Glorious First of June facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Glorious First of June |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the naval operations during the War of the First Coalition | |||||||

Lord Howe's action, or the Glorious First of June, Philip James de Loutherbourg |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,200 killed and wounded |

|

||||||

The Glorious First of June was a huge naval battle fought on June 1, 1794. It was the first major fight between the navies of Great Britain and the French Republic during the French Revolutionary Wars. This battle is also known as the Fourth Battle of Ushant.

The fight happened after a month-long chase across the Bay of Biscay. Both sides had captured smaller ships and had some smaller skirmishes. The British fleet, led by Admiral Lord Howe, wanted to stop a very important French grain convoy (a group of merchant ships traveling together for safety) coming from the United States. This convoy was protected by the French Atlantic Fleet, commanded by Rear-Admiral Villaret-Joyeuse.

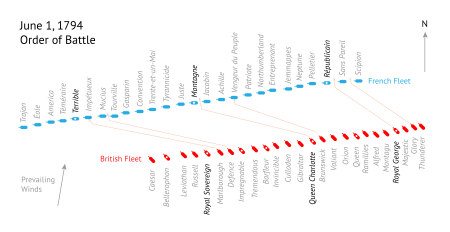

The two fleets finally met in the Atlantic Ocean, about 400 nautical miles (740 km) west of the French island of Ushant. During the battle, Lord Howe tried a new tactic. He ordered his ships to turn directly towards the French line. Each British ship was supposed to "rake" (fire along the length of) and then fight its immediate opponent.

This order was tricky, and not all captains followed it perfectly. Still, the British ships caused a lot of damage to the French fleet. After the battle, both fleets were very damaged. Lord Howe and Villaret-Joyeuse returned to their home ports. Even though France lost seven of its large warships, Villaret-Joyeuse had bought enough time for the vital grain convoy to reach France safely. This was a big win for France.

Both sides claimed victory. The British celebrated capturing ships and controlling the battle area. The French celebrated getting their food convoy safely home. The battle showed some problems in both navies, like captains not always following orders and crews needing more training.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened: A Food Crisis in France

France's Troubles and the Need for Food

Since 1792, France had been at war with its neighbors. By 1793, Britain and the Dutch Republic also declared war on France. Britain was protected by the English Channel, so it focused on naval battles.

The situation in France was difficult in 1794. The country was facing a severe food shortage. A harsh winter and social changes had ruined the harvest. France was at war with all its neighbors, so it couldn't get food from nearby countries.

To solve this, the French government decided to bring food from its colonies overseas and from the United States. A large group of merchant ships gathered in America. These ships would carry the much-needed supplies across the Atlantic to France. The French Atlantic Fleet was ordered to protect this vital food convoy.

The French Navy faced many problems. While their ships were good, the crews were often untrained. Many experienced sailors and officers had been removed or punished during the Reign of Terror. This was a time when many people in France were executed or imprisoned for not being seen as loyal enough to the new government.

This meant that new, less experienced people had to fill important roles. The navy also struggled with getting enough supplies and paying its sailors. In 1793, sailors in Brest even refused to sail because they didn't have enough food.

Villaret de Joyeuse became the new commander of this troubled fleet. He was a skilled leader, but he had to deal with a government official, Jean-Bon Saint-André, who often interfered with his plans. Saint-André reported directly to the government and sometimes made things harder for Villaret.

In contrast, the British Royal Navy was well-prepared for war. Its shipyards were ready to build and repair ships, cannons, and other equipment. The main challenge for Britain was finding enough sailors.

Many new recruits had no experience at sea. Soldiers from the British Army were even drafted to serve on ships. Despite this, the British Channel Fleet had a very skilled commander: Admiral Lord Howe. He was a veteran of many battles.

In the spring of 1794, Lord Howe divided his fleet into three groups. One group escorted British merchant convoys. The main force, with 26 warships, was under Howe's direct command. Their mission was to patrol the Bay of Biscay and find the French food convoy.

The Chase Across the Atlantic: May 1794

The French food convoy left America on April 2. Lord Howe sailed from Portsmouth on May 2 to intercept it. He first checked that the French fleet was still in Brest. Then, he spent two weeks searching the Bay of Biscay for the convoy.

On May 18, Howe returned to Brest and found that the French fleet had sailed the day before. Howe immediately chased Villaret-Joyeuse deep into the Atlantic. Meanwhile, smaller groups of ships from both sides were also at sea, capturing merchant ships.

The French convoy met up with some French warships in the mid-Atlantic. Villaret-Joyeuse, knowing the convoy was close, deliberately sailed west. He hoped to trick Howe into chasing him away from the vital food ships. Howe fell for the trick.

On May 28, Howe finally found Villaret's fleet and attacked. He sent his fastest ships to cut off the French warship Révolutionnaire. This ship fought bravely against six British ships and was heavily damaged. As night fell, the main fleets separated, leaving Révolutionnaire and HMS Audacious still fighting. Both ships eventually made it back to their home ports.

The next day, Howe attacked again. His plan to split the French fleet failed because one of his lead ships didn't follow orders. Both fleets were damaged, but the battle was not decided. However, Howe gained an important advantage: he got the "weather gage." This meant his ships were upwind of the French, allowing him to attack when he chose.

Three French ships were too damaged to continue and returned to port. But the French fleet got stronger the next day when more ships joined them. Thick fog prevented battle for two days. But on June 1, 1794, the fog lifted. The two battle lines were only 6 miles (10 km) apart. Howe was ready for a decisive fight.

The Glorious First of June: The Main Battle

Howe's Bold Plan

On the morning of June 1, Villaret-Joyeuse had tried to get away from the British fleet. But Howe used his advantage of being upwind to close in. By 8:12 AM, the British fleet was just four miles from the French.

The British ships were in a neat line, parallel to the French. Howe then launched his daring plan. Normally, in naval battles of that time, ships would pass each other, firing from a distance. This often didn't lead to many ships being captured or sunk.

Howe wanted a decisive victory. He ordered each of his ships to turn individually towards the French line. The goal was to break through the French line at many points. This would allow British ships to "rake" the French ships. Raking means firing cannons from the front or back of an enemy ship, causing huge damage along its entire length.

After breaking the line, British captains were to position their ships downwind of their opponents. This would cut off the French ships' escape route. Then, they would fight them directly, hoping to force them to surrender. Howe wanted to destroy the French Atlantic Fleet.

Breaking the French Line

As soon as Howe gave the signal and turned his flagship, HMS Queen Charlotte, his plan began to go wrong. Many British captains either didn't understand or ignored the order. They held back, making the British attack uneven. Some ships were also still damaged from earlier fights and couldn't move fast enough.

The French fired on the approaching British ships. But the French fleet's lack of training showed. Many British ships that did follow Howe's order reached the French line without much damage.

HMS Defence was the first British ship to break through the French line. She cut between two French ships, Mucius and Tourville. Defence raked both ships, but then found herself in trouble. The ships behind her didn't follow closely, leaving her vulnerable to attacks from several French ships.

HMS Marlborough also perfectly executed Howe's maneuver. She raked the French ship Impétueux and then got tangled with it. Other British ships had mixed success. Some fought from a distance, while others, like HMS Invincible, charged directly into the French line.

Lord Howe's flagship, HMS Queen Charlotte, led by example. She sailed directly at the French flagship, Montagne. Queen Charlotte passed between Montagne and Vengeur du Peuple, raking both. She then fought Montagne in a close-range cannon duel.

HMS Brunswick also fought fiercely. She tried to cut between two French ships, Achille and Vengeur du Peuple. Brunswick's anchors got tangled in Vengeur's rigging. The two ships were so close that Brunswick's crew had to fire their cannons through closed gunports. They battered each other from just a few feet away.

Chaos and Close Combat

Within an hour, the battle lines were completely mixed up. Three separate fights were happening at once. Ships were damaged, masts were falling, and smoke filled the air.

HMS Bellerophon and HMS Leviathan were in the thick of the action. Bellerophon was badly damaged. A small British frigate, HMS Latona, bravely sailed between the large warships to help Bellerophon, driving off three French ships and towing Bellerophon to safety.

The fight between HMS Brunswick and Vengeur du Peuple was especially brutal. Captain Harvey of Brunswick was badly wounded but refused to leave the deck. The ships fought at point-blank range. Finally, the two shattered ships pulled apart. Both were mostly dismasted and heavily damaged. Vengeur du Peuple was too damaged to move and eventually sank. British boats rescued nearly 500 of her crew.

Other British ships, like HMS Orion and HMS Queen, forced the surrender of French ships like Northumberland and Jemmappes. HMS Royal George and HMS Glory also disabled two French ships, Scipion and Sans Pareil.

Aftermath: Who Won?

Villaret-Joyeuse, on his flagship Montagne, managed to escape the main fighting. He gathered 11 undamaged French ships and formed a new battle line. He tried to attack the damaged British ships, but Lord Howe quickly brought his own ships together to defend them. After a brief exchange of fire, Villaret gave up and sailed east towards France, collecting some of his damaged ships along the way.

The British fleet was too damaged to chase the French. They had many damaged ships and captured French ships to protect. They spent the night making repairs.

The Convoy Arrives Safely

Lord Howe's fleet returned to Britain on June 12. Unbeknownst to him, the vital French grain convoy had finally arrived off France that same day. It had lost only one ship during a storm, meaning the vast majority of the food supplies reached France safely.

Claims of Victory and Awards

Both Britain and France claimed victory. Britain celebrated capturing or sinking seven French ships without losing any of its own. France celebrated because the crucial food convoy had arrived safely.

In Britain, King George III visited the fleet. Many honors were given to the commanders. Admiral Howe was offered more titles but refused. Other admirals received new titles and pensions. All first lieutenants were promoted. A memorial was built for Captains John Hutt and John Harvey, who died from their wounds.

However, there was some disagreement about who deserved awards. Lord Howe's official report listed certain officers for special recognition. This left out many others, causing anger and controversy in the Navy for years. Captain Anthony Molloy of HMS Caesar was accused of not following orders and was removed from his ship.

Of the captured French ships, several were taken into the Royal Navy. The two 80-gun ships, HMS Sans Pareil and HMS Juste, served for many years. The prize money from these captured ships was a huge sum, divided among Howe's fleet.

In France, Villaret-Joyeuse was promoted. The officers of the fleet marched in a parade, celebrating with the newly arrived food supplies. The story of the sinking of Vengeur du Peuple became a legend, with tales of her crew bravely waving the French flag as she went down.

However, many experienced French naval officers were disappointed. They felt Villaret should have fought harder after regrouping his fleet. The French Navy had suffered its worst losses in a single day in over a century. The political changes in France continued to weaken its navy. Poor leadership and lack of training meant the French fleet rarely challenged British naval power again.

Images for kids

-

Lord Howe on the deck of HMS Queen Charlotte 1 June 1794, painted by Mather Brown.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |