Field (mathematics) facts for kids

In mathematics, a field is a special kind of collection of numbers where you can do addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. These operations work just like they do with the numbers you already know, like rational numbers (fractions).

Fields are a very important idea in algebra, number theory, and many other parts of mathematics. They help us understand how different number systems behave.

Some of the most famous fields are:

- The field of rational numbers (all fractions).

- The field of real numbers (all numbers on the number line).

- The field of complex numbers (numbers like a + bi).

Many other fields exist, like those used in algebraic geometry and cryptography. For example, the math behind fields helped prove that some ancient Greek geometry problems, like dividing an angle into three equal parts using only a compass and straightedge, are impossible.

Fields are also the foundation for linear algebra, which is used to solve systems of equations. They are also key in number theory for studying properties of numbers, and in error correction codes to fix mistakes in data.

Contents

What is a Field?

Imagine a set of numbers where you can always add, subtract, multiply, and divide (except by zero!) and always get another number within that same set. That's basically what a field is!

For example, if you take any two rational numbers (fractions), you can add, subtract, multiply, or divide them, and your answer will always be another rational number. This means rational numbers form a field.

The Rules of a Field

To be a field, a set of numbers (let's call it F) must follow these rules for addition (+) and multiplication (⋅):

- Associativity: When you add or multiply three numbers, the way you group them doesn't change the answer.

* a + (b + c) = (a + b) + c * a ⋅ (b ⋅ c) = (a ⋅ b) ⋅ c

- Commutativity: The order of numbers doesn't matter for addition or multiplication.

* a + b = b + a * a ⋅ b = b ⋅ a

- Identities: There are special numbers:

* A zero (0) such that a + 0 = a. * A one (1) such that a ⋅ 1 = a. * And 0 and 1 must be different!

- Inverses:

* For every number a, there's an additive inverse (written as −a) such that a + (−a) = 0. * For every number a (except 0), there's a multiplicative inverse (written as a−1 or 1/a) such that a ⋅ a−1 = 1.

- Distributivity: Multiplication spreads over addition.

* a ⋅ (b + c) = (a ⋅ b) + (a ⋅ c)

These rules make sure that the operations in a field behave in a predictable and useful way.

Examples of Fields

Rational Numbers

Rational numbers are numbers that can be written as a fraction a/b, where a and b are integers, and b is not zero.

- The additive inverse of a/b is −a/b.

- The multiplicative inverse of a/b (if a is not zero) is b/a.

All the field rules work for rational numbers, which is why they are a great example of a field.

Real and Complex Numbers

The real numbers (like 3, -5.2, or √2) also form a field. You can do all four basic operations with real numbers and always get another real number.

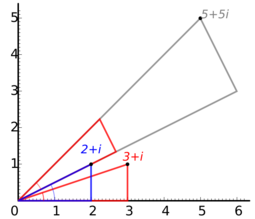

Complex numbers are numbers that look like a + bi, where a and b are real numbers, and i is a special number where i2 = −1. Complex numbers also form a field. They are used a lot in science and engineering. You can imagine complex numbers as points on a flat surface, and multiplication can be seen as rotating and stretching these points.

Constructible Numbers

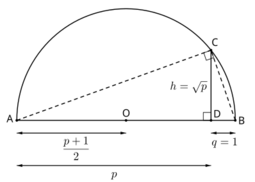

In ancient times, mathematicians wondered which numbers could be "constructed" (drawn) using only a compass and a straightedge. These are called constructible numbers.

These numbers form a field! You can add, subtract, multiply, and divide constructible numbers, and the result will always be another constructible number. For example, you can construct the square root of a constructible number, as shown in the picture.

However, not all numbers are constructible. For instance, it's impossible to construct a cube with double the volume of another cube using only a compass and straightedge.

A Field with Four Elements

Fields don't have to be infinite like rational or real numbers. There are also finite fields, which have a limited number of elements.

Here's an example of a field with just four elements: O, I, A, and B. O acts like 0 (the additive identity). I acts like 1 (the multiplicative identity).

| Addition | Multiplication | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

You can check the field rules using these tables. For example, from the addition table, A + B = I. From the multiplication table, A ⋅ B = I.

This field is called F4 or GF(4). The smaller set {O, I} (highlighted in blue) is also a field, called the binary field F2. It's the smallest possible field!

Basic Ideas About Fields

Important Consequences

- If you multiply any number a by 0, the answer is always 0: a ⋅ 0 = 0.

- If you multiply two numbers a and b and the answer is 0 (a ⋅ b = 0), then either a must be 0 or b must be 0 (or both). This is a very useful property!

Groups Within a Field

A field has two important "groups":

- The additive group includes all elements of the field under addition.

- The multiplicative group includes all elements of the field except zero under multiplication.

These groups help mathematicians understand the structure of fields even better.

Field Characteristic

The characteristic of a field tells you something special about its addition. If you keep adding the number 1 to itself (1 + 1 + 1 + ...), one of two things will happen:

- It will never equal 0. In this case, the field has characteristic 0. The rational numbers and real numbers are examples of fields with characteristic 0.

- It will eventually equal 0. The smallest number of times you have to add 1 to itself to get 0 is always a prime number. This prime number is the field's characteristic. For example, in the field F4, I + I = O (which is like 1 + 1 = 0), so its characteristic is 2.

Subfields and Prime Fields

A subfield is a smaller field that is completely contained within a larger field. For example, the rational numbers are a subfield of the real numbers.

Every field contains a smallest possible subfield, called its prime field.

- If a field has characteristic 0, its prime field is like the rational numbers.

- If a field has characteristic p (a prime number), its prime field is like the finite field Fp (which we'll talk about next).

Finite Fields

Finite fields are fields that have a limited number of elements. They are also called Galois fields. We saw an example with F4, which has four elements. The smallest finite field is F2, with just two elements (0 and 1).

You can create simple finite fields using modular arithmetic. This is like doing math on a clock. For example, "modulo 5" means you only use the numbers {0, 1, 2, 3, 4}. If you add 3 + 4, you get 7, but in modulo 5, 7 is 2 (because 7 divided by 5 leaves a remainder of 2).

A set of numbers {0, 1, ..., n-1} with modular arithmetic forms a field only if n is a prime number.

- For example, if n = 5, you get the field F5.

- If n = 4, it's not a field because 2 ⋅ 2 = 4, which is 0 in modulo 4. But in a field, if two non-zero numbers multiply to 0, that's not allowed!

Every finite field has q elements, where q is a power of a prime number (like 22=4, or 33=27). All finite fields with the same number of elements are essentially the same (mathematicians say they are "isomorphic").

History of Fields

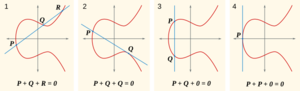

The idea of fields grew from mathematicians trying to solve polynomial equations (like x2 + 2x + 1 = 0).

- In the 1700s, Joseph-Louis Lagrange noticed patterns in how solutions to equations behaved. This work later connected to the idea of fields and groups.

- Carl Friedrich Gauss studied equations like xp = 1 in the early 1800s. His work showed how to construct regular polygons using a compass and straightedge, which involved early ideas of fields.

- Later, Niels Henrik Abel and Évariste Galois proved that some polynomial equations (like those with x5) cannot be solved using simple formulas involving roots. Their work laid the foundation for Galois theory, which uses fields to understand these problems.

- The actual word "field" (or "Körper" in German, meaning "body") was introduced by Richard Dedekind in 1871. He described it as a system of numbers closed under the four basic operations.

- Heinrich Martin Weber gave the first clear definition of an abstract field in 1893, including finite fields.

- Over time, mathematicians like Ernst Steinitz and Emil Artin further developed the theory of fields, making it a central part of modern algebra.

Building New Fields

Making Fields from Rings

A commutative ring is like a field, but it doesn't require every non-zero element to have a multiplicative inverse. For example, integers (..., -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, ...) form a commutative ring. You can add, subtract, and multiply integers, but you can't always divide and get an integer (e.g., 1/2 is not an integer).

There are ways to turn a ring into a field:

Field of Fractions

You can create a field of fractions from a ring, just like you create rational numbers from integers. You take elements from the ring and form fractions with them. For example, the field of fractions of the integers is the rational numbers.

Residue Fields

You can also create a field by using polynomials. For example, to get the complex numbers from the real numbers, you can think of it as adding the imaginary unit i, which satisfies the equation i2 + 1 = 0. This process creates a new field where that equation now has a solution.

Field Extensions

A field extension is when you start with a field (let's call it E) and create a larger field (let's call it F) that contains E. We write this as F / E.

For example, the complex numbers C are an extension of the real numbers R.

Algebraic Extensions

An element x in a larger field F is called algebraic over a smaller field E if it is a solution to a polynomial equation whose coefficients are in E. For example, the imaginary unit i is algebraic over the real numbers because it solves x2 + 1 = 0.

An algebraic extension is a field extension where every element in the larger field is algebraic over the smaller field.

Algebraic Closure

A field is algebraically closed if every polynomial equation with coefficients from that field has a solution within that same field.

- The complex numbers C are algebraically closed. This means any polynomial equation with complex coefficients has a complex solution.

- The rational numbers Q and real numbers R are not algebraically closed because x2 + 1 = 0 has no rational or real solution.

Every field has an algebraic closure, which is the smallest algebraically closed field that contains it. For example, the complex numbers are the algebraic closure of the real numbers.

Fields with Special Properties

Ordered Fields

An ordered field is a field where you can compare any two elements (say if x is greater than or equal to y). The real numbers are an ordered field with their usual way of comparing numbers.

Topological Fields

A topological field is a field where the numbers also have a sense of "distance" between them, and all the field operations (addition, multiplication, etc.) work smoothly with this distance. For example, the real numbers are a topological field where the distance between two numbers is their absolute difference.

Applications of Fields

Solving Equations (Linear Algebra)

In a field, if you have an equation like ax = b (where a is not 0), there's always one unique solution for x. This simple fact is super important in linear algebra, which is used to solve many equations at once. It's the basis for methods like Gaussian elimination.

Secure Codes (Cryptography)

Finite fields are crucial for modern cryptography (making secure codes). Many encryption methods rely on calculations in large finite fields, where some operations are easy to do, but their reverse operations are very hard. This makes codes difficult to break. Elliptic curve cryptography is one example that uses finite fields.

Describing Shapes (Geometry)

In geometry, especially algebraic geometry, fields of functions are used to describe properties of geometric shapes. For example, the "function field" of a shape can tell you about its dimension or other important features.

Studying Numbers (Number Theory)

Fields are central to number theory. Global fields are special fields (like number fields, which are extensions of rational numbers, or function fields over finite fields) that are studied in depth. They help mathematicians understand deep properties of numbers. For example, cyclotomic fields were used to prove Fermat's Last Theorem (about xn + yn = zn).

Related Ideas

Division Rings

A division ring (sometimes called a skew field) is almost a field, but it doesn't require multiplication to be commutative (meaning a ⋅ b might not always equal b ⋅ a). The most famous example of a division ring that is not a field is the quaternions (H).

Interestingly, a theorem called Wedderburn's little theorem states that any finite division ring must actually be a field! So, if a division ring has a limited number of elements, its multiplication must be commutative after all.

See also

In Spanish: Cuerpo (matemáticas) para niños

In Spanish: Cuerpo (matemáticas) para niños