Fork (software development) facts for kids

In the world of software development, a fork happens when someone takes a copy of an existing computer program's source code. They then start working on this copy separately from the original program. Imagine you have a recipe, and someone makes a copy of it. They might change some ingredients or steps, making a new version of the dish.

At first, the new program (the fork) works exactly like the original. But as people make more changes to the copied code, the new program starts to behave differently. It's like a road that splits into two paths. A fork is a type of "branching," but it usually means the new files are stored in a different place, not just a different part of the same project.

People might create a fork for several reasons. Maybe they prefer a different way for the software to work. Sometimes, the original software stops being updated or developed. Or, there might be disagreements among the people who create the software.

It's important to know that you can't just fork any software. If software is "proprietary" (meaning someone owns the copyright), you usually need special permission. But "free and open-source software" is different. By its very nature, you can legally fork it without asking for permission.

Contents

What Does "Fork" Mean?

The word "fork" has meant "to divide into branches" or "go separate ways" for a very long time, since the 1300s.

In computer programming, people started using "fork" in the 1980s. It described making a new "branch" or version of a program. For example, Eric Allman used it in 1980 to say that creating a branch "forks off" a version of the program.

By 1983, the term was used online to describe creating a new discussion group. This new group would move specific topics of conversation away from a main one.

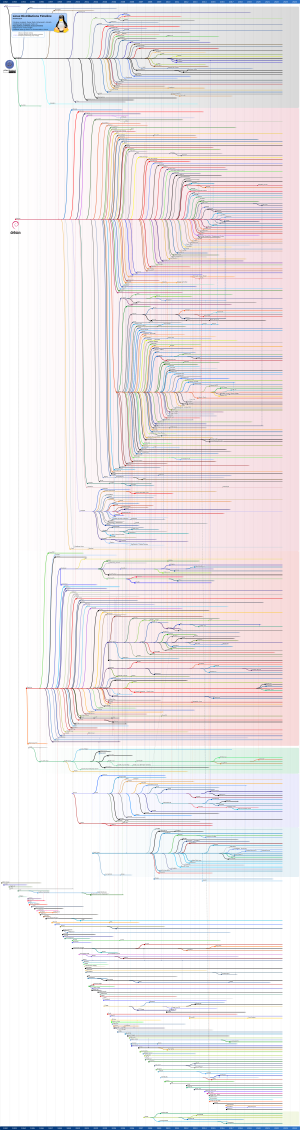

Later, in the 1990s, "fork" started being used to describe when a group of software developers split up. This happened with projects like XEmacs and the Berkeley Software Distribution (BSDs). By 1995, "fork" was a common way to talk about these kinds of splits in the GNU Project.

The word is also used for a special computer command called fork(). This command makes a running computer program split into two. This allows both parts to do different tasks at the same time.

Forking Free and Open-Source Software

Free and open-source software (often called FOSS) can be legally forked. This means you don't need permission from the original developers. This is a key part of both The Free Software Definition and The Open Source Definition. These definitions say you have the freedom to share copies of your changed versions. This lets everyone benefit from your improvements. To do this, you must have access to the program's source code.

In free software, forks often happen because people have different goals for the project. Sometimes, it's because of disagreements between developers. When a fork happens, both groups usually start with almost the same code. However, the larger group, or the one that controls the main website, often keeps the original name. They also keep the original community of users. This means that starting a fork can sometimes make a project lose some of its good reputation.

The relationship between the different teams can be friendly or not so friendly. A "friendly fork" or "soft fork" is different. This kind of fork doesn't want to compete. Instead, it aims to combine its changes back into the original project later.

Eric S. Raymond, a well-known writer about open source, said that a fork creates "competing projects." These projects cannot easily share code later, which can divide the people working on them. He also noted that forking is often seen as a "Bad Thing." This is because it can waste effort and cause arguments between the groups. Because of this, big forks are rare. People remember them in the history of computer programming.

David A. Wheeler, another expert, described four things that can happen after a fork:

- The fork dies: This is the most common outcome. It's easy to start a fork, but it takes a lot of work to keep developing it separately.

- The fork joins back with the original: Sometimes, the new version becomes the main one. For example, egcs became the new version of GNU Compiler Collection.

- The original project dies: The new fork becomes more successful. For example, the X.Org Server took over from XFree86.

- Successful branching: Both the original and the fork continue to exist. They often become different from each other. Examples include OpenBSD and NetBSD.

Tools like Git and Mercurial have made the idea of "forking" less dramatic. With these tools, it's normal to make a personal copy (a "fork") of a project's code. You then work on your changes separately. Later, you might try to add your changes back to the main project. Websites like GitHub and Bitbucket make it easy to host these independent copies. This has made it much simpler to "fork" a project. GitHub even uses "fork" as the term for this way of contributing to a project.

When software is forked, the new project often restarts its version numbers. It might start from 0.0.1, 0.1, or 1.0. This happens even if the original software was at a much higher version like 3.0 or 5.0. An exception is made if the forked software is meant to directly replace the original. For example, MariaDB is a fork of MySQL, and LibreOffice is a fork of OpenOffice.org.

Some special licenses, like the BSD licenses, allow forks to become "proprietary software." This means the software can be owned by a company and not be open for everyone to use freely. Some people who support "copyleft" licenses (which ensure software stays free) worry that this will happen often. However, copyleft licenses can sometimes be worked around. Companies might offer a special agreement that allows proprietary use.

Examples of forks that became proprietary include macOS (which is based on FreeBSD) and Cedega and CrossOver (which are proprietary forks of Wine). Some companies that create these proprietary forks contribute their changes back to the original open-source project. Others keep their changes secret to gain a business advantage.

Forking Proprietary Software

In the case of proprietary software, a company usually owns the copyright. The individual programmers don't own it. So, proprietary code is more often forked when the owner needs to create different versions. For example, they might need a version that works with windows on a screen. Or, they might need a version that uses only command line text. They might also create versions for different operating systems, like a word processor for IBM PC computers and Macintosh computers.

These internal forks usually aim to look and feel the same. They also use the same data formats and behave similarly across different platforms. This way, a user who knows one version can easily use another. They can also share documents created on different versions. This decision is almost always made for business reasons. It helps the company reach more customers. This helps them earn back the extra money spent on developing the different versions.

A famous example of proprietary forks is the many types of Unix. Almost all of them came from AT&T Unix under special agreements. They were all called "Unix," but they became more and more different from each other. This led to what is known as the Unix wars.

See also

In Spanish: Bifurcación (desarrollo de software) para niños

In Spanish: Bifurcación (desarrollo de software) para niños

- Custom software

- Downstream (software development)

- Duplicate code

- Group decision-making

- List of software forks

- Modding

- Modular programming

- Personalization

- ROM Hacking

- Source port

- Team effectiveness