Giant squid facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Giant squid |

|

|---|---|

|

|

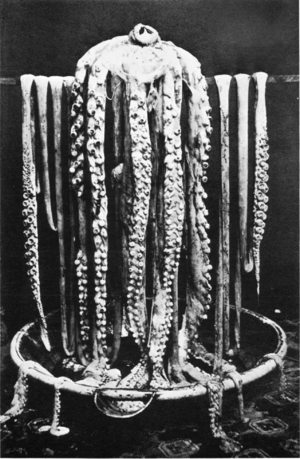

| A giant squid found in Norway in 1954, being measured. | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Order: | Oegopsida |

| Family: | Architeuthidae Pfeffer, 1900 |

| Genus: | Architeuthis Steenstrup in Harting, 1860 |

| Species: |

A. dux

|

| Binomial name | |

| Architeuthis dux Steenstrup, 1857

|

|

|

|

| Where giant squids are found around the world. | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The giant squid (Architeuthis dux) is a huge squid that lives deep in the ocean. It's famous for its incredible size, which is an example of "abyssal gigantism." This means deep-sea creatures often grow much larger than their relatives in shallower waters. Female giant squids can reach about 5 meters (16 feet) from their fins to the tip of their long arms. Males are usually a bit shorter.

While the colossal squid is heavier, the giant squid is longer. Its main body, called the mantle, can be about 2 meters (6.6 feet) long. Its two feeding tentacles, which are usually hidden, can stretch up to 10 meters (33 feet)! Some old stories claimed they were 20 meters (66 feet) or more, but scientists have not confirmed this.

For a long time, scientists wondered if there were many types of giant squid. But recent genetic studies suggest there is only one species worldwide. In 2004, a Japanese team took the first photos of a living giant squid in its natural home.

Contents

The Amazing Giant Squid

What is a Giant Squid?

Scientists group animals to understand them better. The giant squid belongs to a special family called Architeuthidae. Its closest relatives are four other types of "neosquids." Together, these families form a larger group called Architeuthoidea.

Where Do They Live?

Giant squids live in all the world's oceans. They are often found near the edges of continents and islands. You can find them in the North Atlantic, near places like Newfoundland, Norway, and Spain. They also live in the South Atlantic, the North Pacific near Japan, and the Southwest Pacific near New Zealand and Australia. They are rarely seen in very warm or very cold waters.

Scientists are still learning how deep giant squids live. But studies of caught specimens and sperm whale diving habits suggest they can be found between 300 and 1,000 meters (980 to 3,300 feet) deep.

How They Look and Work

Like all squids, a giant squid has a main body (mantle), eight arms, and two much longer tentacles. These arms and tentacles make up most of the squid's length. This makes them lighter than their main predator, the sperm whale. Scientifically measured giant squids weigh hundreds of kilograms, not thousands.

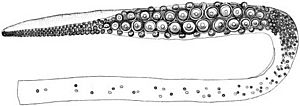

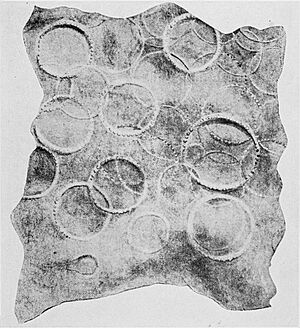

The inside of their arms and tentacles are covered with hundreds of round suction cups. These cups are about 2 to 5 centimeters (0.8 to 2 inches) wide. Each cup has sharp, saw-like rings made of a tough material called chitin. These rings and the suction help the squid grab its prey. You can often see circular scars from these suckers on the heads of sperm whales. This shows where giant squids have fought back.

The ends of the tentacles have special "clubs." These clubs have many suckers, with some larger ones in the middle. At the base of all the arms and tentacles is the squid's mouth. It has a strong, parrot-like beak, just like other cephalopods.

Giant squids have small fins at the back of their mantle. They use these for moving around. Like other cephalopods, they use jet propulsion. They pull water into their mantle and then push it out through a tube called a siphon. This helps them move slowly or quickly. They breathe using two large gills inside their mantle. Their blood system is closed, which is special for cephalopods. Also, like other squids, they can release dark ink.

Their Incredible Eyes

The giant squid has a very advanced nervous system and a complex brain. This makes them very interesting to scientists. They also have some of the largest eyes of any living creature, possibly only smaller than the colossal squid's eyes. Their eyes can be up to 27 centimeters (11 inches) across, with a pupil of 9 centimeters (3.5 inches). Large eyes help them see light in the deep ocean, where it's very dark. They probably can't see colors, but they can likely see small differences in brightness. This is important in their dim habitat.

Staying Afloat

Giant squids stay afloat in the water using a special trick. Their bodies contain a solution of ammonium chloride. This liquid is lighter than seawater, helping them float easily. Most fish use a gas-filled swim bladder to float. This ammonium chloride solution gives giant squid a salty, licorice-like taste. This is why they are not usually eaten by humans.

Like all cephalopods, giant squids have special balance organs called statocysts. These help them know their position and movement in the water. Scientists can tell a giant squid's age by looking at "growth rings" in a part of these organs, similar to counting tree rings. Much of what we know about their age comes from these rings and from beaks found in sperm whale stomachs.

How Big Are They?

The giant squid is the second-largest mollusc and one of the biggest invertebrates alive today. Only the colossal squid is larger by weight. The colossal squid's mantle can be almost twice as long. Some ancient cephalopods, like certain nautiloids, might have been even bigger.

Stories about giant squids being 20 meters (66 feet) or more are common. However, scientists have not found any specimens that big. Experts like Steve O'Shea believe these lengths were likely measured by stretching the tentacles like elastic bands.

After studying many specimens, scientists found that giant squid mantles usually don't grow longer than 2.25 meters (7.4 feet). Including the head and arms (but not the long tentacles), they rarely exceed 5 meters (16 feet). When measured after death, a female giant squid can be up to 12 or 13 meters (39 to 43 feet) long from fins to tentacle tips. Males are usually up to 10 meters (33 feet).

Female giant squids are generally larger and heavier than males. Females can weigh up to 275 kilograms (606 pounds), while males weigh about 150 kilograms (330 pounds).

Their Life Cycle

Scientists don't know much about the giant squid's life cycle. They are thought to become mature around three years old. Males mature at a smaller size than females. Females produce many eggs, sometimes over 5 kilograms (11 pounds) worth. These eggs are tiny, about 0.5 to 1.4 millimeters long.

Females have special organs that produce and prepare their eggs. These organs also create a jelly-like material. This material helps keep the eggs together after they are laid.

Males have organs that produce sperm. This sperm is packaged into special sacs called spermatophores. These sacs are stored in a long sac that ends in a flexible organ. This organ helps transfer the sperm sacs during reproduction. The two lower arms on a male giant squid are specialized to help fertilize the female's eggs.

How sperm is transferred is still a mystery. Giant squids don't have the special arm (hectocotylus) that many other cephalopods use for reproduction. It's thought that the male might inject sperm sacs into the female's arms. This idea came from a female squid found in Tasmania with small tendrils at the base of each arm.

Young giant squids have been found in surface waters near New Zealand and Japan. Scientists hope to study them more to learn about their early life. In December 2015, a young giant squid, about 3.7 meters (12 feet) long, was filmed alive in a Japanese harbor. After many people saw it, a diver guided it safely back into the bay.

What Do They Eat?

Recent studies show that giant squids eat deep-sea fish, like the orange roughy, and other squid species. They catch their prey with their two long tentacles. They grip the prey with the serrated sucker rings on the tentacle ends. Then, they pull the prey towards their powerful beak. They shred the food with a tongue-like organ called a radula, which has small, file-like teeth.

Giant squids are believed to be solitary hunters. This means they hunt alone. Only individual giant squids have been caught in fishing nets. In New Zealand, many giant squids are found near hoki fish. But hoki fish are not part of the squid's diet. This suggests that both giant squids and hoki fish hunt the same smaller animals.

How Many Giant Squids Are There?

Scientists haven't been able to count the exact number of giant squids worldwide. They make estimates by looking at the number of giant squid beaks found in the stomachs of dead sperm whales. Sperm whales are known predators of giant squids.

Based on these observations, it's estimated that sperm whales eat between 4.3 and 131 million giant squids each year. This suggests that the giant squid population is also in the millions. However, getting a more precise number is very difficult.

One Species, Many Names?

For a long time, scientists argued about how many types of giant squids existed. Some thought there could be as many as seventeen different species. Others believed there was only one.

In 1984, a guide to cephalopods said that the different giant squid species were "inadequately described and poorly understood." This meant it was hard to tell them apart. In 2000, marine biologist Mark Norman suggested there were at least three species: one in the Atlantic, one in the Southern Ocean, and one in the North Pacific.

However, in March 2013, researchers at the University of Copenhagen made an important discovery. They studied the DNA of giant squids from all over the world. They found that all giant squids are very closely related genetically. This means that, no matter where they live, they are all part of a single, global population. So, despite earlier ideas, there is only one species of giant squid worldwide.

Giant Squids Through History

People have told stories about giant squids for thousands of years. Aristotle, an ancient Greek thinker, described a large squid he called teuthus over 2,300 years ago. He said they could be as long as 5.7 meters (19 feet). Pliny the Elder, a Roman writer, also wrote about a huge squid. He described its head as "big as a cask" and its arms 30 feet (9 meters) long.

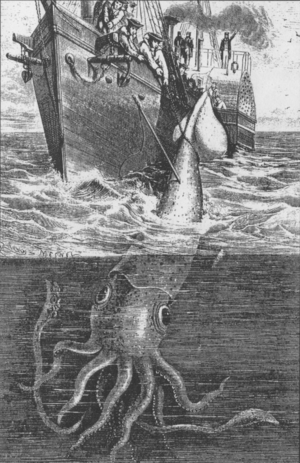

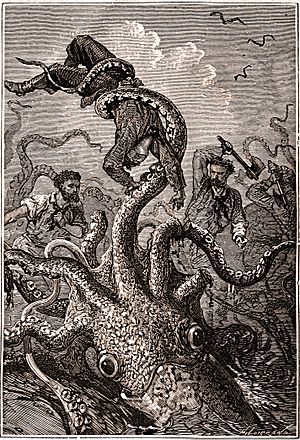

Tales of giant squids were common among sailors. These stories might have inspired the Norse legend of the kraken. The kraken was a huge sea monster with tentacles, said to be as big as an island. It could even sink ships. Some people think the Lusca of the Caribbean and Scylla in Greek mythology also came from giant squid sightings.

In the 1850s, a scientist named Japetus Steenstrup wrote many papers about giant squids. He was the first to use the name "Architeuthus" in 1857. In 1861, a French ship called the Alecton managed to get a piece of a giant squid. This helped scientists around the world recognize the animal.

From 1870 to 1880, many giant squids washed ashore in Newfoundland. For example, one found in 1878 had a mantle 6.1 meters (20 feet) long and one tentacle 10.7 meters (35 feet) long. It weighed about 1,000 kilograms (2,200 pounds). Sadly, many of these specimens were not saved for study. They were often used as fertilizer or animal feed. In 1873, a squid even "attacked" a minister and a boy in a small boat near Bell Island, Newfoundland. Many strandings also happened in New Zealand during this time.

Today, giant squids still wash ashore sometimes, but not as often as in the 19th century. Scientists don't know exactly why they get stranded. It might be because the deep, cold water they live in changes temporarily. Some scientists believe these mass strandings happen in cycles. One expert, Frederick Aldrich, even predicted a small stranding between 1961 and 1968.

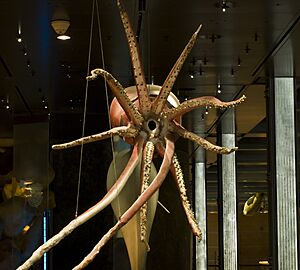

In 2004, another giant squid, nicknamed "Archie," was caught off the Falkland Islands. It was 8.62 meters (28 feet) long. Archie was sent to the Natural History Museum, London to be studied and preserved. It went on display in 2006. Finding such a large, complete specimen is rare. Most found are in poor condition, having washed up dead or been found in sperm whale stomachs.

Preserving Archie was a huge task. It was transported on ice, then carefully defrosted. Scientists had to cover the tentacles in ice packs to stop them from rotting. They also bathed the mantle in water. Then, they injected the squid with a special solution to prevent decay. Archie is now displayed in a 9-meter (30-foot) glass tank at the museum.

In December 2005, the Sea Life Melbourne Aquarium in Australia bought an intact 7-meter (23-foot) giant squid. It was preserved in a huge block of ice. Fishermen caught it off New Zealand's South Island that year.

By 2011, nearly 700 giant squid specimens were known, with new ones reported every year. About 30 of these are displayed in museums and aquariums worldwide. The Museo del Calamar Gigante in Spain once had the largest collection. However, many of its specimens were lost in a storm in 2014.

Scientists are also looking for live young giant squids, including larvae. These young squids look similar to other squid larvae. But they have unique features in their mantle, tentacle suckers, and beaks.

First Photos and Videos

Before the 2000s, the giant squid was one of the few large animals never photographed alive. Marine biologist Richard Ellis called it "the most elusive image in natural history." In 1993, a photo claimed to show a diver with a live giant squid. But it was actually a sick or dying Onykia robusta, not a giant squid. The first video of live (larval) giant squids was captured in 2001. It was shown on a Discovery Channel program.

First images of live adult

The first photo of a live adult giant squid was taken on January 15, 2002. It was found near the water's surface on Goshiki beach in Japan. The squid was about 2 meters (6.6 feet) long in its mantle and 4 meters (13 feet) long overall. It was captured and tied to a dock, where it died overnight. This specimen is now displayed at the National Museum of Nature and Science in Japan.

First observations in the wild

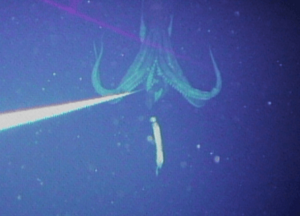

The first photos of a live giant squid in its natural home were taken on September 30, 2004. Tsunemi Kubodera and Kyoichi Mori led the team. They had worked for almost two years to achieve this. They used a small fishing boat and dropped a 900-meter (3,000-foot) line with bait, a camera, and a flash. After many tries, an 8-meter (26-foot) giant squid attacked the lure. The camera took over 500 photos before the squid broke free after four hours. A 5.5-meter (18-foot) tentacle remained attached to the lure. Later DNA tests confirmed it was a giant squid.

On September 27, 2005, Kubodera and Mori shared their photos with the world. The pictures, taken 900 meters (3,000 feet) deep off Japan's Ogasawara Islands, showed the squid attacking the bait. The researchers found the squid's location by following sperm whales. Kubodera said, "we knew that they fed on the squid, and we knew when and how deep they dived, so we used them to lead us to the squid."

These observations showed how adult giant squids actually hunt. The photos showed an aggressive hunting style. This challenged the old idea that giant squids just drifted and ate whatever floated by. The new evidence suggested they are much more active hunters.

First video of live adult in natural habitat

In November 2006, explorer Scott Cassell tried to film a giant squid in the Gulf of California. His team used a special camera attached to a Humboldt squid. This camera-carrying squid filmed what was claimed to be a giant squid, estimated at 40 feet (12 meters) long, hunting. The footage was shown on a History Channel program. However, Cassell later said the documentary had many scientific errors.

In July 2012, a team from NHK and Discovery Channel captured what was called "the first-ever footage of a live giant squid in its natural habitat." The video was shown in January 2013. The team used a special submersible near the Ogasawara Islands, south of Tokyo. The squid was about 3 meters (10 feet) long and was missing its feeding tentacles, possibly from a fight with a sperm whale. They attracted it using artificial light that mimicked glowing jellyfish and a diamond squid as bait. The giant squid was filmed feeding for about 23 minutes before it swam away.

Second video of giant squid in natural habitat

On June 19, 2019, during an expedition by the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Association (NOAA), biologists Nathan J. Robinson and Edith Widder filmed a young giant squid. It was at a depth of 759 meters (2,490 feet) in the Gulf of Mexico. A NOAA zoologist confirmed it was an Architeuthis squid, measuring between 10 and 12 feet (3 to 3.7 meters) long.

Other sightings

Since the 2012 video, other videos of live giant squids have been taken near the surface. One squid appeared in Toyama Harbor, Japan, on December 24, 2015. It was guided back to the open ocean. Most of these sightings near the surface were of sick or dying squids.

Can They Live in Aquariums?

Giant squids cannot be kept in aquariums. This is because they live in very deep, hard-to-reach habitats. Their large size and special needs make it impossible to care for them in captivity. In 2022, a live specimen was found off Japan. An attempt was made to move it to an aquarium, but it was not successful.

Giant Squids in Stories

Giant squids have appeared in many stories and legends. They are often linked to the ancient tales of the kraken. They also feature in famous books like Moby-Dick and Jules Verne's 1870 novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas. More recently, they have appeared in novels like Ian Fleming's Dr. No and Michael Crichton's Sphere.

The image of a giant squid fighting a sperm whale is very common. However, in reality, the squid is usually the whale's prey, not an equal opponent.

See also

In Spanish: Calamares gigantes para niños

In Spanish: Calamares gigantes para niños

- Colossal squid, the largest squid species by mass

- Enteroctopus, a genus whose members are commonly known as giant octopuses

- Giant Squid Interpretation Site, a small museum in Glovers Harbour, Newfoundland

- Gigantic octopus, a hypothesised species of octopus

- Humboldt squid, a large species of squid and the only member of the genus Dosidicus

- Largest organisms

- Taningia danae, a large squid species of the genus Taningia

- Cephalopod attack

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |