Ergative–absolutive alignment facts for kids

Have you ever noticed how different languages put their words together? Some languages have a special way of organizing sentences called ergative–absolutive alignment. It's a bit like a secret code for how words like "who did what" and "who got what" are treated.

Imagine you have two types of actions:

- Action 1: Someone does something by themselves, like "She walks." (This is called an intransitive verb because the action doesn't go to another person or thing).

- Action 2: Someone does something to someone or something else, like "She finds it." (This is called a transitive verb because the action "transfers" to an object).

In ergative-absolutive languages, the person doing Action 1 ("She walks") is treated grammatically the same as the thing that Action 2 happens to ("it" in "She finds it"). But the person doing Action 2 ("She" in "She finds it") is treated differently.

This is different from English! In English, the person doing Action 1 ("She walks") is treated the same as the person doing Action 2 ("She finds it"). Both are called the "subject." The thing Action 2 happens to ("it" in "She finds it") is called the "object" and is treated differently.

Languages like Basque, Georgian, and many Mayan languages use this ergative-absolutive system. It's a fascinating way to see how languages can be built!

Contents

Ergative vs. Accusative Languages

Let's break down the main differences between ergative and accusative languages.

How Subjects and Objects are Treated

In an ergative language, the word for the "object" of a transitive verb (the thing the action happens to) and the "subject" of an intransitive verb (the one doing an action by themselves) are treated the same. This could mean they have the same word ending or are placed in the same spot in a sentence. The "agent" (the one doing the action in a transitive verb) is treated differently.

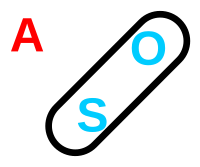

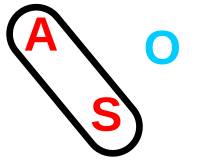

Think of it like this:

- S = The single person/thing doing an action (like "She" in "She walks").

- A = The person/thing doing an action to someone/something else (like "She" in "She finds it").

- O = The person/thing that the action happens to (like "it" in "She finds it").

In ergative languages, S and O are grouped together.

Now, in nominative–accusative languages like English, the S (the one doing an action by themselves) and the A (the one doing an action to someone else) are treated the same. They are both called the "subject." The O (the one the action happens to) is treated differently.

So, in English, S and A are grouped together.

Grammatical Cases

Many languages use grammatical cases to show a word's role. These are often special endings added to words.

- In ergative-absolutive languages:

* The A (the agent of a transitive verb) gets the ergative case. * The S (the subject of an intransitive verb) and the O (the object of a transitive verb) both get the absolutive case.

- In nominative-accusative languages (like English, though English doesn't use many case endings anymore):

* The S (the subject of an intransitive verb) and the A (the agent of a transitive verb) both get the nominative case. * The O (the object of a transitive verb) gets the accusative case.

Here's a simple table to show the difference:

| Ergative–Absolutive | Nominative–Accusative | |

|---|---|---|

| A (Agent) | ERGATIVE | NOMINATIVE |

| O (Object) | ABSOLUTIVE | ACCUSATIVE |

| S (Single Subject) | ABSOLUTIVE | NOMINATIVE |

How Ergativity Shows Up

Ergativity can appear in two main ways: in the morphology (how words are formed) or in the syntax (how sentences are built).

Morphological Ergativity

This is when a language uses special word endings or forms to show ergativity.

For example, in Basque, the word for "Martin" changes depending on its role:

| Ergative Language Example (Basque) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sentence: | Martin etorri da. | Martinek Diego ikusi du. | ||||

| Word: | Martin-Ø | etorri da | Martin-ek | Diego-Ø | ikusi du | |

| Gloss: | Martin-ABS | has arrived | Martin-ERG | Diego-ABS | has seen | |

| Function: | S | VERBintrans | A | O | VERBtrans | |

| Translation: | "Martin has arrived." | "Martin has seen Diego." | ||||

Notice how "Martin" has no ending (-Ø) when he "has arrived" (S). But when "Martin" "has seen Diego" (A), he gets the ending -ek. "Diego" (O) also has no ending (-Ø). This shows that S and O are treated the same (absolutive), and A is treated differently (ergative).

Now compare this to Japanese, which is a nominative-accusative language:

| Accusative Language Example (Japanese) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sentence: | 男の人が着いた Otokonohito ga tsuita. | 男の人がこどもを見た Otokonohito ga kodomo o mita. | ||||

| Words: | otokonohito ga | tsuita | otokonohito ga | kodomo o | mita | |

| Gloss: | man NOM | arrived | man NOM | child ACC | saw | |

| Function: | S | VERBintrans | A | O | VERBtrans | |

| Translation: | "The man arrived." | "The man saw the child." | ||||

Here, "otokonohito" (man) gets the particle ga whether he "arrived" (S) or "saw the child" (A). But "kodomo" (child), the object (O), gets the particle o. This shows that S and A are treated the same (nominative), and O is treated differently (accusative).

Syntactic Ergativity

This is when ergativity shows up in how sentences are structured, like word order or how clauses are linked. It's much rarer than morphological ergativity.

For example, in the Dyirbal language from Australia, if you have two sentences joined together, the way you can shorten them depends on whether the language is ergative or accusative.

In English (accusative), you can say: "Father returned and ____ saw mother." (The blank means "father" is understood). This works because "father" is the subject (S) in the first part and the subject (A) in the second part.

In Dyirbal (ergative), you can say: "Father returned and ____ was seen by mother." (The blank means "father" is understood). This works because "father" is the subject (S) in the first part and the object (O) in the second part. You couldn't say "Father returned and ____ saw mother" in Dyirbal if "father" was the agent (A) in the second part.

This shows how the "pivot" (the main role that words can take) is different in ergative languages.

Split Ergativity

Many languages don't use ergativity all the time. They might use it only in certain situations, like with specific types of verbs or in certain tenses. This is called split ergativity.

For example:

- In Hindustani (Hindi and Urdu), ergativity often appears when talking about actions that are already finished (the "perfective aspect").

- In Georgian, ergativity is used for completed actions in the past.

- In Kurmanji (a Kurdish language), ergativity is used for past tense actions, but not for present or future actions.

Optional Ergativity

Sometimes, ergative marking isn't always used, even when it could be. This is called optional ergativity. It's not truly "optional" though! The choice often depends on things like:

- How "alive" or "active" the subject is (e.g., a person vs. a rock).

- The type of verb (e.g., a very active verb vs. a less active one).

- The sentence structure.

This can be found in languages from Australia, New Guinea, and Tibet.

Where are Ergative Languages Found?

Ergative languages are found in specific parts of the world. They are common in:

- The Caucasus region (like Georgian, Chechen)

- The Americas (many Native American languages like Mayan and Eskimo–Aleut languages)

- The Tibetan Plateau (Tibetan)

- Australia (most Australian Aboriginal languages, like Dyirbal)

- Parts of New Guinea

Some examples of specific ergative languages or language families include:

- Americas: Mayan languages, Eskimo–Aleut languages, Salish languages

- Asia: Tibetan, Pashto, Burushaski

- Australia: Most Australian Aboriginal languages

- Europe: Basque

- Caucasus and Near East: Georgian, Chechen, Kurdish

Approximations of Ergativity in English

Even though English is mostly a nominative-accusative language, it has some interesting features that are a bit like ergativity!

The "-ee" Suffix

Think about words ending in "-ee":

- "John has retired" → "John is a retiree" (John is the one doing the action).

- "Susie employs Mike" → "Mike is an employee" (Mike is the one the action happens to).

Notice how "-ee" can mean the person doing an action (like "retiree") or the person receiving an action (like "employee"). This is similar to how ergative languages treat the S and O roles.

Nominalizations

When you turn a sentence into a noun phrase, English sometimes uses "of" or the possessive case for the S and O roles, but "by" for the A role.

- "The water boiled" (S) → "The boiling of the water"

- "A dentist extracts a tooth" (A extracts O) → "The extraction of a tooth by a dentist"

Here, "the water" (S) and "a tooth" (O) are grouped together with "of," while "a dentist" (A) is marked differently with "by." This is another small way English shows a pattern similar to ergativity.

See also

In Spanish: Lengua ergativa para niños

In Spanish: Lengua ergativa para niños

- Absolutive case

- Ergative case

- Split ergativity

- Transitivity (grammar)