Edwin Howard Armstrong facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edwin H. Armstrong

|

|

|---|---|

Sketch of Armstrong, c. 1954

|

|

| Born | December 18, 1890 New York City, US

|

| Died | February 1, 1954 (aged 63) New York City, US

|

| Education | Columbia University |

| Occupation | Electrical engineer, inventor |

| Known for | Armstrong oscillator Armstrong Tower Armstrong phase modulator Autodyne FM broadcasting FM radio Frequency modulation Regenerative circuit Superheterodyne receiver KE2XCC W2XMN |

| Spouse(s) |

Marion MacInnis

(m. 1922) |

| Awards | IEEE Medal of Honor (1917) Holley Medal (1940) Franklin Medal (1941) IEEE Edison Medal (1942) Washington Award (1951) Wireless Hall of Fame (2001) |

Edwin Howard Armstrong (born December 18, 1890 – died February 1, 1954) was an American electrical engineer and inventor. He is famous for developing FM (frequency modulation) radio and the superheterodyne receiver system.

He held 42 patents for his inventions. He also received many awards, including the first Medal of Honor from the Institute of Radio Engineers (now IEEE). He was also given the French Legion of Honor. During World War I, he served in the U.S. Army Signal Corps and became a major. People often called him "Major Armstrong." He was recognized in the National Inventors Hall of Fame. He was also listed by the International Telecommunication Union as a great inventor. After his death, he was added to the Wireless Hall of Fame in 2001. Armstrong studied at Columbia University and later became a professor there.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Edwin Armstrong was born in the Chelsea area of New York City. He was the oldest of three children. His father worked for Oxford University Press, a company that published books. His family was comfortably middle class.

When he was eight, Armstrong got sick with a condition called Sydenham's chorea. This illness made him twitch, especially when he was excited or stressed. Because of this, he left public school and was taught at home for two years. To help his health, his family moved to a house in Yonkers. This house overlooked the Hudson River. His illness and time away from school made him a bit shy.

From a young age, Armstrong loved electrical and mechanical things. He was very interested in trains. He also liked heights. He built a tall antenna tower in his backyard. He even had a special chair to pull himself up and down the tower. This worried his neighbors! He did much of his early research in his parents' attic.

In 1909, Armstrong started studying at Columbia University in New York City. He studied electrical engineering. He was a very focused student. He liked to challenge old ideas. He believed that experimenting was more important than just using math formulas. He graduated from Columbia in 1913 with an electrical engineering degree.

After college, he worked as a laboratory assistant at Columbia. He never worked for a big company. Instead, he set up his own research lab at Columbia. He paid for his own projects and owned all his inventions. In 1934, he became a professor of Electrical Engineering at Columbia. He held this job for the rest of his life.

Armstrong's Key Inventions

The Regenerative Circuit

Armstrong started working on his first big invention while still in college. In 1906, Lee de Forest invented a vacuum tube called the "Audion." At first, people didn't fully understand how these tubes worked. Armstrong wanted to learn more. He used a special tool called an oscillograph to study them closely.

His big discovery was finding out that using "regeneration" (also called positive feedback) could make radio signals much stronger. This meant that radios could use loudspeakers instead of just headphones. He also found that if you increased the feedback enough, the vacuum tube could create its own radio waves. This meant it could be used as a radio transmitter.

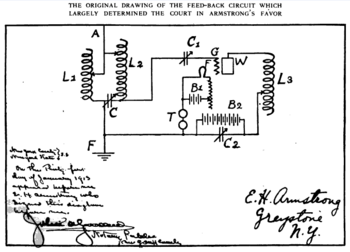

Armstrong applied for a patent for his regenerative circuit in 1913. He got the patent in 1914. However, Lee de Forest later claimed he had invented it first. This led to a long legal battle. Many other inventors also claimed to have invented similar ideas.

To pay for his legal costs, Armstrong allowed small radio companies to use his invention. In 1920, the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company bought the commercial rights to his regenerative and superheterodyne patents.

The legal fight over the regeneration patent went on for many years. It even went to the US Supreme Court twice. In the end, the court decided that Lee de Forest was the inventor. This decision surprised many engineers. Armstrong even tried to return his 1917 Medal of Honor, but the organization refused.

The Superheterodyne Circuit

During World War I, Armstrong joined the U.S. Army Signal Corps. He worked in Paris, France, to help improve radio communication for the Allies. He was promoted to Major. During both World Wars, Armstrong let the US military use his inventions for free.

During this time, Armstrong created the "superheterodyne" radio receiver. This invention made radio receivers much better at picking up signals. It also made them more selective, meaning they could tune into one station more clearly. This system is still used widely today.

The superheterodyne system works by mixing the incoming radio signal with another signal created inside the radio. This creates a new, fixed "intermediate frequency" signal. This new signal is easier to amplify and detect. Armstrong got a patent for this in 1919.

This patent was also challenged in court. A French inventor named Lucien Lévy had similar ideas. After more legal battles, the court decided that Lévy had invented some parts of the superheterodyne circuit first.

Even with the patent disputes, Armstrong worked with David Sarnoff of RCA. RCA started selling superheterodyne radios in 1924. They were a huge success and made a lot of money for RCA. These radios were so popular that RCA did not let other US companies use the technology until 1930.

The Super-Regeneration Circuit

During his legal battles, Armstrong made another accidental discovery. He found that by quickly "quenching" (stopping and restarting) the vacuum tube oscillations, he could get even more amplification. He called this "super-regeneration."

In 1922, Armstrong sold his super-regeneration patent to RCA. He received $200,000 and 80,000 shares of RCA stock. This made him RCA's largest shareholder. He said this invention earned him more money than his other two combined. RCA hoped to sell super-regenerative radios. However, the circuit was not selective enough for regular broadcast radios.

The Invention of FM Radio

Early radio communication used amplitude modulation (AM). It had a big problem: "static" interference. This was noise from thunderstorms and electrical equipment. Many inventors tried to get rid of static, but with little success. In the mid-1920s, Armstrong started looking for a solution.

Some people had tried using frequency modulation (FM) transmissions. Instead of changing the strength of the radio wave (like AM), FM changes the frequency of the wave. An earlier study by John Renshaw Carson suggested that FM wouldn't be better than AM. However, Carson's study only looked at "narrow-band" FM.

Armstrong began his own research into FM in 1928. He worked secretly in a lab at Columbia University. He developed "wide-band" FM. He discovered that this type of FM had huge advantages over narrow-band FM. In a wide-band FM system, the changes in the radio wave's frequency are much larger than the sound signal. This helps to block out noise much better.

He received five US patents for his new FM system in 1933. He showed his new system to David Sarnoff, the president of RCA, in 1934. RCA was more interested in developing TV broadcasting at the time. They told Armstrong to remove his equipment from the Empire State Building where he was testing it.

Since RCA wasn't interested, Armstrong decided to fund his own development. He worked with smaller radio companies like Zenith and General Electric. He believed that FM could replace AM radio within five years. This would also help the radio manufacturing industry, which was struggling during the Great Depression.

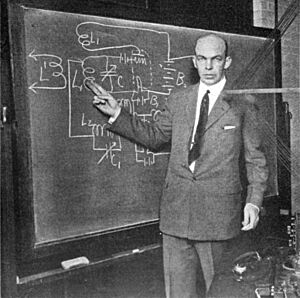

In 1936, Armstrong gave a presentation of his new system to the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC). He played a jazz record using AM radio, then switched to FM. Everyone was amazed by the clear sound. A reporter wrote that it sounded like the jazz band was in the same room. Many engineers called it one of the most important radio developments ever.

In the late 1930s, the FCC looked for ways to add more radio stations and improve sound quality. Armstrong worked to convince the FCC that FM was the best way. In 1937, he paid for the first FM radio station, W2XMN (later KE2XCC), in Alpine, New Jersey. This station showed that FM signals could travel far and clearly.

In 1940, the FCC decided to create a commercial FM radio service. It set aside forty channels for FM radio from 42 to 50 MHz. The first five channels were for educational stations.

After World War II, the FCC changed the FM band to higher frequencies (88 to 108 MHz). Armstrong strongly disagreed with this change. He believed it was meant to hurt FM radio and help existing AM radio companies like RCA. This change made about 395,000 FM radios bought by the public useless.

Despite this setback, people were still hopeful about FM. In 1945, Armstrong hired a public relations firm to promote FM broadcasting. Articles about Armstrong and FM appeared in popular magazines.

In 1940, RCA offered Armstrong $1,000,000 for a license to use his FM patents. He refused because he felt it was unfair to other companies that paid him royalties. This led to a long legal fight with RCA. RCA claimed it had its own FM system that didn't use Armstrong's patents. They encouraged other companies to stop paying Armstrong royalties. In 1948, Armstrong sued RCA. He believed he would win a lot of money. However, the legal battles cost him a lot of money, especially after his main patents expired in 1950.

FM Radar Research

During World War II, Armstrong also worked on FM radar for the government. He hoped that FM's ability to fight interference would increase the radar's range. He did his research at his lab in Alpine, New Jersey. The results of his studies were not clear, and the project ended when the war finished.

However, Armstrong's equipment was later used by the US Army for Project Diana. In this project, scientists successfully bounced radar signals off the moon in 1946. This was a major achievement in space communication.

Later Life and Legacy

Armstrong passed away on February 1, 1954. A friend estimated that he spent 90 percent of his time fighting legal battles against RCA.

After his death, his wife, Marion Armstrong, continued the legal cases. In 1954, RCA settled with Armstrong's estate for about $1,000,000. Marion Armstrong also won other lawsuits against companies that had used her husband's FM patents without permission. These cases lasted until 1967.

It wasn't until the 1960s that FM radio became very popular in the United States. This was helped by the development of FM stereo. Also, a new rule limited how much AM and FM stations could play the same programs. Armstrong's FM system was also used by NASA for communication with Apollo program astronauts.

In 1983, a US postage stamp was released in his honor. Armstrong has been called "the most prolific and influential inventor in radio history." His superheterodyne system is still widely used in radio equipment today. While new digital technologies are emerging, FM broadcasting remains the main system for audio broadcasting around the world.

Personal Life

Armstrong loved high places. In 1923, he climbed the antenna on top of a 20-story building in New York City. He even did a handstand up there! When asked why he did such risky things, he said, "I do it because the spirit moves me." He had photos taken and sent them to Marion MacInnis, David Sarnoff's secretary. Armstrong and Marion married later that year. As a wedding gift, he built her the world's first portable superheterodyne radio.

He enjoyed playing tennis until an injury in 1940. He was described as a very traditional person in his politics.

After Armstrong's death, Marion Armstrong founded the Armstrong Memorial Research Foundation in 1955. She worked with it until she passed away in 1979.

Honors and Recognition

In 1917, Armstrong was the first person to receive the IEEE Medal of Honor. The French government gave him the Legion of Honor in 1919 for his work during the war. He also received the Franklin Medal in 1941 and the Edison Medal in 1942. The ITU (International Telecommunication Union) added him to its list of great electricity inventors in 1955.

He received two honorary doctorates, one from Columbia in 1929 and another from Muhlenberg College in 1941.

In 1980, he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. He also appeared on a U.S. postage stamp in 1983. In 2000, he was inducted into the Consumer Electronics Hall of Fame. In 2001, he was posthumously inducted into the Wireless Hall of Fame. Columbia University created a special professorship in his memory.

Philosophy Hall at Columbia, where he invented FM radio, was named a National Historic Landmark. Armstrong's childhood home in Yonkers, New York, was also recognized as a National Historic Landmark. However, this recognition was removed when the house was torn down.

Armstrong Hall at Columbia University is named after him. It is now home to the Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Another Armstrong Hall is located at the United States Army Communications and Electronics Headquarters in Maryland.

Images for kids

Patents

Here are some of the patents Edwin H. Armstrong held:

- U.S. Patent 2,630,497 : "Frequency Modulation Multiplex System"

- U.S. Patent 2,602,885 : "Radio Signaling"

- U.S. Patent 2,540,643 : "Frequency-Modulated Carrier Signal Receiver"

- U.S. Patent 2,323,698 : "Frequency Modulation Signaling System"

- U.S. Patent 2,318,137 : "Means for Receiving Radio Signals"

- U.S. Patent 2,315,308 : "Method and Means for Transmitting Frequency Modulated Signals"

- U.S. Patent 2,295,323 : "Current Limiting Device"

- U.S. Patent 2,290,159 : "Frequency Modulation System"

- U.S. Patent 2,276,008 : "Radio Rebroadcasting System"

- U.S. Patent 2,275,486 : "Means and Method for Relaying Frequency Modulated Signals"

- U.S. Patent 2,264,608 : "Means and Method for Relaying Frequency Modulated Signals"

- U.S. Patent 2,215,284 : "Frequency Modulation Signaling System"

- U.S. Patent 2,203,712 : "Radio Transmitting System"

- U.S. Patent 2,169,212 : "Radio Transmitting System"

- U.S. Patent 2,130,172 : "Radio Transmitting System"

- U.S. Patent 2,122,401 : "Frequency Changing System"

- U.S. Patent 2,116,502 : "Radio Receiving System"

- U.S. Patent 2,116,501 : "Radio Receiving System"

- U.S. Patent 2,104,012 : "Multiplex Radio Signaling System"

- U.S. Patent 2,104,011 : "Radio Signaling System"

- U.S. Patent 2,098,698 : "Radio Transmitting System"

- U.S. Patent 2,085,940 : "Phase Control System"

- U.S. Patent 2,082,935 : "Radio Signaling System"

- U.S. Patent 2,063,074 : "Radio Transmitting System"

- U.S. Patent 2,024,138 : "Radio Signaling System"

- U.S. Patent 1,941,447 : "Radio Telephone Signaling"

- U.S. Patent 1,941,069 : "Radiosignaling"

- U.S. Patent 1,941,068 : "Radiosignaling"

- U.S. Patent 1,941,067 : "Radio Broadcasting and Receiving System"

- U.S. Patent 1,941,066 : "Radio Signaling System"

- U.S. Patent 1,716,573 : "Wave Signaling System"

- U.S. Patent 1,675,323 : "Wave Signaling System"

- U.S. Patent 1,611,848 : "Wireless Receiving System for Continuous Wave"

- U.S. Patent 1,545,724 : "Wave Signaling System"

- U.S. Patent 1,541,780 : "Wave Signaling System"

- U.S. Patent 1,539,822 : "Wave Signaling System"

- U.S. Patent 1,539,821 : "Wave Signaling System"

- U.S. Patent 1,539,820 : "Wave Signaling System"

- U.S. Patent 1,424,065 : "Signaling System"

- U.S. Patent 1,416,061 : "Radioreceiving System Having High Selectivity"

- U.S. Patent 1,415,845 : "Selectively Opposing Impedance to Received Electrical Oscillations"

- U.S. Patent 1,388,441 : "Multiple Antenna for Electrical Wave Transmission"

- U.S. Patent 1,342,885 : "Method of Receiving High Frequency Oscillation"

- U.S. Patent 1,336,378 : "Antenna with Distributed Positive Resistance"

- U.S. Patent 1,334,165 : "Electric Wave Transmission" (Note: Co-patentee with Mihajlo Pupin)

- U.S. Patent 1,113,149 : "Wireless Receiving System"

U.S. Patent and Trademark Office Database Search

The following patents were issued to Armstrong's estate after his death:

- U.S. Patent 2,738,502 : "Radio detection and ranging systems" 1956

- U.S. Patent 2,773,125 : "Multiplex frequency modulation transmitter" 1956

- U.S. Patent 2,835,803 : "Linear detector for subcarrier frequency modulated waves" 1958

- U.S. Patent 2,871,292 : "Noise reduction in phase shift modulation" 1959

- U.S. Patent 2,879,335 : "Stabilized multiple frequency modulation receiver" 1959

See also

In Spanish: Edwin Armstrong para niños

In Spanish: Edwin Armstrong para niños

- Awards named after E. H. Armstrong

- Grid-leak detector