Spanish Maquis facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Spanish Maquis |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War and World War II | |||||||

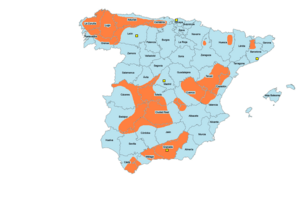

Principal areas of Maquis activity within Spain (orange), 1939–1965. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Supported by: (1939–1945) (1939–1943) (after 1953) |

Supported by: |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

among others… |

|||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~1,000+ killed | 5,548 total 2,166 killed 3,382 captured or arrested |

||||||

The Maquis (pronounced MAH-kees) were Spanish freedom fighters. They used guerrilla tactics, which means they fought in small groups using surprise attacks. They fought against the government of Francisco Franco in Spain after the Spanish Civil War ended in 1939. Their fight continued until the early 1960s.

These groups carried out secret missions like sabotage (damaging things to disrupt the enemy), robberies (to get money for their fight), and sometimes assassinations of people they believed supported Franco. They also played a big part in fighting against Nazi Germany and the Vichy government in France during World War II.

The Maquis were most active around 1946. However, they faced strong attacks from Franco's government between 1947 and 1949. Many fighters and their supporters were killed or arrested. The movement slowly faded away and finally ended in the 1960s.

Contents

What the Maquis Did

The Spanish Maquis were very brave. They helped the French Resistance during World War II. A writer named Martha Gellhorn wrote about their actions in 1945:

- They sabotaged over 400 railway lines.

- They destroyed 58 trains and 35 railway bridges.

- They cut 150 telephone lines.

- They attacked 20 factories and damaged 15 coal mines.

- They captured thousands of German soldiers.

- They even captured three tanks, which was amazing because they had limited weapons.

- In southwestern France, they freed more than 17 towns.

During World War II, Spanish fighters also helped in important missions against German officers. In October 1944, about 6,000 Maquis fighters tried to invade Spain through the Aran Valley. They were pushed back after ten days.

Not many details about the Maquis' actions in Spain were made public. This was because Franco's government kept things secret. But we know that guerrillas like Francesc Sabaté Llopart, Jose Castro Veiga, and Ramon Vila Capdevila were responsible for many acts of sabotage. They also caused the deaths of hundreds of Civil Guard officers. Between 1943 and 1952, the Civil Guard arrested 2,166 Maquis members. This greatly weakened the movement.

Where the Name "Maquis" Comes From

The word maquis comes from the French word maquis. This word originally came from the Corsican language, macchia. It refers to a type of dense shrubland or bush found in Mediterranean areas, especially on the island of Corsica.

In France, the term was first used for groups of French Resistance fighters. These groups hid in the countryside to fight against the German occupation during World War II. The fighters themselves were called maquisards.

History of the Maquis

The Maquis movement started in 1936. Many people fled to the mountains to escape Franco's forces during the Spanish Civil War. They were called huidos, meaning "those who've fled." Most of these early groups were quickly defeated. Only those in the northern parts of Spain managed to survive the war.

When World War II began, many Spanish Republicans who had fled to France joined the French Resistance. By 1944, as German forces were losing ground, many of these fighters decided to focus their efforts on Spain again. Even though their invasion of the Val d'Arán failed that year, some groups managed to enter Spain. They connected with other groups who had been hiding in the mountains since 1939.

The Maquis' actions were strongest between 1945 and 1947. After this, Franco's government increased its efforts to stop them. One by one, the Maquis groups were destroyed. Many members were killed or put in prison. Others escaped back to France or Morocco. By 1952, most of the remaining groups left Spain. Only a few fighters stayed behind, fighting just to survive in the forests and mountains.

How the Maquis Began

The Maquis started with people who ran away from Franco's advancing army. Franco's harsh methods made many political opponents, and even those who just supported the Republic, become fugitives. At first, many hid in their relatives' homes. But some sought safety in the mountains. Their numbers grew with soldiers who deserted and people who escaped from prisons. These individuals formed the core of those who decided to keep fighting from hidden places.

The Maquis groups included people with different political beliefs. There were communists, socialists, and anarchists. Despite these differences, the Communist Party of Spain played a big role in organizing them until 1948.

The XIV Guerrilla Army Corps

During the Spanish Civil War, some leaders thought about fighting Franco's forces from behind their lines. This idea led to the creation of the XIV Guerrilla Army Corps in October 1937. This group aimed to cut off Franco's supply lines and carry out special missions. If the main Republican army lost, they planned to continue the fight.

By the end of the war, this Corps was active in several areas of Spain. One important action was freeing 300 political prisoners in Granada in May 1938. However, when the Republicans lost the war, the Corps was disbanded.

Life in French Camps

After the Spanish Civil War, hundreds of thousands of Spanish soldiers and civilians crossed into France. French authorities placed them in large camps. There were 22 such camps in France and North Africa. In these camps, the Spanish exiles began to organize themselves into guerrilla groups.

In one camp, Argelès-sur-Mer, meetings were held. In October 1940, they decided to join the French Resistance. They would fight against the Vichy government, which cooperated with Nazi Germany. This marked the start of a large Spanish involvement in fighting the German occupation of France.

Joining the Resistance

In October 1940, the Vichy government started the "Companies of Foreign Workers." This allowed prisoners to leave the camps if they worked in factories. This gave many a chance to escape. Soon after, the Vichy government also created the "Obligatory Work Service" for French citizens. This forced them to work in factories or build defenses.

French people who were forced into this service began to escape to the forests and mountains. There, they met up with Spanish escapees. These French escapees were mostly civilians, not soldiers. This is when the French term "maquis" started being used for the hidden camps, and "maquisards" for the fighters.

Forming the AGE

Some Spanish refugees joined French resistance groups. Others formed their own groups. In April 1942, several Spanish combat groups met. They decided to call themselves the "XIV Cuerpo del Ejército de Guerrilleros Españoles" (XIV Corps of Spanish Guerrilla Army). They saw themselves as continuing the fight.

In May 1944, this group changed its name to "Agrupación de Guerrilleros Españoles" (AGE), meaning "Spanish Guerrilla Group." This was because most of its fighters were Spanish. By this time, Spanish fighters had taken part in many battles against the German army. They even helped free several towns in southern France.

The number of Spanish fighters in the Resistance is estimated to be around 10,000. After the German army was pushed out of France, the Spanish Maquis turned their attention back to Spain.

The Invasion of Val d'Aran

The most famous operation by the Spanish Maquis was an invasion of Spain. Between 4,000 and 7,000 guerrillas entered Spain through the Val d'Aran and other parts of the Pyrenees mountains. This happened on October 19, 1944, after the German army had left southern France. This invasion was called "Operation Reconquest of Spain."

The AGE planned this operation. They created the 204th Division, made up of 12 brigades, led by Vicente López Tovar. Their goal was to take back a part of Spanish land near the French border. They hoped the Spanish Republican government in exile would then declare this area free. This was meant to cause a general uprising against Franco across Spain. They also hoped it would make the Allied forces "liberate" Spain, just as they were freeing the rest of Europe.

The main attack in Val d'Aran was supported by smaller attacks in other Pyrenees valleys. These were meant to distract Franco's forces and gather information. The main entry points were Roncesvalles, Roncal, Hecho, Canfranc, Val d'Aran, Andorra, and Cerdanya.

Franco's forces quickly moved a large number of troops to the area. These included the Civil Guard, police, Spanish Army battalions, and 40,000 Moroccan troops. The Maquis managed to capture several towns and villages. They raised the Spanish Republican flag and held anti-Franco meetings. They also controlled part of the French border for several days, bringing in supplies. However, they failed to capture Vielha e Mijaran, their main target.

Overwhelmed by Franco's superior numbers and equipment, the guerrillas had to retreat. The retreat ended on October 28, when the last fighters crossed back into France. The hoped-for uprising in Spain did not happen.

Guerrilla Groups in Spain

Even after the failure in Arán in 1944, the exiled Spanish Communist Party (PCE) still had high hopes. They believed that with fascism collapsing in Europe, change in Spain was still possible. Across Spain, guerrilla activity increased. New fighters came from France, and groups became more organized like military units.

The PCE encouraged the creation of "Agrupaciones Guerrilleras" (Guerrilla Groups) in different areas. These groups worked together. One of the most active was the "Agrupación Guerrillera de Levante y Aragón (AGLA)." This group operated in the areas of Teruel, Castellón, and Cuenca. Another notable group was the "Stalingrad Group," led by "Manolo el Rubio," which operated near Cádiz.

These groups were very strict and followed the orders of the PCE leaders. Fighters who wanted to leave and return to normal life were often treated as deserters and even shot.

In 1948, the PCE changed its plan. Following advice from Stalin, they stopped supporting the guerrilla fight. They decided to try to change the Spanish government from within. This led to the decline of the "Agrupaciones." They were already weakened by government crackdowns. The groups renamed themselves "Resistance Committees." However, this new approach was not effective. By 1952, a general evacuation of fighters from Spain was ordered.

The End of the Maquis

Several things led to the end of the Spanish Maquis. First, the start of the Cold War made it clear that the Allies would not help the Maquis fight Franco. This caused the PCE to stop supporting the guerrilla groups in the 1950s.

Franco's government kept the Maquis' actions a secret. Outside the areas where the Maquis were active, most people knew nothing about them. When the press did mention them, they were called "bandoleros" (bandits). This was to make their actions seem like crimes, not political resistance.

Franco's forces slowly isolated the guerrillas. By 1950, most fighters were middle-aged or older. Years of living outdoors and lacking proper food and medicine weakened them. In these final years, many tried to escape to France. Those who stayed in Spain faced harsh fates. Some were jailed for many years. Others were quickly judged and shot. Many died at the hands of the Civil Guard, often under the "Ley de Fugas" (law of fugitives), which allowed them to be killed while supposedly trying to escape.

Although the main period of Maquis activity was from 1938 to the early 1950s, some groups continued to fight. The very end of the movement is marked by the deaths of Francisco Sabate Llopart (El Quico) in 1960, Ramon Vila "Caracremada" in 1963, and Xosé Castro Veiga in March 1965.

Areas Where the Maquis Fought

The Maquis mostly operated in mountainous areas across Spain. They preferred forests or places with thick plants that offered shelter and cover. Another important factor for their survival was local support. They needed to be in areas where at least some people would help them. Without local support, it was very hard for a guerrilla group to survive.

In areas with harsh weather, like the mountains of León, the Maquis would often hide in small groups in villagers' homes, especially during winter.

Major areas of Maquis activity included:

- The Cantabrian Coast: From Galicia to Cantabria, especially the mountains of Lugo, Asturias, and northern León.

- The Iberian System: Specifically the area between Teruel, Castellón, Valencia, and Cuenca.

- Central Spain: Including Extremadura, northern Cordova, Ciudad Real, Toledo, and the mountains of the Sistema Central.

- Two separate areas in southern Andalusia: Cádiz and the Granada-Málaga region.

- There was also activity in other places like La Mancha and High Aragon.

Armed resistance groups were also active in cities, mainly in Madrid, Barcelona, Málaga, and Granada. In Madrid, the Maquis were mostly communists. But their activities did not last long. In Barcelona, the Maquis were mainly anarchists. This city was the last urban place to see Maquis activity. Attempts to spread the fight to other cities like Valencia and Bilbao were not successful.

The Maquis mostly fought in rural and isolated areas. This made it hard for them to achieve their goals. Because the press and government kept silent, very few people outside these areas knew about the conflict. Most of the Spanish population was unaware of a guerrilla war happening in their mountains.

The "Enlaces" (Links)

To keep fighting, the Maquis relied on people called "enlaces" (pronounced en-LAH-ses). This word means "links" or "connections." There were also "passive militias" and "guerrillas of the plains." These people provided help, from food and weapons to information. They also delivered mail for the groups.

The enlaces were at high risk of being caught by the government. However, they also became a source of new fighters. If they were discovered, their only way to avoid jail was to flee to the mountains and join the Maquis. Because of this, even in the early 1950s, when the Maquis were almost defeated, new men and women were still joining.

The number of enlaces was much higher than the number of actual fighters. During the years of guerrilla activity, about 20,000 people were arrested for helping the Maquis.

Famous Maquis Fighters

- Benigno Andrade, known as "Foucellas," was a Maqui from Galicia. He fought against the Civil Guard in Corunna Province. He was arrested in 1952 and executed later that year.

- Felipe Matarranz González, known as "El Lobo," and Manuel Zapico, known as "El asturiano," were Asturian Maquis.

- Cristino García Granda was another important Asturian Maqui.

- Joaquín Arasanz Raso, known as "Villacampa" and "el maqui," was active in Aragón.

- In Catalonia, the group of Francesc Sabaté Llopart, "El Quico," operated in cities like Barcelona. The group of Marcelino Massana, along with Ramon Vila Capdevila (also known as "Caraquemada"), mainly operated in the Catalan regions of Berguedà, Osona, and Bages.

- Josep Lluís i Facerias, known as "Face," and his group robbed banks. They used the money to support the families of people jailed by Franco's government.

- Casimiro Fernández Arias led a group of former Republican soldiers. They hid for nine years in the Cantabrian mountains.

- Manuel Girón Bazán, known as "Girón," was a Maqui from León. He mainly operated in Bierzo.

- Pablo Pérez Hidalgo, known as "Manolo el Rubio," led groups in the mountains near Ronda and Sierra Bermeja. He was captured in 1976.

- Antonio Téllez fought in the invasion of the Val d'Aran. He later wrote books about other Maquis leaders.

- Abel Paz was jailed twice by Franco's government and wrote several books about the Spanish Civil War.

- Eduard Pons Prades was part of an anti-fascist group in France in 1942. He helped with sabotage actions.

- La Pastora, also known as Teresa, was a Maqui who sometimes disguised herself as a woman. She operated in the Maestrat area until the early 1960s.

- Xosé Castro Veiga (1915–1965) was known as the last guerrillero.

|

See also

In Spanish: Maquis (guerrilla antifranquista) para niños

In Spanish: Maquis (guerrilla antifranquista) para niños

- Armed resistance in Chile (1973–90)

- Japanese holdout

- Maquis (World War II)

- Opposition to Francoism

- Republican insurgency in Afghanistan

- Spanish National Liberation Front (FELN)

- Spanish transition to democracy (1975–82)

- Spain in World War II