Emergency Alert System facts for kids

The Emergency Alert System logo as of December 3, 2007

|

|

| Type | Emergency warning system |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Broadcast area | Varies; nationwide for national activation, limited to 31 counties (and equivalents) or states at a time for regional activation |

The Emergency Alert System (EAS) is a special warning system in the United States. It helps officials send important emergency messages to people. These messages go out through TV (cable, satellite, and regular broadcast) and radio (AM, FM, and satellite).

Sometimes, people confuse EAS with Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA), which sends messages to cell phones. But EAS and WEA are part of a bigger system called Integrated Public Alert and Warning System (IPAWS). This system helps federal, state, and local groups send alerts quickly using many different ways.

The EAS started on January 1, 1997. It took the place of an older system called the Emergency Broadcast System (EBS). A key part of EAS is a special digital sound called Specific Area Message Encoding (SAME). This is the "screeching" or "chirping" sound you hear at the start and end of an alert. The first sound (the "header") tells you what kind of alert it is and where it's happening. The last sound marks the end. Special machines read these sounds, helping alerts reach only the right areas.

The EAS is mainly set up so the President of the United States can talk to the whole country during a big emergency. But this has never actually happened. News channels often cover big events right away, making the system less needed for national messages. Instead, EAS is often used for local emergencies. This includes severe weather like flash floods and tornadoes, AMBER Alerts for missing children, and other local dangers.

Three main groups work together to run the EAS: the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The FCC sets the rules for how EAS works. All TV and radio stations, plus cable and satellite TV providers, must be part of this system.

Contents

How Do Emergency Alerts Work?

EAS messages have four parts. First, there's a digital code called a Specific Area Message Encoding (SAME) header. Then, an attention signal plays. After that, you hear the actual emergency message. Finally, there's a digital end-of-message marker.

The SAME header is very important. It tells you who sent the alert (like the President, state, or local officials, or the National Weather Service), what the emergency is (like a tornado or flood), and which areas are affected (up to 32 counties or states). It also says how long the alert is expected to last, when it was sent, and which station sent it.

There are 77 special radio stations called Primary Entry Point (PEP) stations. These stations are set up to send messages from the President to other TV and radio stations and cable systems.

A National Emergency Message is a notice that the President will send a message using the EAS. The government says the system can let the President speak to the country within 10 minutes during a national emergency.

What Are Primary Entry Point Stations?

The National Public Warning System, also known as Primary Entry Point (PEP) stations, is a group of 77 radio stations. These stations work with FEMA to send emergency alerts to the public before, during, and after disasters. PEP stations have extra communication gear and backup power. This helps them keep broadcasting even when other systems might fail.

Since 2016, FEMA has been building special shelters at some PEP stations. These shelters have broadcasting equipment, emergency supplies, and systems to protect against chemical, biological, or radiation threats. They are designed to help these stations keep working in almost any situation.

How Do Alerts Spread?

The FEMA National Radio System (FNARS) helps PEP stations send messages. It also acts as a direct link for the President to the EAS. The main control center for FNARS is at the Mount Weather Emergency Operations Center.

Once a PEP station sends a message, it "daisy chains" through other stations. This means one station gets the message and then sends it to many others. This creates many paths for the message to travel. This makes it more likely that everyone will get the message. Each EAS station must listen to at least two other stations for alerts.

What Do the EAS Sounds Mean?

The SAME header, which is the digital code, is sent three times. This is to make sure it's received correctly. EAS machines compare the three headers to avoid errors. If two headers match, the machine knows it's a real alert. It then decides if the message is for its local area.

After the SAME header, you hear the EAS attention tone. This tone lasts between 8 and 25 seconds. On NOAA Weather Radio stations, it's a special weather alert tone. On regular TV and radio stations, it's two high-pitched sounds (853 Hz and 960 Hz). These tones were chosen because they are loud and get your attention. Many people find them startling or unpleasant, which is exactly why they work! After the tones, you hear the voice message with the alert details.

The message ends with three quick bursts of a digital "End of Message" (EOM) signal. This signal tells the machines that the alert is over.

What is IPAWS?

In 2006, the U.S. government decided to create a better, more reliable public warning system. This led to the growth of the PEP network and the creation of the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System (IPAWS). IPAWS collects and sends alert information using the internet. It can send alerts to EAS stations, mobile phones (Wireless Emergency Alerts), and other platforms.

Even though IPAWS uses the internet, the FCC says it's not a full replacement for the older SAME system. This is because the internet might not always be available. So, stations must still change IPAWS messages into the older SAME format. This ensures alerts can still be sent using the "daisy chain" method as a backup.

What Do Stations Need to Do?

The FCC requires all TV and radio stations, and cable/satellite providers (called "EAS participants"), to have special EAS machines. These machines constantly listen for alerts from other nearby stations. To be safe, each participant must listen to at least two other stations. One of these must be a special "local primary" station.

By law, EAS participants must immediately send out National Emergency Messages (EAN) from the President. For other alerts, like severe weather or AMBER Alerts, stations can choose whether to relay them. However, TV stations with local news often interrupt their regular shows to provide full coverage of important events like severe weather.

Stations must keep records of all messages they receive. These records can be printed out or stored digitally.

How Are EAS Tests Done?

All EAS equipment must be tested every week. This is called a Required Weekly Test (RWT). It usually just includes the header and end-of-message tones. Stations often add a voice message saying it's a test, but they don't have to. RWTs are done on random days and times and are usually not sent to other stations.

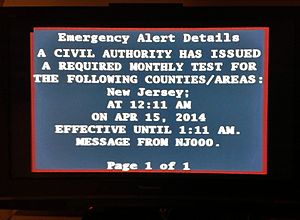

Required Monthly Tests (RMTs) are usually started by a local or state station, an emergency agency, or the National Weather Service. Then, other stations and cable channels relay them. RMTs have specific times they must be done. They must be retransmitted within 60 minutes of being received. RMTs are not done during very important events like presidential speeches, major elections, or big sports events like the Super Bowl.

If an RMT happens in a week, a RWT is not needed. Also, if a real alert happens that week, no tests are needed.

In 2018, after a false missile alert in Hawaii (caused by human error during a drill), the FCC decided to make changes. They want to prevent false alarms and allow "live code" tests. These tests would be like real emergencies to practice responses. They also allow EAS tones to be used in public service announcements to teach people about the system.

What Are Nationwide Tests?

The FCC also plans national EAS tests. These tests involve all TV and radio stations, and all cable and satellite services in the U.S. They are not sent on the NOAA Weather Radio network. The first national test was on November 9, 2011.

After the first test, the FCC found that some stations had problems. Many didn't get or retransmit the alerts correctly. To avoid confusion, future national tests are now called "National Periodic Test" ("NPT") and say "United States" as the location.

The fourth NPT happened on October 3, 2018. It was also the first time a wireless emergency alert test was sent to cell phones. The most recent NPT happened on October 4, 2023, and included both TV/radio alerts and WEA alerts on cell phones.

New Ideas for EAS

The number of different alert types in the EAS has grown to eighty. At first, most alerts were about weather. But now, many non-weather emergencies have been added. This includes the AMBER Alert System for child abductions. In 2016, new weather codes were added for hurricane events, like Extreme Wind Warning and Storm Surge Warning.

In 2004, the FCC started asking for ideas on how to make EAS better. One idea was to send mandatory text messages to cell phones. This led to the development of IPAWS, which can send alerts to mobile phones.

In 2020, Congress passed the READI Act. This law helps make wireless alerts better. It also asks the FCC to look into using EAS on internet services.

What Are the Limits of EAS?

The EAS can only send audio messages that stop all other programming. The main idea of a National Emergency Message is to be a "last resort" if the President can't reach the media. But today, news channels provide constant coverage of big events, like the September 11 attacks. This makes the EAS less necessary for such events. After the 9/11 attacks, the FCC chairman said that the widespread media coverage made using EAS unnecessary.

One challenge is that alerts can't always update in real-time. Weather events, for example, can change quickly. This means warnings might be very short, as seen in a 2019 tornado outbreak where people only had a nine-minute warning.

Also, more and more people are "cord cutting," meaning they watch streaming services instead of traditional TV. This raises concerns that people might miss emergency information if they don't watch broadcast media. The READI Act is looking into how to send alerts through internet platforms.

What About False Alarms and Hacks?

Sometimes, mistakes happen, and false alarms are sent out.

- In 2005, an alert mistakenly called for the evacuation of all of Connecticut. It was caused by human error during a test.

- In 2018, Hawaii Emergency Management Agency accidentally sent a false missile alert. This happened during a shift change.

EAS equipment has also been targeted by hackers. This usually happens when stations don't change default passwords or update their software.

- In 2013, hackers broke into EAS equipment in Montana and Michigan. They played a false alert about a "zombie apocalypse." This happened because stations didn't change their factory passwords.

- In 2020, a provider in Washington state was hacked. False alerts were sent, including a "Radiological Hazard Warning."

Why Can't EAS Tones Be Used Everywhere?

The FCC does not allow the use of real or fake EAS tones in regular TV shows, movies, ads, or other programs. This rule is in place to protect the system's importance and prevent false alarms. If broadcasters misuse the tones, they can be fined.

- In 2014, cable providers were fined for using EAS tones in a movie trailer.

- In 2015, a radio company was fined $1 million for playing a recording of a national test on a radio show.

- In 2019, several companies, including ABC and AMC Networks, were fined for using EAS or WEA tones in their shows or ads.

However, the FCC has allowed the tones to be used in some public service announcements that teach people about the Wireless Emergency Alerts system.

What About Testing Errors?

Sometimes, even during tests, things can go wrong.

- In 2008, a station accidentally started a monthly test instead of a weekly one. The operator then stopped the test too early, causing other stations to broadcast the first station's regular programming.

- During the first National EAS Test in 2011, some people reported missing visuals or audio. One satellite TV provider even played a pop song instead of the alert.

- In 2016, a test alert in New York mistakenly included a quote from a Dr. Seuss book. This was due to a mistake in how a test server was set up.

Images for kids

See also

- Alert Ready (Canada's similar system)

- Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA)

- NOAA Weather Radio

- Specific Area Message Encoding

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |