Fred Allen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Fred Allen

|

|

|---|---|

Fred Allen circa 1940

|

|

| Born |

John Florence Sullivan

May 31, 1894 Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Died | March 17, 1956 (aged 61) Manhattan, New York, U.S.

|

| Spouse(s) |

Portland Hoffa

(m. 1927) |

| Career | |

| Show | The Fred Allen Show |

| Network | CBS, NBC |

| Style | Comedian |

| Country | United States |

John Florence Sullivan (born May 31, 1894 – died March 17, 1956), known as Fred Allen, was a famous American comedian. His radio show, The Fred Allen Show (1932–1949), was very popular. It made him one of the most important humorists during the Golden Age of American radio.

Fred Allen was known for his long-running pretend fight with his friend, fellow comedian Jack Benny. But he was popular for many other reasons too. A radio historian named John Dunning said Allen was perhaps radio's most admired comedian. He was also often censored (meaning parts of his show were not allowed to be broadcast). Allen was great at making up jokes on the spot. He often argued with the radio network bosses and even joked about these fights on the air. His style of comedy influenced many other comedians, like Groucho Marx and Johnny Carson. Even famous people like President Franklin D. Roosevelt and writers William Faulkner and John Steinbeck were his fans.

Fred Allen received stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for his work in television and radio.

Contents

Early Life and Childhood

John Florence Sullivan was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His parents were Irish Catholic. Fred Allen's mother, Cecilia Herlihy Sullivan, died when he was almost three years old. He and his baby brother Robert went to live with their aunt Lizzie. Allen's father later remarried. He gave his sons a choice: come with him or stay with Aunt Lizzie. Allen's younger brother went with their father, but Fred Allen chose to stay with his aunt. He later wrote that he never regretted this choice.

Vaudeville Career

As a boy, Allen took piano lessons. He learned only two songs! He also worked at the Boston Public Library. There, he found a book about how comedy began and grew. He also started learning to juggle.

Some co-workers at the library planned a show. They asked him to juggle and do some comedy. A girl in the audience told him he should become a performer. This made Allen decide what he wanted to do with his life.

In 1914, when he was 20, Allen started working in local vaudeville shows. He earned $30 a week, which was enough to quit his other jobs. He first used the stage name Fred St. James, then "Freddy James." He often called himself "the world's worst juggler." Allen mixed his clumsy juggling with jokes. He often made fun of his own bad juggling. During a ten-year world tour, his act changed. It became more about talking comedy and less about juggling. In 1917, he changed his stage name to Fred Allen. This was so theater owners would not pay him the low salary he got earlier in his career. His new last name came from Edgar Allen, a booker for theaters.

In 1922, Allen had a special theater curtain made. It was painted with a cemetery where old jokes went to "die." This was called the "Old Joke Cemetery." Audiences would laugh at the curtain before Allen even came on stage.

Allen used different tricks in his act, like a ventriloquist dummy or singing. But his comedy was always the main focus. He loved to play with words. One of his funny bits was reading a fake "letter from home." It would have silly news like: "The man next door has bought pigs; we got wind of it this morning."

Allen's humor was sometimes for other performers, not just the audience. Once, after a show didn't go well, he sent out a fake obituary (death notice) for his act. He also mailed small bottles of his "flop sweat" (sweat from a bad performance) to newspapers as a joke.

In 1921, Fred Allen toured with singer Nora Bayes. Their music director was a young Richard Rodgers, who later became a very famous composer. Rodgers remembered Allen's act, sitting on the stage edge, playing a banjo and telling jokes.

Broadway Shows

Fred Allen left vaudeville and started working in Shubert Brothers stage shows. One of these was The Passing Show in 1922. The show didn't last long on Broadway. But Allen met Portland Hoffa there. She was one of the chorus girls. They married in 1927 and stayed together until his death.

He also got good reviews for his comedy in other shows like Vogues. He kept improving his comedy writing. He even wrote a column for Variety magazine called "Near Fun." Allen wanted to write full-time, but a disagreement about money ended the column.

After he and Portland married, Allen started writing comedy for them to perform together. They traveled for shows and spent summers in Maine.

Radio Career

Fred Allen and Portland Hoffa first tried radio while waiting for a new musical. They appeared on a Chicago radio station's show called WLS Showboat. Allen said they were there "to inject a little class into it." Their radio success helped their theater shows. People in the Midwest liked to see their radio favorites in person.

They eventually got their musical, Polly. A young English actor named Archie Leach was also in the cast. He got good reviews for his charm, just as Allen did for his comedy. Archie Leach later moved to Hollywood and changed his name to Cary Grant.

Polly was not a big hit. But Allen went on to other successful shows like The Little Show (1929–30). This led to him working full-time in radio in 1932.

Town Hall Tonight

Allen first hosted The Linit Bath Club Revue on CBS. He then moved to NBC and the show changed names several times. It became The Salad Bowl Revue, then The Sal Hepatica Revue, and finally Town Hall Tonight (1935–39). In 1939–40, his sponsor, Bristol-Myers, changed the name to The Fred Allen Show. Allen didn't like this change. He was a perfectionist and often changed sponsors until Town Hall Tonight allowed him to create the small-town setting he wanted. This show made him a true radio star.

The hour-long show had parts that influenced later radio and TV shows. For example, his "The News Reel" segment, which made fun of the news, influenced shows like Saturday Night Live's "Weekend Update." The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson had "Mighty Carson Art Players," which was inspired by Allen's "Mighty Allen Art Players." Allen and his cast also made fun of popular musicals and movies.

Town Hall Tonight was the longest-running hour-long comedy show in classic radio history. In 1940, Allen moved back to CBS Radio with a new sponsor and show name, Texaco Star Theater. By 1942, the show was shortened to half an hour. Allen also didn't like being forced to have famous guests instead of the unknown, amateur guests he used to feature.

Back to NBC

Fred Allen took a year off because of high blood pressure. He returned in 1945 with The Fred Allen Show on NBC. It aired on Sunday nights.

Allen made some changes to the show. He added the singing DeMarco Sisters. Their cheerful singing of "Mr. Al-len, Mr. Alll-llennnn" became a famous part of the show's opening. During a short pause in the song, Allen would say something funny, like, "It isn't the mayor of Anaheim, Azusa and Cucamonga, kiddies."

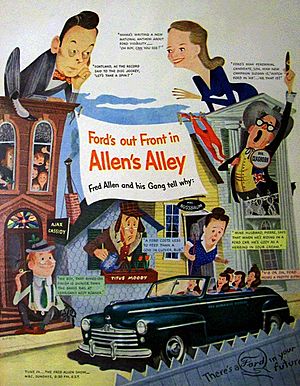

Allen's Alley

Another big change, which started in the Texaco days, was "Allen's Alley." This segment became his most famous. It was inspired by stories about small-town people written by a popular newspaper columnist, O. O. McIntyre.

"Allen's Alley" always followed a short monologue by Allen and a funny bit with Portland Hoffa. She would usually tell jokes about her family. Then, a short music break would play, showing them "walking" to the imaginary Alley.

The segment always began with Portland asking Allen what he would ask the people in the Alley that week. After she asked, "Shall we go?" Allen would reply with funny lines like, "As the two drumsticks said when they spotted the tympani, let's beat it!"

A group of funny, typical characters would greet Allen and Hoffa in the Alley. They would talk about Allen's question of the week. This question was usually about current news or popular events, like gas rationing or the circus coming to town.

Allen had writers, but he did most of the final editing and rewriting of each week's script. He would work up to twelve hours a day on ideas and jokes. He was so good at making up jokes on the spot that his show often ran late. He would often sign off by saying, "We're a little late, so good night, folks."

Allen's habit of running late affected the show that followed his, Take It or Leave It, hosted by Phil Baker. Baker once kept track of how much time he lost to Allen. When it reached 15 minutes, Baker walked into Allen's studio 15 minutes early and took over the show! Allen was surprised but amused.

Allen also had a funny way of dealing with jokes that didn't land well. If a joke was met with silence, he would comment on the lack of laughter. His made-up "explanation" was almost always funnier than the original joke. Johnny Carson later used this technique successfully.

Ending the Alley

The Fred Allen Show was the top-rated radio show in the 1946–47 season. Allen got a great new contract because his show was so successful. NBC also wanted to keep its stars from moving to CBS, like Jack Benny did.

But a year later, his ratings dropped. A new quiz show called Stop the Music on ABC became very popular. This show asked listeners to call in live by telephone. Allen tried to fight back. He offered $5,000 to anyone who got a call from Stop the Music while listening to his show. He never had to pay anyone. He also made fun of game shows on his program.

Unfortunately, Allen's show fell to number 38 in the radio ratings. This was also because television was becoming popular in many cities. He changed the show again, moving "Allen's Alley" to "Main Street." He left radio in 1949, partly because his doctor told him to rest due to his high blood pressure. He took a year off, but he never hosted another full-time radio show again.

The Famous Feud

Fred Allen and Jack Benny were good friends in real life. But in 1937, they started a running joke that became very famous. A child violin player named Stuart Canin performed very well on Allen's show. Allen then joked about "a certain alleged violinist" (meaning Benny) who should be ashamed of his bad playing. Allen knew Benny would be listening. Benny laughed and joked back on his own show. This pretend rivalry went on for ten years! Some fans actually believed the two comedians were real enemies.

The Allen-Benny feud was the longest and most remembered running joke in classic radio history. The joke even led to a planned boxing match between them, which sold out, but never happened. The two comedians also appeared together in movies. These included Love Thy Neighbor (1940) and It's in the Bag! (1945). It's in the Bag! was Allen's only starring movie.

See also

In Spanish: Fred Allen para niños

In Spanish: Fred Allen para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |