Francoist Catalonia facts for kids

Francoism in Catalonia was a period in Catalonia's history from 1939 to 1975. It began after the Spanish Civil War when Francisco Franco's government took control. This time was very different from the earlier period when Catalonia had more freedom.

Franco's rule was a dictatorship, meaning one person had all the power. In Catalonia, this meant losing democratic freedoms. The government also tried to stop people from using the Catalan language and celebrating Catalan culture. The goal was to make everyone in Spain follow one culture and speak only Castilian Spanish.

During Franco's rule, political parties were banned, except for his own. Newspapers could not print freely. The special rules that gave Catalonia some self-government were removed. The Catalan language was not allowed in public places like schools or government offices.

Many people died in the Civil War. After the war, more people were executed, like President Lluís Companys. Many others had to leave the country and live in exile. Those who stayed faced prison or were not allowed to work in certain jobs. This made life very hard for them. Some small groups, called the maquis, fought against the government in secret. One famous action was their attempt to take over the Val d'Aran.

In the 1960s, Spain's economy started to grow. Farming became more modern, industries expanded, and many tourists visited. Catalonia also saw many people move there from other parts of Spain. This made cities like Barcelona grow quickly. During this time, groups against Franco's rule became stronger, especially workers' groups like the Commissions Obreres.

By the 1970s, different groups wanting democracy joined together in the Assembly of Catalonia. Franco died on November 20, 1975. This opened the way for Spain to become a democracy again.

Contents

Harsh Treatment of Catalans

Catalonia faced some of the toughest times during the Civil War. Many people in Franco's government showed strong dislike for Catalans. For example, a priest in Tarragona in 1939 called Catalans "dogs" who were "not worthy of the sun."

Franco himself said that his soldiers who entered Barcelona felt the most "hatred towards Catalonia and Catalans." Some of his close friends even suggested that Catalonia should be punished severely. They saw Catalan identity as a "disease" or a "cancer" that needed to be removed.

Even some Catalan conservatives, like Francesc Cambó, were worried by Franco's strong hatred. Cambó wrote in his diary that Franco seemed to care only about his victory. He thought Franco was like a bullfighter, just wanting applause and gifts.

Lluís Companys, who was the president of Catalonia, went into exile in France in 1939. However, he was captured by German forces in 1940 and sent back to Spain. He faced a quick trial without proper legal steps. On October 15, 1940, he was executed at Montjuïc Castle. Many people still ask for his trial to be officially cancelled today.

Franco's Repression

After the repression, the Franco regime created networks of complicity in which thousands of people were involved or were accomplices, in all possible ways, of the bloodshed inflicted, of the persecutions carried out, of the lives of hundreds of thousands people in prisons, concentration camps or Battalions workers. In short, the most diverse forms of repression: political, social, labor, ideological, and in the case of Catalonia, in an attempt of cultural genocide that sought to do away with its specific national personality...

—Josep Maria Solé i Sabaté i Joan Vilarroya i Font

Franco's government punished many people. Thousands were involved in or supported the violence. Hundreds of thousands were put in prisons or forced labor camps. This punishment was political, social, and aimed at controlling people's thoughts. In Catalonia, it was also an attempt to destroy Catalan culture and identity.

Some thinkers at the time believed in ideas about "improving" the Spanish "race." They thought certain groups, like Catalans, were "degenerate." They linked Catalan identity to communism and separatism. This thinking led to the harsh treatment of Catalans. One rebel leader even said their plan was to "exterminate a third of the Spanish male population." Franco himself said the war was to "save the Homeland" from "racial degeneration."

This way of thinking led to very strong repression in Catalonia. The attacks on Catalan culture lasted throughout Franco's rule. It became a main part of how the government controlled the region.

Banning the Catalan Language

During Franco's rule (1939–1975), not only were democratic freedoms taken away, but the Catalan language was also suppressed. It was removed from schools and could only be used at home. Castilian Spanish became the only language for education, government, and media.

Experts say that until 1951, the persecution of Catalan was "total." In some schools, students had to report classmates who spoke Catalan. The language was even banned from gravestones.

After Nazi Germany was defeated in 1945, Franco's government tried to improve its image. This allowed some Catalan cultural activities to return. For example, the Orfeó Català could perform in Catalan. Some classic Catalan books could be published. However, books for young people were still banned to stop them from learning to read and write in Catalan.

Later, the government became a bit more open. In 1964, the first Catalan TV program aired. The Nova Cançó (New Song) movement started in 1961, using Catalan music to express feelings. In 1971, the Assembly of Catalonia was formed, uniting groups against Franco. All these efforts kept the Catalan language alive. However, there were still limits, like the ban on Joan Manuel Serrat singing in Catalan at Eurovision in 1968.

In the 1960s and 70s, many Spanish speakers moved to Catalonia, especially to Barcelona. This led to Spanish becoming the most common first language in Catalonia for the first time.

Despite the bans, people found ways to keep Catalan alive. Books and magazines were published secretly. Theater groups performed in Catalan. Franco had declared in 1939 that he wanted "only one language, Spanish, and a single personality, Spanish." This led to almost no books being printed in Catalan until 1946.

However, some books were still published. In 1941, a book of poems was reissued illegally. Later, young writers like Carles Riba and Salvador Espriu published their works, though in very small numbers. In 1947, the Institut d'Estudis Catalans managed to publish a scientific book in Catalan. This showed that Catalan was also a language for science. The important Catalan-Valencian-Balearic Dictionary was completed in 1962. Its author, Francesc de Borja Moll, worked hard to defend the unity of the language.

Catalans Who Supported Franco

Not all Catalans were against Franco. Some intellectuals, like painters, writers, and journalists, supported his government. In return, they received approval and favors. Many of them had been part of the conservative Lliga Regionalista political party. Famous examples include Salvador Dalí, Josep Pla, and Juan Antonio Samaranch.

In 1936, the artist André Breton removed Dalí from his surrealist group because of Dalí's support for fascism. Dalí was one of the few intellectuals who backed Franco after the Civil War. In 1949, Dalí returned to Catalonia with Franco's approval. The government used his return for political propaganda, which many artists and thinkers criticized.

Josep Pla was a moderate Catalan writer. He returned to Barcelona in 1939 with other pro-Franco journalists. He took over the editing of the newspaper La Vanguardia.

Juan Antonio Samaranch joined Franco's party when he was young. He started his political career in Barcelona's City Council in 1955. He held several important positions under Franco. Later, he became the president of the International Olympic Committee (1980–2001). He received many honors, but also faced criticism for his unclear position regarding Franco's rule.

Some mayors in Catalonia also supported Franco. Josep Maria de Porcioles was the mayor of Barcelona for a long time. His time as mayor saw a lot of uncontrolled building in the city. Another mayor, Josep Gomis i Martí of Montblanc, had a long career in politics, serving as mayor for 16 years.

Even FC Barcelona had presidents who agreed with Franco's government. Narcís de Carreras was one of them. He was president of FC Barcelona from 1968 to 1969. In contrast, Josep Sunyol, another FC Barcelona president and a strong supporter of the Republic, was shot by Franco's troops in 1936 without a trial.

A Decade of Repression

Between 1953 and 1963, the dictatorship continued its harsh rule. People were arrested, faced unfair trials, imprisoned, and even killed for fighting for freedom. Even before a big religious event in Barcelona in 1952, five people were executed. Laws against political opponents remained in force for years.

During this decade, the maquis, or secret fighters, slowly disappeared. The government set up a strong police and court system to stop workers' protests. They also controlled and censored books, theater, movies, and education. The system included government officials, police, and special courts like the Court of Public Order (TOP). This court was not dissolved until 1977.

Barcelona Tram Strike

In 1951, people in Barcelona went on a tram strike. The main reason was that tram ticket prices went up, and they were more expensive than in Madrid. But the strike also showed how unhappy people were with the difficult living conditions after the Civil War. Not taking the tram was not a crime, which made it hard for the government to stop.

The strike lasted two weeks and was a big moment for those opposing Franco. Many different groups of people joined the protest. The governor of Barcelona tried to use the police, which led to some deaths. Finally, the governor and mayor were removed, and the price increase was cancelled. This strike showed the power of peaceful protest. A similar strike happened in 1957, lasting 12 days, with support from many intellectuals.

Maquis Fighters

The maquis were groups of fighters who hid in forests or mountains. They fought against the German occupation in France during World War II. In Spain, the Spanish Maquis were armed groups who fought against Franco's government after the Civil War. They were active in areas like the Pyrenees and Catalonia.

After France was freed from German forces in 1944, the maquis in Catalonia increased their actions. They attacked a beer factory and tried to invade the Val d'Aran in October 1944. About 2,500 fighters entered the valley, hoping to take over Spanish territory. They wanted to force other countries to help free Spain from Franco. But they were defeated, and after this, the Communists stopped this type of fight.

Death of the Last Catalan Maquis

The last two famous Catalan maquis were Quico Sabaté and Ramon Vila Caracremada.

Quico Sabaté was a very important maquis leader. After being in prison in France, he returned to Spain in December 1959 with four friends. They were spotted by the police and a shootout happened. Quico Sabaté was injured, and his friends were killed. Despite his injuries, he reached the town of Sant Celoni, where he was killed after fighting hard. He became a legend.

Ramon Vila Caracremada continued fighting until 1963. After damaging some power towers, he was surrounded by the police. He was shot and killed on August 6, 1963, at an abandoned farmhouse. He was buried without a marker in a cemetery.

University Protests

In 1969, about 500 students at the University of Barcelona protested by taking over the Rector's office. The police quickly surrounded them. The civil governor ordered the police to arrest and fine the students. This was a new level of police action since 1939. Student groups, especially leftist ones like the PSUC, grew stronger during this time.

The Sixties and Seventies

In the 1960s, more and more people in Spain openly disagreed with Franco's rule. The government found it hard to control this growing opposition. Too much repression made the government look bad. But being too tolerant made them seem weak. The situation became more complicated. Traditional opposition groups, like Communists, now worked with others, even Catholics. Also, Spain wanted to join the European Economic Community, so the government had to be careful not to use too much force.

Being jailed for political reasons became a source of pride for many. Losing freedom to defend it was seen as an honor. In 1958, a new law allowed workers and employers to negotiate. This was a big change in Franco's Spain, where workers' rights had been suppressed. People also saw a new "consumer society" emerging. Things like televisions, washing machines, and cars became available to more people. This economic growth changed Catalonia a lot.

Festival at the Palau de la Música

A famous event happened on May 19, 1960, at the Palau de la Música Catalana. It was a tribute to a Catalan poet. The program was supposed to include the song Cant de la Senyera, which is a Catalan anthem. But three days before, the civil governor banned the song. This made the audience very angry. Josep Espar started singing it, and then the police attacked the singers and activists.

Jordi Pujol, who later became the President of Catalonia, was arrested for helping organize the event. He was sentenced to seven years in prison. Years later, Pujol said that this event was the first victory for Catalans against Franco's government.

New State of Emergency

The government declared a "state of emergency" several times. One reason given was a "conspiracy" by 118 opponents of the regime who met in Munich. This state of emergency allowed the government to deal with strikes, the growth of the ETA group, and student protests. The dictatorship showed its harshest side during these times. These emergency measures continued until Franco died.

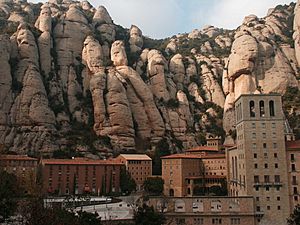

Abbot Escarré's Exile

Aureli Maria Escarré, the abbot of the Montserrat monastery, supported Catalan culture. He became more and more critical of Franco's government. In 1963, he told a French newspaper that there was no real freedom or justice in Spain. He said people should choose their own government and that the regime stopped Catalan culture from growing. He also said that Spain had not had "twenty-five years of peace" but "twenty-five years of victory" for one side, which was not Christian.

Franco's government was very angry. They pressured the Vatican to make Abbot Escarré leave the monastery. On March 12, 1965, Abbot Escarré went into exile.

Nova Cançó Movement

The Nova Cançó (New Song) movement was very important in Francoist Spain. It broke the silence imposed on the Catalan language and culture. It started with an article in 1959 that said, "we need songs from now."

Early singers performed Catalan versions of international hits, but censorship often forced them to sing in Spanish. In 1961, a group called Els Setze Jutges (The Sixteen Judges) was formed. They sang in Catalan, and the movement grew. Famous singers like Joan Manuel Serrat and Lluís Llach joined later.

La Caputxinada

In the mid-1960s, students at the University of Barcelona wanted to form a democratic student union. On March 9, 1966, over 500 students, teachers, and intellectuals met at the Sarrià Capuchins convent. This event became known as "La Caputxinada" because of the Capuchin fathers who allowed them to use their hall.

Famous people like Salvador Espriu and Antoni Tàpies were there. They quickly approved their plans for a democratic university. The police arrived and ordered them to leave, but the union had already been formed.

Meeting of Intellectuals at Montserrat

From December 12–14, 1970, about 300 Catalan intellectuals met at the Santa Maria de Montserrat Abbey. This meeting was a protest against the trial of ETA members in Burgos. Writers, singers, journalists, and artists gathered for three days, even though the police threatened to raid the abbey.

They discussed the country's situation and future. They formed a permanent group of Catalan intellectuals. They also wrote a statement asking for political freedom, forgiveness for political prisoners, and the right for Catalonia to decide its own future. This meeting had a big impact internationally. The government punished the participants with fines and travel bans, but the international attention helped to change some death sentences.

Assembly of Catalonia

The Assembly of Catalonia was created on November 7, 1971, in Barcelona. It brought together many political parties, unions, and social groups against Franco's rule. Their main goals were:

- To gain democratic rights and freedoms.

- For people to have economic power.

- For people to have political power.

- To fully exercise the right to self-determination (for Catalonia to decide its own future).

In the 1970s, the Assembly of Catalonia was the main group organizing resistance against the dictatorship. It led many large public protests.

Iberian Liberation Movement

The Movimiento Ibérico de Liberación (MIL) was a small, armed group active in Barcelona and France between 1971 and 1973. It became well-known after one of its members, Salvador Puig Antich, was executed by Franco's government in March 1974. Another member, Oriol Solé Sugranyes, was shot during an escape in 1976.

Catalans saw Puig Antich's execution as a symbol of the fight for Catalonia's self-rule. He became a very famous name in Barcelona as one of Franco's last victims. Other groups formed to get revenge for his death.

End of Francoism

After Franco died, the signs of his rule quickly disappeared in Catalonia. Street names like "Francisco Franco Avenue" were changed. The first national law to address the crimes of Francoism came in 2007.

In 2015, an organization called Òmnium Cultural held an event to condemn the crimes of Francoism and honor its victims. This event was supported by the Catalan government and the City Council of Barcelona.

See also

In Spanish: Dictadura franquista en Cataluña para niños

In Spanish: Dictadura franquista en Cataluña para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |