History of Catalonia facts for kids

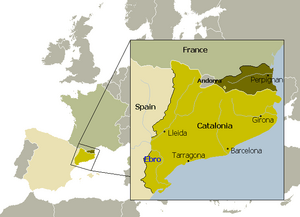

The land we now call Catalonia has a long and exciting history. It started with the Iberian people who lived there. Later, some Greek colonies were built along the coast. Then, the powerful Romans arrived and made it the first part of Hispania they conquered.

After the Roman Empire fell, the Visigoths took over. In 718, the area was conquered by the Umayyad Caliphate and became part of Muslim-ruled al-Andalus. The Frankish Empire then fought to take back the northern part. They captured Barcelona in 801. This created a Christian buffer zone against Muslim rule, known as the Marca Hispanica. By the 10th century, the County of Barcelona became more and more independent from Frankish rule.

In 1137, Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona married Petronilla, who was the future queen of Aragon. This created a union between the County of Barcelona and Aragon. This new union was later called the Crown of Aragon. The County of Barcelona and other Catalan counties joined to form a new state, the Principality of Catalonia. This state developed its own rules and systems, like the Catalan Courts and the Generalitat, which helped limit the kings' power. Catalonia helped the Crown of Aragon grow in trade and military strength, especially with its strong navy. The Catalan language also spread as more lands joined the Crown, including Valencia, the Balearic Islands, Sardinia, Sicily, Naples, and Athens. However, tough times in the late Middle Ages, the end of the House of Barcelona family, and a civil war (1462–1472) made Catalonia less powerful.

In 1469, Ferdinand II of Aragon married Isabella I of Castile. This joined the Crowns of Aragon and Castile. But both kingdoms kept their own laws, systems, borders, and money. In 1492, Spain began to explore and settle the Americas. This meant that political power started to move towards Castile. Tensions grew between Catalonia and the monarchy. Economic problems and peasant revolts led to the Reapers' War (1640–1652). For a short time, Catalonia even declared itself a republic. In 1659, the Treaty of the Pyrenees gave the northern parts of Catalonia, like Roussillon, to France. Catalonia lost its separate state status after the War of Spanish Succession (1701–1714). In this war, Catalonia supported Archduke Charles of Habsburg. After the Catalan surrender on 11 September 1714, King Philip V of Bourbon changed things. He made Spain more unified, like France. He introduced the Nueva Planta decrees, which removed Catalonia's main political systems and laws. Catalonia became a province of Castile. This also meant that Catalan was no longer used for government or important writings. But in the late 17th and 18th centuries, Catalonia's economy grew. This was helped when Cádiz's trade monopoly with American colonies ended.

In the 19th century, Catalonia faced many challenges from the Napoleonic and Carlist Wars. The Napoleonic occupation caused a lot of political and economic trouble. In the middle of the century, Catalonia became a hub for industry. As the economy grew, Catalonia also saw a cultural rebirth. This came with a rise in Catalan identity and new worker movements, especially anarchism.

In the 20th century, Catalonia gained and lost its self-rule several times. The Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939) gave Catalonia its own government and made Catalan an official language again. Like much of Spain, Catalonia fought to defend the Republic in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). The Republic's defeat led to the dictatorship of Francisco Franco. This brought harsh rule and took away Catalonia's self-rule. Spain was devastated and cut off from international trade. Catalonia, being an industrial center, suffered greatly. Economic recovery was slow. But between 1959 and 1974, Spain had a fast economic growth, known as the Spanish Miracle. Catalonia became Spain's most important industrial and tourist area. In 1975, Franco died, ending his rule. The new democratic Spanish constitution of 1978 recognized Catalonia's self-rule and language. Today, Catalonia has a lot of self-government and is one of Spain's most active economic regions. Since the 2010s, many people have been calling for Catalan independence.

Contents

- Ancient History: Early People and Roman Rule

- From Old Empires to New Kingdoms (400–1100)

- Catalonia and Aragon: A Powerful Union (1100–1469)

- Early Modern Period: Changes and Conflicts (1469–1808)

- Modern Period: Wars, Industry, and Identity (1808–1939)

- Contemporary Period: From Dictatorship to Democracy (1939–Present)

- See also

Ancient History: Early People and Roman Rule

First Humans in Catalonia

The first signs of humans in what is now Catalonia date back to the Middle Palaeolithic period. The oldest human bone found is a jawbone in Banyoles. Some say it's 200,000 years old, from before Neanderthals. Others think it's about a third of that age. Important ancient remains have been found in caves like Mollet and Cau del Duc. Remains from the Upper Paleolithic era are in places like Reclau Viver. From the next period, the Epipaleolithic or Mesolithic (8000 BC to 5000 BC), important findings include those at Sant Gregori.

The Neolithic era began in Catalonia around 4500 BC. People were slow to build fixed homes here. This was because there were many woods, allowing them to continue living as hunter-gatherers. Key Neolithic sites include the Cave of Fontmajor and the early village of La Draga.

The Copper Age (2500 to 1800 BC) saw the start of copper tools. The Bronze Age (1800 to 700 BC) has few remains. Some settlements were found near the Segre river. This period also saw the arrival of the Indo-Europeans. They started the first small towns around 1200 BC. The Iron Age began in Catalonia around the mid-7th century BC.

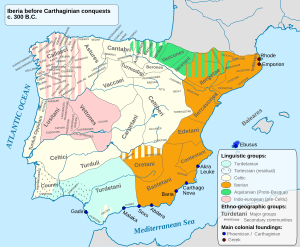

Rise of the Iberian Culture

An iron-using culture appeared in eastern Iberia in the 8th century BC. By the 5th century BC, the Iberian civilization was strong on the eastern side of the Iberian Peninsula. What is now Catalonia was home to several Iberian tribes. These included the Indigetes in Empordà and the Ceretani in Cerdanya. Important towns were Ilerda (Lleida) and Indika (Ullastret). The settlement of Castellet de Banyoles in Tivissa was a very important Iberian site. The 'Treasure of Tivissa', a collection of silver Iberian items, was found there in 1927.

Iberian society had different groups, like kings, nobles, priests, and workers. Nobles often met in a council. Kings kept their power through a system of loyalty. The Iberians learned about wine and olives from the Greeks. Horse breeding was very important for Iberian nobles. Mining was a big part of their economy. They made fine metalwork and good iron weapons.

The Iberian language was spoken in a wide coastal area. The oldest writings are from the late 5th century BC. The language was slowly replaced by Latin. Greeks arrived on the Iberian coasts in the late 7th century BC. The trading colony of Empúries was founded by the Greek city of Phocaea in the 6th century BC. It was a busy trade center. Another Greek colony was Rhode (Roses).

Roman Times: Catalonia Becomes Roman

The Romans brought a new stage to Catalonia's history. Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvus arrived in Empúries in 218 BC. His goal was to cut off supplies for Hannibal's army during the Second Punic War. After the Carthaginians were defeated, the Romans fully conquered the area that became Catalonia by 195 BC. The region then truly became Roman. The local tribes adopted Roman culture and lost their own languages. Many local leaders joined the Roman noble class.

Most of Catalonia became part of the Roman province of Hispania Citerior. After 27 BC, it became part of Tarraconensis, with its capital at Tarraco (now Tarragona). Other important Roman cities were Ilerda (Lleida) and Barcino (Barcelona). All cities gained Latin law under Vespasian (69-79 AD). All free men in the Empire got Roman citizenship in 212 AD. It was a rich farming province, growing olives, grapes, and wheat. The first centuries of the Empire saw the building of roads, like the Via Augusta, and structures like aqueducts.

The Crisis of the Third Century affected the whole Roman Empire, including Catalonia. Many Roman farms were destroyed or left empty. This period also shows the first signs of Christianity arriving. Christianity spread in cities in the 4th century. The first Christian groups in Tarraconense were formed in the 3rd century. The diocese of Tarraco was set up by 259 AD. Even though Hispania stayed under Roman rule, its main cities suffered attacks. Cities like Barcino (Barcelona) and Tarraco (Tarragona) became smaller and built defensive walls.

From Old Empires to New Kingdoms (400–1100)

Visigoths and Muslims in Catalonia

In the 5th century, Germanic tribes invaded the Roman Empire. The Visigoths, led by Athaulf, settled in Tarraconensis (410). In 475, the Visigothic king Euric formed the kingdom of Tolosa (Toulouse). This kingdom included the area of present-day Catalonia. Later, the Visigoths lost land north of the Pyrenees and moved their capital to Toledo. The Visigothic Kingdom in Hispania lasted until the early 8th century. They kept the Roman provincial system, but Tarraconense became smaller.

In 654, King Recceswinth created the Liber Iudiciorum (Book of the Judges). This was the first law code that applied to both Goths and Hispano-Romans. This law was used in Catalan counties until the Usages of Barcelona were written. Between 672 and 673, eastern Tarraconenis (modern Catalonia) rebelled against King Wamba. The rebellion was put down by Wamba.

In 714, Muslim forces reached the northeastern part of Spain. In 720, Narbonne fell to the Arab-Berber forces. The last Visigothic king, Ardo, died in battle in 721. During the time of the Caliphate of Córdoba in the 10th century, the northern border was set. It ran along the Llobregat and Cardener rivers. Lleida and Tortosa were key defense cities in the Muslim-ruled area, known as "New Catalonia." Many Christians in these border regions became Muslims. People in the Ebro, Segre, and Cinca valleys adopted Muslim ways of life. They used advanced irrigation methods. The most important Muslim cities in Catalonia were Lleida, Balaguer, and Tortosa. They had old towns (Medina) with mosques, government offices, and courts. They also had large markets with workshops. Tortosa had a military fortress. Goods were shipped from Tortosa's port. Even with peace treaties, attacks happened. In 985, Almanzor, the ruler of the Caliphate, attacked Barcelona and captured thousands of people.

The Franks and the Catalan Counties

After stopping Muslim attacks as far north as Tours in 732, the Frankish Empire created a Christian buffer zone in the south. This area became known as the Marca Hispanica. The first county taken from the Muslims was Roussillon (including Vallespir) in 759.

In 785, the County of Girona (with Besalú) was captured. Ribagorça and Pallars were added around 790. Urgell and Cerdanya were added in 798. The County of Empúries was probably under Frankish control before 800. In 801, Charlemagne's son Louis took Barcelona from the Moors. He set up the County of Barcelona.

The counts of the Marca Hispanica ruled small areas. They were loyal to the Carolingian Emperor. In the late 9th century, Charles the Bald made Wilfred the Hairy the Count of Cerdanya and Urgell (870). After Charles died, Wilfred also became Count of Barcelona and Girona (878). He brought together most of what would become Catalonia. When he died, his sons divided the counties. However, Barcelona, Girona, and Ausona stayed under the same ruler. These became the heart of the future Principality. Wilfred made his titles hereditary when he died in 897. He started the House of Barcelona family, which ruled Catalonia until 1410.

The Rise of Feudalism

During the 10th century, the counts became more independent from the weak Carolingian rulers. In 988, Borrell II, the Count of Barcelona, refused to promise loyalty to Hugh Capet, the new French king. Borrell did this because Capet didn't help him against Muslim attacks. During this time, the population of the Catalan counties started to grow. In the 9th and 10th centuries, many people were aloers. These were peasant farmers who owned small family farms. They grew food for themselves and didn't owe loyalty to a lord.

The 11th century saw the growth of feudalism. Knights and lords gained power over these independent peasants. In the middle of the century, there was a lot of fighting between social classes. Lords used new military tactics and hired armed soldiers to control the peasants. By the end of the century, most aloers had become loyal followers (vassals) of lords.

The counts' power also weakened. The Spanish Marches split into more counties. These counties slowly became a state based on complex loyalties. During the rule of Countess Ermesinde of Carcassonne, central power fell apart. But her grandson, Ramon Berenguer I, brought back strong leadership. He started writing down Catalan laws in the Usages of Barcelona. This became the first full collection of feudal law in Western Europe. The Catholic Church also tried to stop the violence with the Peace and Truce of God movement. The first meeting was in 1027. This movement created sagreres, sacred areas around churches where violence was forbidden.

Catalonia and Aragon: A Powerful Union (1100–1469)

Joining Forces with Aragon

Until the mid-12th century, the Counts of Barcelona tried to expand their lands. Ramon Berenguer III added the counties of Besalú, Empúries, and Cerdanya. He also gained the County of Provence through marriage. The Catalan church became independent from the bishopric of Narbonne in 1118.

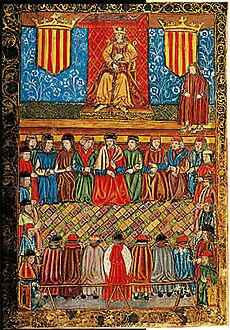

In 1137, the union that would become the Crown of Aragon was formed. Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona married Petronilla, the future queen of Aragon. This happened after Ramiro II of Aragon agreed to give his kingdom and daughter to Barcelona's Count. This protected Aragon from being invaded by Castile. Ramon Berenguer IV used the title "count of the Barcelonians" and "prince of the Aragonians." His wife kept her title of "queen." Their son, Alfonso II, became "king of Aragon, count of Barcelona, and marquis of Provence." Catalonia and Aragon kept their own laws and traditions. Catalonia kept its unique identity with one of Europe's first parliaments, the Catalan Courts.

Ramon Berenguer IV also conquered Lleida and Tortosa. This completed the unification of all the land that is now Catalonia. A new area south of the Catalan counties became known as Catalunya Nova ("New Catalonia"). It was settled by Catalans by the end of the 12th century.

Growth and Government in Catalonia

During Alfonso's rule in 1173, Catalonia was first recognized as a legal entity. The Usages of Barcelona were put together to become the law of Catalonia. Other important writings like the Liber feudorum maior and the Gesta Comitum Barchinonensium were also created. These are seen as key to Catalan identity.

Catalonia became the center of the Aragonese Crown's sea power. This power spread across the western Mediterranean. They conquered Valencia, the Balearic Islands, Sardinia, and Sicily. This led to a big increase in sea trade in Catalan ports, especially Barcelona.

In 1213, Peter II of Aragon ("Peter the Catholic") died in the Battle of Muret. This ended the plan to expand Aragonese power over Provence and Toulouse. His successor, James I of Aragon, became strong by 1227. He then started new conquests. Over the next 25 years, he conquered Majorca and Valencia. Valencia became a new kingdom with its own laws. Majorca and other northern territories became a kingdom for his son James II of Majorca. This led to conflicts until the Kingdom of Majorca was joined back to the Crown of Aragon in 1344.

In 1258, James I and Louis IX of France signed the Treaty of Corbeil. The French king gave up his claims over Catalonia. James gave up his claims in Occitania.

At the same time, the Principality of Catalonia developed a complex government system. It was based on an agreement between the king and the different groups of society. From 1283, new laws had to be approved by the General Court of Catalonia. This was the first parliament in Europe that stopped the king from making laws alone. The Courts had three groups and were led by the king as Count of Barcelona. They approved the constitutions, which set out rights for the people of Catalonia. To collect taxes, the Courts created the Generalitat in 1359. This group gained a lot of political power over the centuries.

Catalonia had a good period in the 13th and early 14th centuries. The population grew, and Catalan culture spread. The reign of Peter III of Aragon ("the Great") included conquering Sicily and defending against a French attack. His son Alfonso ("the Generous") conquered Menorca. Peter's second son James II conquered Sardinia. Barcelona became the main administrative center. The Catalan Company, a group of soldiers led by Roger de Flor, fought for the Byzantine Empire. After Roger de Flor was killed, the Company attacked Thrace and Greece. They took over the duchies of Athens and Neopatras for the King of Aragon. Catalan rule in Greece lasted until 1390.

This growth also led to a big increase in Catalan trade. Barcelona was the center, with a large trade network across the Mediterranean. This competed with Genoa and Venice. New groups like the Consulate of the Sea were created to protect merchants. The Book of the Consulate of the Sea was one of the first books of sea laws. Trade also led to banking. In 1401, Barcelona created a pioneering public bank, the Taula de canvi de Barcelona.

The mid-14th century brought big changes. There were natural disasters, population drops, and economic problems. In 1333, a severe famine hit. Between 1347 and 1497, Catalonia lost 37% of its people. The reign of Peter the Ceremonious was a time of war. These wars caused financial problems. Then, in 1410, Martin I died without an heir. This led to a two-year period without a king. Finally, Ferdinand I of Aragon from the Castilian Trastámara family was chosen in 1412. Opposition to Ferdinand was defeated in 1413.

Catalonia in the 15th Century

Ferdinand's successor, Alfonso V ("the Magnanimous"), expanded Aragon's power to the Kingdom of Naples. But he also made social problems worse in Catalonia. Political conflicts arose in Barcelona. Meanwhile, the "remença" peasants, who were like serfs, started to organize against unfair feudal rules. They sought protection from the king. Alfonso's brother, John II, was not liked by many.

Catalan institutions opposed John II's policies. They supported his son, Charles, Prince of Viana. When John arrested Charles, the Generalitat formed a council. They forced John to negotiate. The Capitulation of Vilafranca (1461) made John release Charles and name him lieutenant of Catalonia. The king needed the Generalitat's permission to enter Catalonia. This agreement made Catalonia's system of shared power stronger. However, John's disagreement, Charles's death, and a peasant uprising in 1462 led to a ten-year civil war. This war exhausted the country. In 1472, the last separate ruler of Catalonia, René of Anjou, lost the war to King John.

The peasant conflict was not fully resolved. In 1493, France returned the counties of Roussillon and Cerdagne. Ferdinand II of Aragon ("the Catholic") reformed Catalan institutions. He got back the northern Catalan counties without war. He also solved the peasant problems with the Sentencia Arbitral de Guadalupe in 1486. This ruling allowed peasants to freely make contracts for their land. This led to prosperity in the Catalan countryside for centuries. In 1481, the Catalan Courts approved the Constitució de l'Observança. This law made sure the king's power was under the laws of Catalonia.

Early Modern Period: Changes and Conflicts (1469–1808)

Joining Crowns: Aragon and Castile

Ferdinand's marriage to Isabella I of Castile in 1469 joined the Crown of Aragon with Castile. After the 1512 invasion of Navarre, the two monarchies formally united into a single Monarchy of Spain in 1516. Each part of the Monarchy kept its own political systems, laws, and money.

When Christopher Columbus discovered the Americas, Europe's trade focus shifted from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic. This reduced Catalonia's economic and political importance. Spanish expansion into the Americas was mainly a Castilian effort. Catalans, as subjects of the Crown of Aragon, could not trade directly with the Castilian-ruled Americas until 1778.

In 1516, Charles I of Spain became the first king to rule both Castile and Aragon by his own right. In 1519, he was also elected Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. In the 16th century, Catalonia's population and economy started to recover. Charles V's reign was a peaceful time. Catalonia accepted the new structure of Spain, even though it was less important. The Kingdom of Valencia became the most important part of the Aragonese Crown. The reign of Philip II marked a slow decline for Catalonia's economy, language, and culture. Piracy along the coast and banditry inland were big problems.

The Reapers' War: A Fight for Rights

Conflicts between Catalonia and the monarchy began during Philip II's time. Philip wanted to use the resources of all parts of Spain. Catalan institutions and laws were well protected and valued by the people. They had more say in their local government. When Philip IV became king in 1621, his minister, the Count-Duke of Olivares, tried to get more taxes and soldiers from all kingdoms. This went against the idea that each kingdom had its own rules. Catalonia strongly resisted, as it saw little benefit from these sacrifices. The Catalan Courts of 1626 and 1632 failed to agree with Olivares's plans. This made tensions worse.

The Reapers' War (Guerra dels Segadors, 1640–59) began with a peasant uprising in northern Catalonia. Spanish soldiers were stationed in Roussillon for the war with France. Peasants had to house and feed them, causing much anger. There were reports of soldiers destroying property and harming local women. The peasant protests spread to Barcelona. On 7 June 1640, an uprising in Barcelona, known as the Corpus de Sang, killed several royal officials. The viceroy of Catalonia was assassinated. Mutinies continued. A few weeks later, Pau Claris, president of the Generalitat, formed a special assembly. This assembly took control and made revolutionary changes. They set up councils for justice, defense, and treasury. They also contacted France. After Tortosa fell to the royal army, the break with Spain became clear, and fighting began.

With the royal armies nearing Barcelona, on 17 January 1641, the assembly declared a Catalan Republic under France's protection. A week later, Catalonia accepted King Louis XIII of France as Count of Barcelona for more French military help. This allowed the French army to enter Spain. They defeated the Spanish army at the Battle of Montjuïc on 26 January 1641. The French general was made viceroy of Catalonia. But French control increased, and similar conflicts between peasants and French soldiers began.

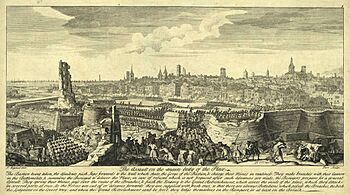

After many losses, Spanish forces drove out the French by 1644. By 1652, Barcelona fell after a year-long siege. Most of Catalonia was back under Spanish control. Philip IV recognized most of Catalonia's rights to end the conflict. When the war between Spain and France ended in 1659, the peace treaty gave the northern Catalan territories, Roussillon and northern Cerdanya, to France. Catalan institutions were removed in French Roussillon. In 1700, public use of the Catalan language was forbidden there.

The War of the Spanish Succession

In the late 17th century, during the reign of Spain's last Habsburg king, Charles II, Catalonia's population grew to about 500,000. The economy improved, especially along the coast. This growth was helped by exporting wine to England and the Netherlands. These countries couldn't trade with France due to trade wars. Many Catalans started to see England and the Netherlands as good examples for Catalonia.

However, Charles II died childless in 1700. The Crown of Spain went to his chosen successor, Philip V of the House of Bourbon. A group of countries, including Austria, England, and the Netherlands, supported a different claimant, Archduke Charles. This led to the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14). Catalonia first accepted Philip V. After talks, Philip V agreed that Catalonia would keep its old rights. Barcelona became a free port and could trade with America. But this didn't last. The viceroy's harsh rule and the king's authoritarian decisions, which went against Catalan laws, made Catalonia switch sides. In 1705, Archduke Charles entered Barcelona and was recognized as king.

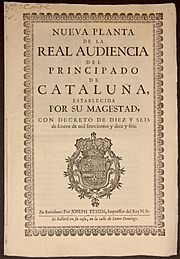

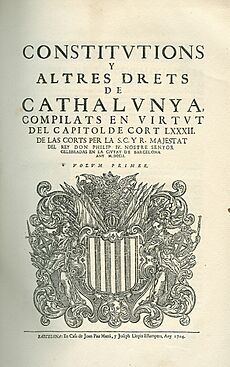

After much fighting, European changes led to peace with the Treaty of Utrecht (1713). This ended Catalonia's chance to resist Bourbon rule. Even though the Allied armies left, in July 1713, Catalonia decided to keep fighting. They wanted to protect Catalan rights and avoid punishment from the Bourbons. They raised the Army of Catalonia and sought help from Britain and Austria. After a 13-month siege by Spanish and French armies, Barcelona surrendered on 11 September 1714. King Philip V punished the Crown of Aragon. He issued the Nueva Planta decrees (1707 for Aragon and Valencia, 1716 for Catalonia). These laws abolished Catalan institutions and rights, except for civil law. They replaced them with Castilian ones, making the government an absolute monarchy. This ended Catalonia's status as a separate political entity. To ensure this, he created a new Royal Audience as the government seat. He replaced traditional Catalan divisions with Castilian ones. This was the first step in creating a unified Spanish nation.

Philip V closed the six Catalan universities. He founded a new one in Cervera. He also banned the use of the Catalan language in government. He secretly told royal officers to slowly introduce Castilian Spanish. Half a century later, under Charles III, Catalan was also banned from primary and secondary schools.

Catalonia in the 18th Century

Despite the harsh situation, Catalonia's economy grew again in the 18th century. It became a leader in early industrialization. The population and economy grew. Farming increased, and trade expanded. In the late 18th century, trade with America opened up. These changes helped set the stage for industrialization. The first signs appeared in cotton and textile manufacturing. By the end of the 18th century, working-class people started to feel the effects of becoming factory workers.

In the 1790s, new conflicts arose on the French border. This was due to the French Revolution. In 1793, after the French king was executed, Spain joined Britain against France. France then declared war on Spain. The War of the Pyrenees (Guerra Gran) had two main fronts. At first, the Spanish army entered Roussillon. But the French army pushed them back and entered Catalonia. The Sant Ferran Castle in Figueres fell to the French. In 1795, France and Spain signed the Peace of Basel, which restored peace.

Modern Period: Wars, Industry, and Identity (1808–1939)

Napoleonic Wars in Catalonia

In 1808, during the Napoleonic Wars, French troops occupied Catalonia. The official Spanish army disappeared. But people in Catalonia, like in other parts of Spain, resisted the French. This led to the Peninsular War. A local army defeated the French in battles at El Bruc, near Barcelona. Meanwhile, Girona was besieged by the French. Its people defended it bravely under General Mariano Álvarez de Castro. The French finally took the city on 10 December 1809. Many people died from hunger and disease. Álvarez de Castro died in prison a month later.

Resistance to French rule was organized through "juntas" (councils) across Spain. These councils stayed loyal to the Spanish royal family. In Catalonia, the local juntas formed the Superior Junta of the Government of the Principality of Catalonia. This group took over the powers of the old Royal Audience. At the same time, Napoleon took direct control of Catalonia. He created the Government of Catalonia and made Catalan an official language again for a short time. Between 1812 and 1813, Catalonia was directly joined to France. It was organized into four (later two) French departments. French rule in parts of Catalonia lasted until 1814. Then, the British General Wellington signed an agreement. The French left Barcelona and other strongholds.

Carlist Wars and a Changing Spain

The reign of Ferdinand VII (1808–33) saw several uprisings in Catalonia. After his death, a conflict over who would be king began. The "Carlist" supporters of Infante Carlos wanted an absolute monarchy. The liberal supporters of Isabella II wanted a more open government. This led to the First Carlist War (1833–1840), which was very intense in Catalonia. Catalonia was divided. Industrialized areas supported liberalism. The Catalan middle class tried to help build the new liberal state. Many Catalans fought for the Carlists. They hoped that bringing back the old system would also bring back their local rights and self-rule.

The liberals' victory led to a "middle-class revolution" during Isabella II's reign. In 1834, Spain was divided into provinces. Catalonia was split into four provinces: Barcelona, Girona, Lleida, and Tarragona. They did not have a common administration. Isabella II's reign was marked by corruption, inefficiency, and central control. Liberals soon split into "moderates" and "progressives." In Catalonia, a republican movement began. Catalans generally wanted a more federal Spain. In the middle of the century, there were several progressive uprisings in Barcelona, known as bullangues. The last uprising, the Jamància (1843), tried to remove General Espartero's government. It ended with Barcelona being bombed by the army. This showed the triumph of central control.

The Second Carlist War (1846–1849) mainly took place in Catalonia. Many people were unhappy with the liberal state. This explains why progressives and republicans worked with the Carlists in 1848. This happened at the same time as democratic revolutions in France and Europe.

When General O'Donnell became Prime Minister in 1856, relations between Catalonia and the Spanish government seemed to improve. Catalonia was enthusiastic about the Hispano-Moroccan War. A company of Catalan volunteers was formed. But the Liberal Union government fell before it could make expected reforms. The return of the moderates ended Catalan hopes.

In September 1868, Spain's economic crisis led to the September Revolution. Isabella II was removed from power. This began the "six democratic years" (1868–1874). As usual, popular revolts and juntas formed. General Joan Prim became Prime Minister. His government called for elections by universal manhood suffrage for the first time. In Catalonia, federalist republicans won most seats. Spain was declared a democratic monarchy, and Amadeo of Savoy was elected king. A few days before Amadeo arrived, Prim was assassinated. Meanwhile, federalist republicans in Catalonia, Aragon, Valencia, and the Balearic Islands signed the Tortosa Pact in 1869. There was also a federalist revolt that year.

Amadeo I's reign (1870–1873) was unstable. It saw the Third Carlist War, Cuba's fight for independence, and economic problems. The king resigned. This led to the First Spanish Republic (1873–1874). The Republic faced many problems. It had four presidents. Its first presidents, Estanislau Figueras and Francesc Pi i Margall, were Catalans. During this time, some radical federalists tried to declare a federated Catalan State. After President Emilio Castelar fell, General Pavia took power. He closed the parliament and appointed General Serrano as president without parliamentary control.

Industry, Culture, and Modern Art

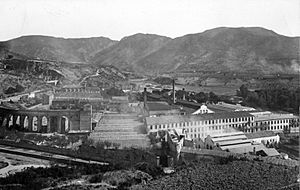

Since the 1830s, Catalonia became a center of Spain's industrialization. It became one of the largest textile producers in the Mediterranean. In 1832, the Bonaplata Factory was built. It was the first factory in Spain to use a steam engine. Catalonia had little energy resources and a weak Spanish market. To help industry grow, Spain used policies that reduced foreign competition. Catalonia saw the first railway in Spain in 1848, linking Barcelona with Mataró. These efforts helped industrial regions like Catalonia. Working-class people often lived and worked in very difficult conditions.

Because of the lack of energy, many factories were built near rivers. They used water turbines. These factories often included a company town (colònies industrials). Catalonia has many such towns, especially along the Ter and Llobregat rivers. These were small towns built around a factory in rural areas. They housed hundreds of people. These industrial colonies were a key part of Catalonia's industrialization. They were built from the second half of the 19th century. There are over 75 textile colonies recorded.

The mid-19th century saw a Catalan cultural rebirth, called the Renaixença. This movement aimed to bring back the Catalan language and culture. Like other Romantic movements, it admired the Middle Ages. In Barcelona, the literary contest called Floral Games (Jocs Florals) was brought back. Josep Pau Ballot wrote a grammar book for Catalan between 1810 and 1813. This work aimed to promote Catalan. Between 1833 and 1859, many writers used Catalan for literature but Spanish for their main works. However, common people continued to use Catalan. Popular theater in Catalan became important.

Catalan Identity and Worker Movements

In 1874, General Martínez Campos restored the Bourbon family to power. Alfonso XII became king. This period brought political stability. But it also saw the suppression of worker movements. Catalan nationalist identity slowly grew. In the early 20th century, political opposition grew again. This included republicanism, Catalan nationalism, and class-based politics.

The following decades saw the rise of political Catalanism. Valentí Almirall, a federalist republican, was a key figure. He tried to unite Catalan left and right-wing groups, but failed. He promoted the First Catalanist Congress in 1880. This congress aimed to unite different Catalanist groups. It agreed to create a Catalanist organization and work to make Catalan an official language. However, disagreements led to the group's breakup.

Conservative Catalan nationalists founded the League of Catalonia in 1887. In 1891, they joined with the La Renaixença group to form the Unió Catalanista (Catalanist Union). In 1892, the Unió wrote the Bases de Manresa. This program asked for special self-rule for Catalonia. In 1901, Enric Prat de la Riba and Francesc Cambó formed the Regionalist League. In 1906, they led the successful Solidaritat Catalana election group. This group was formed by various Catalan political parties. It was a response to the Cu-Cut! affair. Spanish Army officers attacked the Cu-Cut! magazine for a joke. The "Law of Jurisdictions" then put crimes against the army under military trials.

Catalan nationalism, led by Prat de la Riba, achieved partial self-government in 1913. This was for the "Commonwealth" (Mancomunitat). It was a grouping of the four Catalan provinces. Prat de la Riba was its first president. The Commonwealth built modern infrastructure like roads and telephones. It also promoted culture, education, and the Catalan language. In 1919, the Commonwealth proposed the first Statute of Autonomy. But disagreements with Madrid and opposition from parts of Spanish society led to its failure. The dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera suppressed the Commonwealth in 1925.

The Catalan worker movement in the early 20th century had three main groups: trade unionism, socialism, and anarchism. Barcelona was a center of worker protests. There were many strikes, assassinations, and the rise of the pro-anarchist Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT, founded in 1910). Growing anger over conscription led to the Tragic Week in Barcelona in 1909. Over 100 citizens died. Anarchists were active throughout the early 20th century. After a successful strike in 1919, they achieved the first eight-hour workday in Western Europe. Rising violence between Catalan workers and the middle class led the latter to support Primo de Rivera's dictatorship.

The initial acceptance of the Dictatorship by the conservative League made Catalan nationalism more leftist. Some groups, like Estat Català, became pro-independence. Primo de Rivera abolished the Commonwealth of Catalonia in 1925. He also repressed Catalan nationalism, the Catalan language, and worker movements. In 1926, Estat Català tried to free Catalonia with a small army. They wanted to declare an independent Catalan Republic. But the plan was discovered by French police. This made Francesc Macià and the Catalan cause famous worldwide.

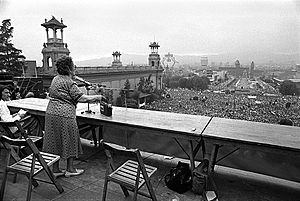

During the last years of the Dictatorship, Barcelona hosted the 1929 International Exposition. Spain also began to suffer an economic crisis.

Republic and Self-Government

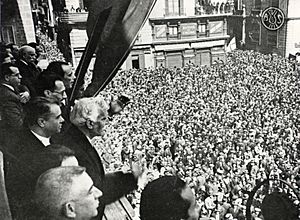

After Primo de Rivera's fall, the Catalan left worked to create a united front. This was led by Francesc Macià, founder of Estat Català. The Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (Republican Left of Catalonia, ERC) was a new party. It supported moderate socialism, republicanism, and Catalan self-determination. The party won a big victory in the local elections of 12 April 1931. This led to the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic on 14 April. After a short declaration of the Catalan Republic (14–17 April) by Macià, the Generalitat of Catalonia was brought back as a self-governing body. A Statute of Autonomy for Catalonia was approved on 9 September 1932. It gave Catalonia strong self-government and made Catalan an official language alongside Spanish. The Parliament of Catalonia was elected on 20 November 1932. The ERC won a large majority.

Under its two presidents, Francesc Macià (1931–1933) and Lluís Companys (1934–1939), the Generalitat did a lot of work. They improved culture, health, education, and civil law. This was despite a serious economic crisis. Macià died on 25 December 1933, and Companys became president. The Parliament continued to make laws to improve life for ordinary people. They approved laws like the Crop Contracts Law, which helped tenant farmers. This law caused a legal dispute with the Spanish government. Meanwhile, the Generalitat set up its own court and took over public order. The Statute was suspended in 1934 due to an uprising in Barcelona. President Companys declared the Catalan State of the Spanish Federal Republic. This was a response to a right-wing Spanish nationalist party joining the government. They feared this party was too close to fascism. The uprising was quickly put down by the Spanish army. Catalan government members were arrested.

The CNT, the largest trade union, faced problems. Some members were hostile to the Republic. Marxist parties united to form the POUM in 1935 and the PSUC in 1936.

After the left won the Spanish general election in February 1936, the Generalitat government was pardoned and returned to power. The period before the military rebellion in July 1936 was relatively peaceful in Catalonia. The Parliament resumed its work. The government prepared the People's Olympiad in Barcelona as a protest against the 1936 Berlin Olympics. But on the day it was supposed to start (19 July), the Spanish Army launched a coup. This led to the Spanish Civil War.

The Spanish Civil War in Catalonia

The military rebellion against the Republican government in Barcelona failed. This put Catalonia firmly on the Republican side. The victory of loyalist forces allowed worker militias, mainly anarchists, to gain real power. This led to harsh actions against those seen as "fascist" or right-wing. Both the Generalitat and the central government struggled to stop this violence. During the war, two powers existed in Catalonia: the official Generalitat and the powerful armed worker militias. To regain control, Companys allowed the creation of the Central Committee of Antifascist Militias of Catalonia (CCMA). This became the effective Catalan government for two months. It was replaced by a new Generalitat government that included anarchist ministers. Many parts of the economy came under the control of the CNT and UGT unions. Workers managed industries, services, and thousands of homes. The Generalitat approved a decree on "Collectivization and Workers' Control" in October 1936. This meant large companies were to be collectivized.

Violent clashes between worker parties happened in the 1937 May Days. The CNT-FAI and POUM were defeated. The PSUC then took strong action against them. The Generalitat slowly regained control, but it lost some of its self-rule within Republican Spain.

The Generalitat's military forces were on two fronts: Aragon and Majorca. The Majorca effort was a disaster. The Aragon front held firm until 1938. Then, Franco's troops broke the Republican territory in two. They occupied Vinaròs, cutting off Catalonia. The defeat of the Republican army in the Battle of the Ebro led to the occupation of Catalonia by Franco's forces in 1938 and 1939. Franco abolished Catalan self-government and brought in a dictatorship. He took strong measures against Catalan identity and culture. Only after Franco's death in 1975 and the adoption of a democratic constitution in 1978 did Catalonia regain its self-rule. The Generalitat was restored in 1977.

George Orwell served with the POUM in Catalonia from December 1936 to June 1937. His book, Homage to Catalonia, published in 1938, described his experiences. It is one of the most widely read books about the Spanish Civil War.

Contemporary Period: From Dictatorship to Democracy (1939–Present)

Franco's Rule and Its End

Like the rest of Spain, Catalonia under Franco (1939–1975) saw the end of democratic freedoms. Political parties were banned, censorship was strict, and leftist groups were forbidden. In Catalonia, this also meant the end of the Statute of Autonomy. All specific Catalan institutions and laws were abolished. Catalan was suppressed and only used within families. Spanish became the only language for education, government, and media. In the early years, any resistance was stopped. Prisons filled with political prisoners. Thousands of Catalans went into exile. About 4,000 Catalans were executed, including former Generalitat president Lluís Companys.

The Civil War had badly damaged Spain's economy. Recovery was very slow. Catalonia's economy didn't reach pre-war levels until the late 1950s. After a period of self-sufficiency, Franco's government changed its economic policies in 1959. In the 1960s and early 1970s, the economy grew rapidly. This was known as the Spanish Miracle. International companies built factories in Spain. Salaries were low, strikes were forbidden, and regulations were few. Catalonia prospered as industry expanded. Workers migrated from rural areas across Spain to Barcelona. This made Barcelona one of Europe's largest industrial areas. Working-class opposition to Franco began to appear secretly. The Comisiones Obreras (Workers Commissions) union revived, as did the PSUC. Student protests became frequent. In the 1970s, democratic groups united under the Assembly of Catalonia. They demanded freedom, amnesty for political prisoners, and the return of Catalonia's self-rule.

Later in Franco's rule, some Catalan folk and religious celebrations were allowed. Catalan language in mass media was forbidden, but allowed in theater from the early 1950s. In the 1960s and 70s, Catalan music saw a revival known as Nova Cançó. It started with the Els Setze Jutges group. It became a popular movement that included protest songs against the dictatorship. It helped launch famous singers like Joan Manuel Serrat and Lluís Llach.

Democracy Returns to Catalonia

Franco's death began the "democratic transition." Democratic freedoms were restored, leading to the Spanish Constitution of 1978. This constitution recognized different national communities within Spain. It proposed dividing the country into autonomous communities. After the first general election in 1977, the Generalitat was restored as a temporary government. It was led by its president in exile, Josep Tarradellas. In 1979, the new Statute of Autonomy was approved. It gave Catalonia more self-rule in education and culture than the 1932 Statute. But it gave less power over justice and public order. Catalonia was defined as a "nationality." Catalan was recognized as Catalonia's own language and became co-official with Spanish. The first election to the Parliament of Catalonia under this Statute made Jordi Pujol president. He held this position until 2003.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Catalonia's self-governing institutions grew. These included an autonomous police force, the Mossos d'Esquadra. Local administrations called comarcal were restored. A High Court was also established. Catalonia's Law of Linguistic Normalization promoted Catalan-language media. The TV network Televisió de Catalunya and its first channel TV3, which broadcast mainly in Catalan, were created in 1983. The Catalan government also supported Catalan culture.

In 1992, Barcelona hosted the Summer Olympics. This brought international attention to Catalonia. In the 1990s, no single party had a majority in the Spanish parliament. Governments relied on support from nationalist parties, including Catalan ones. This helped Catalonia gain more self-rule.

In November 2003, elections for the Generalitat resulted in a left-wing nationalist coalition. Pasqual Maragall became the new president. This government was unstable, especially over reforming the Statute of Autonomy. The Statute was approved by the Catalan Parliament in 2005. It was then sent to the Spanish parliament and approved in 2006. Catalan citizens ratified it on 18 June 2006. The new Statute strengthened self-government. It also included the definition of Catalonia as a nation. Internal tensions led to new elections in 2006. A coalition again formed, with José Montilla as president.

On 16 September 2005, the ICANN approved the domain.cat. This was the first internet domain for a language community.

The Independence Movement

The new Statute of Autonomy was challenged by some Spanish nationalist groups. The conservative People's Party sent the law to the Constitutional Court of Spain. In 2010, the court declared some articles invalid. These articles dealt with Catalonia's justice system, funding, the status of the Catalan language, and references to Catalonia as a nation. In response, a large demonstration was held on 10 July 2010. People started organizing to demand the right to decide their future. The economic crisis deeply affected Spain. The CiU won the Catalan election of 2010. Its leader, Artur Mas, became president. His government carried out austerity measures. On Catalonia's National Day, 11 September 2012, a huge demonstration in Barcelona called for independence and a referendum.

On 23 January 2013, the Catalan parliament approved a Catalan Sovereignty Declaration. It stated that Catalonia is a sovereign entity and called for an independence referendum. Spanish institutions tried to stop it. On 9 November 2014, the Government of Catalonia organized an independence referendum. About 1.6 million out of 5.4 million possible voters supported independence. On 9 November 2015, the parliament approved a declaration to start the process of creating an independent Catalan republic.

The 2017 Independence Referendum

Quick facts for kids

Catalan Republic

República Catalana

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Anthem: Els Segadors (The Reapers)

|

|||||||||

Location of the Catalan Republic within Europe.

|

|||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized state | ||||||||

| Largest city | Barcelona | ||||||||

| Official languages | Catalan, Occitan, Spanish | ||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

|

• President

|

Carles Puigdemont | ||||||||

|

• Vice President

|

Oriol Junqueras | ||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||

| Unrecognised State | |||||||||

| 1 October 2017 | |||||||||

| 27 October 2017 | |||||||||

|

• Independence suspended

|

27 October 2017 | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

|

• 2016 census

|

7.523 million | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

A controversial and illegal independence referendum was held in Catalonia on 1 October 2017. It used a disputed voting process. The Constitutional Court of Spain declared it illegal on 6 September 2017. The European Commission also agreed it was illegal. The referendum asked: "Do you want Catalonia to become an independent state in the form of a republic?" More than 2,020,000 voters (91.96%) said "Yes." About 177,000 said "No." The turnout was 43.03%. The Catalan government said that up to 770,000 votes were not cast because polling stations were closed by police. They also said that police actions caused injuries to about 1,000 people. Many voters who did not support independence did not vote.

Catalonia declared independence. The independence motion passed in the Catalan assembly on 27 October 2017. There were 70 votes in favor, 10 against, and two blank ballots. Hours later, the Spanish Senate used Article 155 of the Spanish Constitution. This allowed Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy's government to take direct control of Catalonia. Rajoy dissolved the Catalan Parliament and dismissed Catalonia's Government, including its president, Carles Puigdemont. Rajoy called for a new Catalan parliamentary election on 21 December 2017.

Spanish Deputy Prime Minister Soraya Saenz de Santamaria took over the functions of the President of Catalonia. She gained full control over the Catalan administration. Josep Lluís Trapero was removed as chief of the Catalan police.

On 1 May 2018, Quim Torra was elected President of Catalonia. This happened after Spanish courts blocked the election of Carles Puigdemont and other candidates. Carles Puigdemont was declared ineligible after leaving Spain.

On 1 June 2018, a vote of no confidence in the Spanish government was successful. This led to the downfall of Mariano Rajoy. Socialist leader Pedro Sánchez became the new Prime Minister of Spain. Catalan nationalist parties played a key role in Rajoy's removal.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Cataluña para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Cataluña para niños

- Timeline of Catalan history

- History of Andorra

- History of Barcelona

- Count of Barcelona

- List of presidents of the Government of Catalonia

- Military history of Catalonia

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |