French war planning 1920–1940 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Dyle-Breda Plan/Breda variant |

|

|---|---|

| Part of The Second World War | |

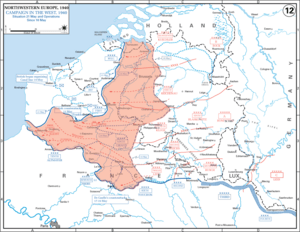

Western Front campaign, 1940

|

|

| Operational scope | Strategic |

| Location | South-west Netherlands, central Belgium, northern France 50°51′00″N 04°21′00″E / 50.85000°N 4.35000°E |

| Planned | 1940 |

| Planned by | Maurice Gamelin |

| Commanded by | Alphonse Georges |

| Objective | Defence of the Netherlands, Belgium and France |

| Date | 10 May 1940 |

| Executed by | French 1st Army Group British Expeditionary Force Belgian Army |

| Outcome | Defeat |

The Dyle Plan (also known as Plan D) was a military strategy created by Maurice Gamelin, the Commander-in-Chief of the French Army. Its main goal was to stop a German invasion of France that was expected to come through Belgium. The plan involved French, British, and Belgian troops setting up a strong defense line along the Dyle River in Belgium. This river is about 86 kilometers (53 miles) long.

Before this, France and Belgium had a military agreement from 1920 to work together on defenses. However, after Germany re-militarized the Rhineland in 1936 (meaning they put troops back in an area near the Belgian border that was supposed to be demilitarized), Belgium decided to become strictly neutral. This meant they wouldn't openly cooperate with France anymore.

French military leaders worried if their troops could move fast enough into Belgium to get into defensive positions before the Germans arrived. They considered two main plans for defending forward in Belgium: the Escaut Plan (Plan E) and the Dyle Plan (Plan D). Gamelin first preferred the Escaut Plan, but then chose the Dyle Plan because its defensive line was 70–80 kilometers (43–50 miles) shorter. Some officers at the French Army Headquarters (GQG) doubted if they could reach the Dyle River before the Germans.

During the winter of 1939–1940, Germany was also changing its invasion plan, known as Fall Gelb (Case Yellow). On January 10, 1940, a German aircraft carrying invasion plans accidentally landed in Belgium. This event, called the Mechelen Incident, made the Germans rethink their plan. It led to the Manstein Plan, a risky idea to attack further south through the Ardennes forest. The attack on Belgium and the Netherlands would then become a trick to draw Allied armies north, making it easier to surround them from the south.

Gamelin also updated the Dyle Plan with the Breda variant. This involved the French Seventh Army, a very strong and mobile force, advancing into the Netherlands to the city of Breda. The idea was for them to connect with the Dutch Army and protect the Scheldt Estuary. This meant some of France's best divisions were moved north, while Germany was secretly moving its elite units south for the new Ardennes attack.

Why France Prepared for War

Protecting French Borders

After World War I, France regained important areas like Alsace and Lorraine. These regions had valuable natural resources, industries, and many people, which were crucial for any future war. French military leaders knew they couldn't afford to retreat deep into France as they had in 1914. So, protecting these border areas became very important.

The French Army decided that if war came again, they needed to defend their northern border by quickly moving into Belgium. They believed that losing important resources in northern France could not happen again.

The Maginot Line

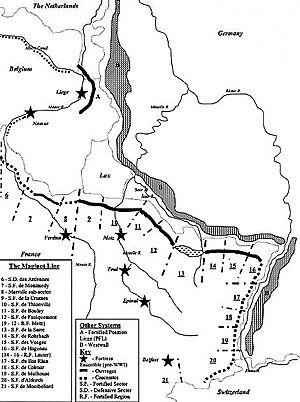

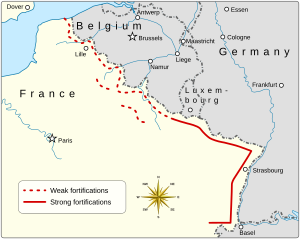

To protect their eastern border with Germany, France built a huge line of fortifications called the Maginot Line. This was a series of strong forts, underground tunnels, and gun positions. It was designed to protect key areas like the Moselle Valley and the industrial regions of Lorraine.

The Maginot Line was meant to stop a German invasion for about three weeks. This would give the French army enough time to get all its soldiers ready for battle. The forts were built with thick concrete walls and armed with machine guns and anti-tank weapons. They also had obstacles like barbed wire and anti-tank barriers.

The Ardennes Forest

The Ardennes forest, which stretches across parts of Belgium, Luxembourg, and France, was considered a very difficult place for an army to attack through. It had narrow, winding roads, thick woods, and hills. French military experts believed that these natural obstacles could easily be blocked with fallen trees, mines, and roadblocks.

They thought that any large army trying to pass through the Ardennes would be slowed down a lot. Also, the Meuse River beyond the Ardennes was another big obstacle. French leaders believed they would have plenty of time to send reinforcements to the area if an attack came from there.

The Northern Border with Belgium

The border between France and Belgium, from Luxembourg to Dunkirk, was seen as the hardest to defend. Unlike the hilly areas of the Maginot Line, this region was flat and open. This meant it would need much more extensive fortifications, and the high water table made it difficult to dig deep defenses.

Also, a large industrial area with cities like Lille was right on the border. This made it hard to build a prepared battlefield with trenches and tank traps. There were also many roads and railways leading straight to Paris. French leaders thought that fortifying this border too much might make Belgium suspicious. They believed that Belgium was the most likely route for a German invasion, just like in 1914.

Planning for the Invasion

The Escaut Plan and Dyle Plan

When France declared war on Germany in September 1939, their military strategy was clear: defend on the right (east) and advance into Belgium on the left (north). The goal was to fight the Germans away from French soil.

Because Belgium had declared neutrality, they were hesitant to openly work with France. However, they did share some information about their defenses. French forces gathered along the Belgian border, ready to move quickly and set up defenses before the Germans arrived.

General Gamelin, the French Commander-in-chief, initially preferred the Escaut Plan (Plan E). This plan involved defending along the Escaut (Scheldt) River. But he later chose the Dyle Plan (Plan D), which involved defending a shorter line along the Dyle River. He believed this line could be reached faster.

Allied Intelligence and Warnings

By October 1939, Germany had prepared its invasion plan, Fall Gelb (Case Yellow), which aimed to attack through Belgium. The goal was to defeat the Allies, occupy parts of the Netherlands, Belgium, and northern France, and protect Germany's industrial heartland.

Allies received several warnings about the German offensive through spies and secret intelligence (Ultra). For example, a warning came in November 1939 that the attack would begin on November 12. However, these attacks were often postponed by Hitler. French and British intelligence were sure that Germany could launch an invasion quickly, leaving little time to react.

The Mechelen Incident

On January 10, 1940, a German plane made an emergency landing in Belgium. On board was an officer carrying secret German air force plans for an attack through central Belgium. Belgian authorities seized the documents and shared them with Allied intelligence. At first, the Allies thought it might be a trick.

However, the Germans believed their plans were now known. So, on February 24, they secretly changed their main attack plan. They moved twenty divisions, including many tank divisions, from the Belgian border to the Ardennes area. French intelligence noticed some troop movements but didn't realize the main German attack would now come through the Ardennes.

The Dyle Plan in 1940

By late 1939, Belgium had improved its defenses along the Albert Canal. Gamelin and the French Headquarters (GQG) decided that defending along the Dyle Line was possible. The British also agreed to this plan.

The Dyle Plan involved the French First Army Group defending France from the English Channel to the Maginot Line. The French Seventh Army would move into the Netherlands, while the Belgians would try to slow down the Germans at the Albert Canal before retreating to the Dyle River. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) would defend a section of the Dyle, and the French First Army would hold the area from Wavre to Namur, including the important Gembloux Gap.

The French Ninth Army would be positioned south of Namur along the Meuse River, next to the Second Army, which held the right flank of the First Army Group. French commanders thought these armies had an easier job because they were dug in on easily defended ground behind the Ardennes.

The Breda Variant

The Breda variant was an addition to the Dyle Plan. It aimed to control the Scheldt Estuary so supplies could reach Antwerp by ship and connect with the Dutch army. Gamelin decided that the French Seventh Army, with its strong and mobile divisions, would advance all the way to Breda in the Netherlands to link up with the Dutch. This was a long advance of about 175 kilometers (109 miles), while German armies were only 90 kilometers (56 miles) from Breda.

The Battle Begins (May 1940)

First Army Group in Action

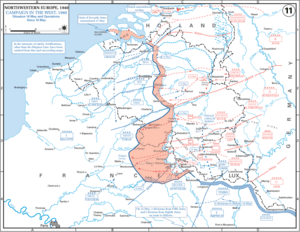

Early on May 10, 1940, the German invasion began. German bombers attacked targets in the Netherlands, and paratroopers landed on airfields. The French Seventh Army quickly moved forward on the northern flank, reaching Breda by May 11. However, the Germans had already captured key areas in the Netherlands and cut off the Dutch army.

The French Seventh Army faced strong German resistance, including tanks and dive-bombers. The Breda variant plan failed in less than two days. On May 12, Gamelin ordered the Seventh Army to stop its advance and retreat to cover Antwerp. By May 14, much of the Netherlands was overrun, and the Dutch government surrendered the next day.

In Belgium, German attacks began on the Albert Canal defense line, including the strong Fort Eben-Emael. German paratroopers and glider troops quickly captured the fort, forcing the Belgian Army to retreat to the Dyle Line on May 12. This was too soon for the French First Army to fully set up its defenses.

French cavalry units reached the Gembloux Gap and found it was not as fortified as expected. There were few anti-tank defenses or trenches. French officers were worried, but the plan continued. The French cavalry fought a delaying action against German tanks in the Battle of Hannut (May 12–14). French tanks, like the Somua S35s, performed well against German tanks. The cavalry then pulled back behind the French First Army, which had arrived at the Dyle Line.

On May 15, the Germans attacked the First Army along the Dyle, leading to the Battle of Gembloux. The French First Army successfully pushed back the German tank corps. However, French headquarters soon realized that the main German attack was happening much further south, through the Ardennes.

The First Army began to retreat towards Charleroi, and the British also started to pull back. By May 18, Allied forces in Belgium were retreating towards the Escaut River and the French border. The Germans, meanwhile, focused their main effort on advancing from the Meuse River towards the English Channel coast. By May 20, they reached Abbeville, cutting off the Allied armies in the north.

The Ardennes Attack

While the Allies were focused on Belgium, German tank divisions secretly advanced through the Ardennes forest. They aimed for the Meuse River, surprising the French Second and Ninth armies. The French cavalry divisions in the area were quickly pushed back.

French commanders initially thought these German units were just small advance parties and would wait before crossing the Meuse. However, on May 13, the German air force launched a massive bombing attack on French defenses around Sedan, lasting eight hours with about 1,000 aircraft.

Although there wasn't much physical damage, the morale of the French troops collapsed. Panic spread, and German troops crossed the Meuse River that afternoon. Allied attempts to bomb the bridges were very costly failures, with many planes shot down.

French armored divisions sent to counter-attack were often caught off guard or delayed by refugees on the roads. For example, the French 1st Armored Division was caught while refueling and was largely destroyed by the German 7th Panzer Division.

The German advance through the Ardennes was swift and largely unopposed after the initial breakthrough. By May 16, the Germans had pushed deep into France, reaching areas like Laon. The First Army Group was ordered to retreat from the Dyle Line to avoid being trapped by this unexpected German breakthrough. The Germans continued their rapid advance, reaching the Channel coast by May 20, effectively cutting off the Allied armies in Belgium and northern France.

Aftermath of the Battle

The Battle of Hannut

The Battle of Hannut was the first major tank battle of the campaign. French light and medium tanks, like the Hotchkiss and Somua S35s, faced German Panzer III and Panzer IV tanks. The French tanks were often better in terms of firepower and armor. The French also had armored cars with powerful anti-tank guns.

The French tanks fought defensively, using villages for cover. Despite some communication issues, they managed to destroy or damage a significant number of German tanks. The German 4th Panzer Division lost about 45–50 percent of its tanks, and the 3rd Panzer Division lost 20–25 percent. Even though many damaged German tanks were quickly repaired, their fighting strength was reduced.

From a tactical point of view, the French victory at Hannut bought time for the First Army to set up defenses on the Dyle Line. However, at a larger strategic level, this French success was actually part of a German trick. The German attack in central Belgium was a decoy to draw Allied forces north. This meant the French victory at Hannut became less important in the overall campaign. The French tank units that fought so well at Hannut would have been much more useful for a counter-attack against the German breakthrough at Sedan in the Ardennes. But by then, they had suffered too many losses.

Images for kids

-

View of the Meuse in the French Ardennes

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |