||

| Writing system | Hiragana, Katakana, and Han | |||

| Linguist List | ojp Described as "The ancestor of modern Japanese. 7th–10th centuries AD." The more usual date for the change from Old Japanese to Middle Japanese is ca. 800 (end of the Nara era). | |||

|

||||

Early Middle Japanese (中古日本語, Chūko-Nihongo) was a form of the Japanese language spoken between the years 794 and 1185. This time is known as the Heian period (平安時代) in Japan. It came after Old Japanese (上代日本語). Some people call it "Late Old Japanese," but "Early Middle Japanese" is a better name. This is because it was more like Late Middle Japanese (中世日本語, after 1185) than Old Japanese (before 794).

Contents

How Did Early Middle Japanese Begin?

Before Early Middle Japanese, people in Japan used Chinese writing to write Japanese. This was a bit tricky. During the Early Middle Japanese period, two new writing systems were created. These were the hiragana and katakana scripts.

These new scripts made writing much easier. This led to a golden age for Japanese literature. Many famous books were written during this time. Examples include The Tale of Genji, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, and The Tales of Ise.

How Was Early Middle Japanese Written?

Early Middle Japanese used three main ways of writing.

Man'yōgana: Borrowed Sounds

At first, Japanese was written using something called Man'yōgana (万葉仮名). This name means "ten thousand leaves borrowed labels." It refers to the Man'yōshū poetry book. In Man'yōgana, Chinese characters were "borrowed" to represent Japanese sounds. It was like using a Chinese character that sounded like a Japanese syllable.

Hiragana: Simple and Flowing

Over time, people started writing Man'yōgana in a more flowing, cursive way. This led to the creation of hiragana (平仮名). Hiragana means "flat" or "simple borrowed labels." It became a very popular way to write.

Katakana: Partial Characters

At the same time, Buddhist monks developed a simpler way to write. They took small parts of Chinese characters to represent sounds. This led to katakana (片仮名). Katakana means "partial" or "piece borrowed labels." It was often used for notes and shorthand.

Old vs. New Characters

Japan officially changed some Chinese characters in 1946. These new forms are called shinjitai (新字体). The older forms are called kyūjitai (旧字体). When you read old Japanese texts today, they are usually written with the newer shinjitai. However, if you see a direct quote from an old text, it might use the kyūjitai.

There are also differences in how words were spelled. For example, the Man'yōshū is spelled まんようしゅう in modern Japanese. But in Early Middle Japanese, it would have been まんえふしふ. These old spelling rules help us understand historical kana usage.

How Did Early Middle Japanese Sound?

The way Early Middle Japanese was spoken changed a lot over time.

Sound Changes

One big change was the loss of some special sound differences. In Old Japanese, there were two types of i, e, and o sounds. These differences slowly disappeared in Early Middle Japanese. For example, around the year 800, the two ko sounds were still written differently. But later, this difference was lost.

By the 10th century, the e and je sounds merged into je. By the 11th century, the o and wo sounds merged into wo.

Chinese Influence on Sounds

More and more words from the Chinese language were borrowed into Japanese. This changed how Japanese sounds were made.

- New sounds like kw and kj were added.

- A new nasal sound, like the "ng" in "sing," was introduced.

- The length of vowels and consonants became important. This means that saying a sound for a longer time could change a word's meaning.

These changes also led to new types of syllables.

Grammar of Early Middle Japanese

Early Middle Japanese sentences usually followed a "subject-object-verb" order. This means the person or thing doing the action came first. Then came the thing the action was done to. Finally, the action itself (the verb) came last. It was also an agglutinative language. This means words were built by adding small parts (suffixes) to a base word.

Understanding Sentences

Let's look at a famous line from The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter:

Romanization: ima wa mukasi, taketori no okina to ifu mono arikeri. Modern Japanese translation: 今からみるともう昔のことだが、竹取の翁という者がいた。 English translation: Long before the present, it is said that there was someone called Old Man Bamboo Cutter.

In Early Middle Japanese, a sentence could be broken down into smaller parts:

- Sentence (

文 ): A complete thought ending with a period (「。」). - Phrase (

文 節 ): A group of words that naturally go together by meaning. For example, 「今は」 (now) and 「昔」 (long ago) are phrases. - Word (

単 語 ): The smallest unit of meaning. For example, 「今」 (now) is a word.

Types of Words

Words in Early Middle Japanese were put into different groups:

- Words that cannot stand alone:

* Auxiliary particles (

- Words that can stand alone:

* Words without changing form: * Adverbs (

Auxiliary Particles

Auxiliary particles had many jobs. Here are some examples:

- Case particles (

格 助 詞 ): These show how a phrase relates to the next part of the sentence. For example, 「へ」 (he) means "to" or "towards." - Conjunctive particles (

接 続 助 詞 ): These connect different parts of a sentence. For example, 「ども」 (domo) means "even though." - Binding particles (

係 助 詞 ): These particles add emphasis or ask a question. They also change the form of the verb at the end of the sentence. This is called the "binding rule." For example, 「ぞ」 (zo) and 「なむ」 (namu) add emphasis. 「や」 (ya) and 「か」 (ka) ask questions. - Final particles (

終 助 詞 ): These usually come at the end of a sentence. They show different moods, like asking a question or making a strong statement. - Interjectory particles (

間 投 助 詞 ): These are similar to final particles but can appear more freely. They are often used as short pauses.

Verbs in Early Middle Japanese

Early Middle Japanese verbs changed their endings to show different meanings. This is called "conjugation." Most verbs had six forms. These forms could combine with helper verbs (auxiliary verbs) to show things like past tense, future tense, or if something was a question.

There were many verbs that sounded the same but had different meanings. For example, 「

Verb Forms

Early Middle Japanese verbs had nine different ways they could change their endings. These were grouped into "regular" and "irregular" conjugations.

There were 6 main forms for verbs:

- Irrealis (未然形): This form is used for things that haven't happened yet, or for possibilities.

- Infinitive (連用形): This form links to other verbs or auxiliary verbs. It can also act like a noun.

- Conclusive (終止形): This form ends a sentence.

- Attributive (連体形): This form describes a noun.

- Realis (已然形): This form is used for things that have already happened or are certain.

- Imperative (命令形): This form gives a command or order.

Auxiliary Verbs

Auxiliary verbs are like helper verbs. They attach to the main verb to add more meaning. They also change their own forms. To use an auxiliary verb, you need to know: 1. How it changes its form. 2. Which form of the main verb it needs to attach to. 3. What different meanings it can add.

For example, the auxiliary verbs 「る」 (ru) and 「らる」 (raru) had four main functions: 1. Passive mood: Showing that something is being done to the subject. Example: "is despised by people." 2. Slight respect: Showing politeness to someone. 3. Possibility: Showing that something can or might happen. Example: "It doesn't seem bow and arrow can shoot it down." 4. Spontaneous voice: Showing that something happens without someone's control. Example: "the sound of wind has made me startled."

Other auxiliary verbs could show:

- Voice: Like passive (something is done to the subject) or causative (someone makes something happen).

- Tense/Aspect: When something happened (past, present) or if it's ongoing or completed.

- Mood: The speaker's attitude, like if something is uncertain ("maybe"), an intention ("I shall"), or a suggestion ("let's").

- Polarity: If something is negative ("not").

Adjectives in Early Middle Japanese

There were two main types of adjectives: regular adjectives and adjectival nouns.

Regular Adjectives

Regular adjectives described nouns. They also changed their endings. There were two groups based on how their adverbial form ended:

- Those ending in 「-く」 (-ku).

- Those ending in 「-しく」 (-siku).

These adjectives also had special forms that combined with the verb 「

Adjectival Nouns

Adjectival nouns were a different kind of adjective. They came from nouns. They had two main types of endings:

- Nari (ナリ活用): These were contractions of the particle 「に」 (ni) and the verb 「あり」 (ari). For example, 「しづかなり」 (shizuka nari) meant "to be static" or "quiet."

- Tari (タリ活用): These were contractions of the particle 「と」 (to) and the verb 「あり」 (ari). Many tari adjectives came from Chinese words. For example, 「悄然たり」 (shōzen tari) meant "to be quiet" or "soft."

Images for kids

-

The oldest cursive kana written in early Heian period, showing how hiragana started from Man'yōgana.

See also

In Spanish: Japonés medio temprano para niños

In Spanish: Japonés medio temprano para niños

- Bungo

Sources

- Frellesvig, Bjarke (2010). A history of the Japanese language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN: 978-0-521-65320-6.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |