George Washington Dixon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

George Washington Dixon

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 1801 Richmond, Virginia, U.S.

|

| Died | March 2, 1861 (aged 59–60) |

George Washington Dixon (born around 1801 – died March 2, 1861) was an American singer, stage actor, and newspaper editor. He became famous for his performances in "blackface," a type of entertainment where performers used makeup to look like Black people. He sang popular songs like "Coal Black Rose" and "Zip Coon".

Later, Dixon became a journalist. He often wrote articles that criticized wealthy people, which made him many enemies.

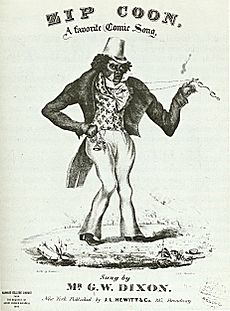

At age 15, Dixon joined the circus. He quickly became known for his singing. In 1829, he started performing "Coal Black Rose" in blackface. These types of songs made him a star. Unlike other performers of his time, Dixon was mostly a singer, not a dancer. People said he had a great voice, and many of his songs were very difficult to sing. "Zip Coon" became his most famous song.

By 1835, Dixon saw journalism as his main job. His first big newspaper was Dixon's Daily Review, which he published in Lowell, Massachusetts. In 1836, he started Dixon's Saturday Night Express in Boston. He used his newspapers to expose what he believed were wrongdoings by the upper classes. These stories caused him a lot of trouble. His most successful paper was the Polyanthos, which he started in 1838 in New York City. Through this paper, he challenged powerful people. After trying out other things like hypnotism and long-distance walking, he moved to New Orleans, Louisiana.

Contents

Early Life and Rise to Fame

We don't know much about Dixon's childhood. Records suggest he was born in Richmond, Virginia, likely in 1801. His family was working-class, and he might have gone to a charity school. Descriptions of Dixon say he had a dark complexion and "splendid head of hair." There were questions about whether he was white or Black, but most evidence suggests he was white with very distant Black ancestry.

A newspaper story from 1841 says that when Dixon was 15, a circus owner named West noticed his singing. Dixon joined the circus as a stablehand and errand boy. He traveled with circuses for a while and was listed as a singer and poet in shows as early as 1824. By 1829, he was known as "The American Buffo Singer."

In July 1829, Dixon performed "Coal Black Rose" in blackface at three theaters in New York City. His shows attracted mostly working-class audiences. These performances were a huge success, and Dixon became very famous. On December 14, a show featuring Dixon at the Albany Theatre made $155.87, which was a lot of money for that time.

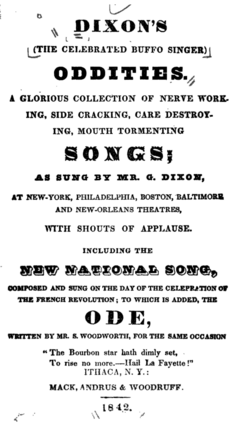

Dixon performed until 1834, mostly in New York's main theaters. Besides blackface songs and dances, he also performed whiteface songs and scenes from popular plays. Much of his material was quite challenging to perform. His fame allowed him to add humor and political comments to his acts. In November 1830, he sang for a huge crowd in Washington, D.C., to support the July Revolution in France. He started selling a book of his popular songs and skits called Dixon's Oddities in 1830, which stayed in print for a long time. Dixon mostly performed for working-class people. His songs included "The New York Fireman," which compared firefighters to the American Founding Fathers. He also gave speeches. In December 1832, a newspaper reported that Dixon would read a speech from the President at the Front Street Theatre.

In 1833, he started a small newspaper called the Stonington Cannon. However, it wasn't very successful. By January 1834, he was back to performing, now with new skills like ventriloquism. Reviews said his voice was "of remarkable richness and compass."

In March, Dixon performed "Zip Coon" for the first time. This song quickly became a favorite and Dixon's signature tune. He later claimed he wrote the song, but others performed it before him, so this is unlikely. Dixon often danced a lively jig while singing.

Dixon as a Newspaper Editor

In early 1835, Dixon moved to Lowell, Massachusetts, a growing town during the Industrial Revolution. By April, he was known as "The National Melodist" and was editing Dixon's Daily Review. The newspaper supported the Whig Party and working-class people. Dixon's Daily Review also discussed important topics like good behavior and women's roles in the changing cities of the North.

Dixon's criticism of others didn't make him popular. By July, he had sold his paper. By August, rumors said Dixon had started another paper called the News Letter.

By February 1836, Dixon was touring again. He played many popular shows in Boston and performed a play at the Tremont Theatre.

In April, Dixon performed at the Masonic Temple in Boston. He included songs that appealed to his working-class audience, like a popular tune with lyrics about the Boston Fire Department. However, he also tried to attract wealthier, middle-class people. For example, he performed with a classically trained pianist and called the show a "concert," a word usually used for high-class entertainment.

By the end of 1836, Dixon had moved to Boston and started a new paper, the Bostonian; or, Dixon's Saturday Night Express. This paper focused on working-class issues and religious values. It continued to expose the alleged immoral actions of well-known Bostonians. Other Boston papers called his stories false. Dixon responded by making fun of the editor of one of those papers.

In early 1837, Dixon faced more legal issues. A judge eventually dismissed the case. Dixon gave a speech to the public after the trial.

Dixon's trial in March 1837 ended with him being found guilty. He appealed, but the jury couldn't agree, and the charges were dropped. He gave another of his famous speeches after the trial. A newspaper wrote that Dixon seemed to have a "charmed life" and could "defy the majesty of the law."

Another stage tour followed, with concerts in Lowell, New England, and Maine. This tour was very successful. One reviewer said Dixon had "a voice which all unite in pronouncing to be of remarkable richness and compass." That fall, he performed at the upper-class Opera Saloon, singing songs from popular operas. His fame, or perhaps his reputation, even led to him being listed as a candidate for the Boston mayoral race in December. Dixon received nine votes, even though he politely said he wouldn't serve if elected.

The Polyanthos Newspaper

Dixon performed in Boston until February 1838. That spring, he moved to New York City. There, he started a new newspaper called the Polyanthos and Fire Department Album. Dixon again supported the lower class and aimed to expose the secrets of the rich, especially those who took advantage of working-class women.

Dixon faced legal challenges related to his articles. He spent time in jail while awaiting trials. After a jury couldn't agree on a verdict in one case, and other charges were dropped, Dixon was eventually released.

Dixon continued to defend himself and his reasons in the Polyanthos. He seemed to have some success, as one newspaper admitted that his trial had revealed some unpleasant things about the upper class. However, Dixon later pleaded guilty to some charges and was sentenced to six months of hard labor at the New York State Penitentiary. He reportedly said, "This is a pretty situation for an editor." He later claimed that someone had paid him to change his plea.

After serving his sentence, Dixon returned to New York. He restarted the Polyanthos. He became a leader among editors who wanted to expose bad behavior.

Dixon continued his work, even using drawings in his newspaper to criticize people. When a grand jury called a certain person a "public nuisance," Dixon responded with the headline "Restell caught at last!" This person was later arrested. Dixon claimed he was right and covered the trial in his newspaper. After the conviction, he wrote that "the monster in human shape... has... been convicted of one of the most hellish acts ever perpetrated in a Christian land!"

In September, a man attacked Dixon in the street. This led to some of the only positive newspaper coverage Dixon received that wasn't about his singing. One paper praised his editing and writing.

Even with positive press, Dixon's legal troubles continued. He was arrested again as part of a citywide effort to stop sensational journalism. By this time, he had given the Polyanthos to someone else, and the charges were eventually dropped.

Later Years and Retirement

Starting in 1842, Dixon took on new jobs. He became an "animal magnetist" (a type of hypnotist) and a "spiritualist" who claimed to have special insights. He also joined public competitions and endurance challenges, becoming a "pedestrian" (a long-distance walker). Dixon's participation in these contests was similar to the dance challenges that became popular later.

In February, he tried to win $4,000 by walking for 48 hours without stopping. When he didn't get the prize, Dixon charged people to watch him. Later that month, he tried to walk for 50 hours. He continued to try many other endurance feats. For example, he stood on a plank for three days and two nights without sleep. In September, he walked back and forth for 76 hours on a 15-foot platform.

Meanwhile, he continued his singing career. In early 1843, Dixon, now called "Pedestrian and Melodist," performed at the Bowery Theatre and with other famous performers. These concerts would be his last.

Despite his adventures in sports and entertainment, Dixon still thought of himself as an editor. He started a new paper called Dixon's Regulator by March and continued his public efforts in New York. In February 1846, he put up posters around the city to announce a meeting to protest certain activities.

During the Mexican–American War, Dixon added timely political references to his song "Zip Coon" and briefly returned to public attention. Another cause seems to have taken Dixon away from New York in 1847. He was likely one of the first Radical Republicans to join a group trying to take over territory in the Yucatán Peninsula to add it to the United States.

Dixon retired to New Orleans, Louisiana, sometime before 1848. A city directory listed his address as "Literary Tent." His obituary said that the Poydras Market was his home and that he had friends who helped him when he was too weak to move. He became sick with a lung illness called tuberculosis in mid-1860. On February 27, 1861, he checked into the New Orleans Charity Hospital, listing his job as "editor." George Washington Dixon passed away on March 2.

Images for kids

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |