Encarnación Cabré facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Encarnación Cabré

|

|

|---|---|

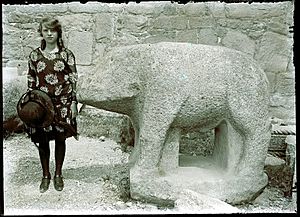

1931 passport photograph

|

|

| Born |

Encarnación Cabré Herreros

March 21, 1911 Madrid, Spain

|

| Died | March 18, 2005 (aged 93) Madrid, Spain

|

| Alma mater | Complutense University of Madrid |

Encarnación Cabré Herreros (born March 21, 1911 – died March 18, 2005) was a famous Spanish archaeologist. She studied ancient things like pottery and tools to learn about the past.

Encarnación loved archaeology from a young age. She often went with her father, Juan Cabré, who was also a well-known archaeologist. They explored many ancient sites in peninsular Spain. In the 1930s, she became a very active researcher. She wrote about her discoveries and shared them at big meetings around the world.

After the Spanish Civil War, she faced difficulties. The government at the time did not allow her to teach. So, she mostly stopped her work for a while. But in 1975, she returned to archaeology and continued her passion for the rest of her life.

Many people see Encarnación Cabré as the first woman in Spain to become a professional archaeologist. In 2019, the Spanish parliament honored her. They recognized her important work in helping women succeed in professional careers.

Contents

Who Was Encarnación Cabré?

Early Life and Discoveries

Encarnación Cabré Herreros was born on March 21, 1911, in Madrid, Spain. Her family was middle-class and very religious. Her father, Juan Cabré, was a leading Spanish archaeologist.

For her first six years, Encarnación lived with her grandparents. This was because her father's work meant he traveled a lot. He could not own a house at that time.

In 1917, her family moved to Madrid. Her father wanted to study Iberian culture at the Center for Historical Studies. Encarnación went to school at the Colegio de Monjas del Sagrado Corazón. Later, in 1921, she started at the Instituto Cardenal Cisneros. There, she studied for her high school diploma until 1928.

Also in 1921, she had her first experience at an archaeological dig. She visited Cantabria, where her father was looking at ancient sites. This trip sparked her interest in the past.

Her Journey as an Archaeologist

Encarnación started helping her father with his fieldwork in 1927. She was seventeen years old. She joined him on many digs across peninsular Spain. This continued through her university years and until the Spanish Civil War. They even wrote reports about their findings together.

From 1928 to 1932, she studied at the Complutense University of Madrid. She earned a degree in history. In 1929, she attended a big meeting in Barcelona. She presented a study there, which was the only one by a Spanish woman. She also went to another international meeting in Portugal in 1930. That same year, newspapers in Portugal and France featured her picture. They talked about how modern Spanish women were becoming.

Cabré taught as a professor at the University of Madrid. She also taught in Germany and Morocco. Around 1933, she took part in a special trip. It was a Mediterranean cruise for university students and teachers.

However, after the Spanish Civil War, the new government (the Francoist dictatorship) stopped her from teaching. Encarnación was also the only woman to start a PhD in archaeology in the early 1900s. She got a scholarship to study prehistory and ethnography in Germany in 1934 and 1935. She learned from famous German scholars there. From 1934 to 1936, she traveled in Europe. This was part of a learning program from the Spanish government.

From 1937 to 1939, Cabré finished her PhD studies. She worked with archaeologist Manuel Gómez-Moreno Martínez. Her research was about Iron Age weapons found in the Iberian Peninsula. In 1939, she had to stop working in archaeology because of family duties. She married Francisco Morán. After that, she only published a few things, mostly with her father.

After her father passed away in 1947, she returned to the field. She worked mainly to publish his research. She put his findings in different journals and conference papers from 1949 to 1959.

Later Years and Contributions

Encarnación Cabré started publishing her own work again in 1975. She often worked with her son, Juan Morán Cabré. She continued her research until she passed away on March 18, 2005, in Madrid. After her death, her family gave her and her father's old papers and records to the Autonomous University of Madrid. This way, future students could learn from their work.

Her Lasting Impact

Archaeologist María Luisa Oliveros Rives noted that in the early 1900s, women rarely worked in archaeology. They were often seen as "disruptive" at dig sites. But Encarnación Cabré was different. She was an exception because her father introduced her to the field. She worked closely with him on many important projects.

In 2018, a political group suggested renaming a garden at Madrid's National Archaeological Museum. They wanted to call it the Jardín de Encarnación Cabré. This was to honor her and other young women. These women helped open up universities to many others. They showed that women could succeed in fields usually dominated by men. On February 27, 2019, this idea was approved by the Spanish parliament.

See also

In Spanish: Encarnación Cabré para niños

In Spanish: Encarnación Cabré para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |