Gran conquista de Ultramar facts for kids

The Gran conquista de Ultramar (which means 'Great Conquest Beyond the Sea') is a very old book from the late 1200s. It was written in Old Castilian, a language spoken in Spain a long time ago. This book tells the story of the Crusades, which were a series of religious wars, from 1095 to 1271.

The Gran conquista is a mix of real historical events and exciting legends. Many of its stories come from old French and Occitan poems called chansons de geste. It was created under the direction of King Sancho IV and probably his father, Alfonso X, who were kings of Castile.

Later, the book was translated into Catalan and Galician-Portuguese. Today, parts of it still exist in four old handwritten copies. The first printed version of the book was made in 1503.

Contents

Old Copies and First Prints

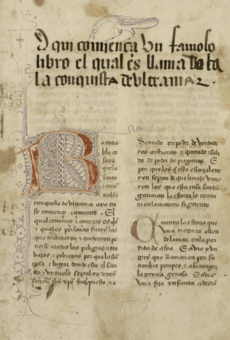

Even though we usually call it Gran conquista de Ultramar, this book also had other names in the old copies, like Grant estoria de Ultramar or Estoria mayor de Ultramar (meaning 'Great History of Outremer').

Today, we have parts of the book in four old handwritten copies, called manuscripts:

- Madrid, BNE ms 1187

- Madrid, BNE ms 1920

- Madrid, BNE ms 2454

- Salamanca, BU ms 1698

These manuscripts were made in the 1300s and 1400s. The Madrid 1187 copy might be as old as 1295. It has spaces for many small pictures, called miniatures, but only two were ever finished.

Sadly, only about 73.5% of the original book's text is found across these four manuscripts. However, the complete book was printed for the first time in 1503 by Hans Giesser in Salamanca. This means about 26.5% of the book is only known because of this 1503 printed version. The first full scholarly edition of the book, which combined the Madrid 1187 manuscript and the 1503 print, was made by Pascual de Gayangos in 1858.

A shorter version of the Gran conquista was also included in another old book, the Galician-Portuguese Crónica general de 1404. This shorter version is found in one manuscript:

- New York, Hispanic Society of America ms B2278

The Gran conquista was also translated into Catalan because King James II of Aragon (who lived from 1264 to 1327) wanted it to be.

Who Wrote It and When?

The Gran conquista was put together from old French and Occitan writings. These were then translated into Castilian. The oldest manuscript (Madrid 1187) has a note at the end, called a colophon, which says King Sancho IV of Castile (who ruled from 1284 to 1295) was the author. However, another manuscript (Madrid 1698) and the first printed edition say Sancho's father, Alfonso X (who ruled from 1252 to 1284), wrote it.

Today, most experts believe that Sancho IV was in charge of choosing, translating, and editing the materials for the book. Some also think that Alfonso X started the work, and Sancho IV finished it after his father died. A note in one manuscript (Madrid 1920) says Sancho IV ordered the translation "from the conquest of Antioch on." This might mean that the part of the book up to the siege of Antioch in 1098 was what Alfonso X had done, and Sancho IV added the rest.

Alfonso X was very interested in the Crusades, especially after Jerusalem was lost in 1244. He even led a crusade against Salé in Africa in 1260. Sancho IV also had his own reasons for the Gran conquista. In 1292, he captured the important city of Tarifa from the Muslims. The stories in the book about how kingdoms rise and fall, and what makes a ruler's power right, might have been very important to Sancho IV's court.

The Gran conquista was finished sometime between 1289 and 1295.

What's Inside the Book?

How the Book is Organized

The Gran conquista tells the story of the Crusades and the history of the Crusader states in the Middle East, known as Outremer, from 1095 to 1271. It starts with an introduction about the Byzantine emperor Heraclius and the rise of Muḥammad. The last event it covers is the Eighth Crusade.

Even though it was put together from many different sources, the book tells one continuous story. It is written in prose (like a normal story), even though some of its original sources were poems.

The Gran conquista is divided into four main parts, called books.

- Book 1 has 231 chapters.

- Book 2 has 265 chapters.

- Book 3 has 395 chapters.

- Book 4 has 429 chapters.

In total, there are 1,320 chapters. No single surviving manuscript has all of them; the most any manuscript has is 561 chapters.

Where the Stories Came From

The main part of the Gran conquista is a translation of a French book called the Estoire d'Eracles. This French book was itself a translation of a Latin history book by William of Tyre called Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum. The Estoire d'Eracles covered history up to 1184, but many parts were added to it in the 1200s. The version used for the Gran conquista included a continuation called the Chronique d'Ernoul et de Bernard le trésorier, which brought the history up to 1229. About 1,100 of the chapters in the Gran conquista are based mostly on the Estoire.

The stories from the Estoire were made more exciting by adding parts from various French epic poems and an Occitan poem called Canso d'Antioca. Some of the French poems used include Berte aus grans pies, Mainet, and several from a group of poems about the Crusades, such as Naissance du chevalier au cygne, Chevalier au cygne, Enfances Godefroi, Chanson d'Antioche, Chanson des chétifs, and Chanson de Jérusalem. About one-third of the entire Gran conquista comes from these old French epic poems.

Fictional Stories in the Book

One of the most special things about the Gran conquista is that it includes the fictional story of the Swan Knight within a historical work. This was not entirely new, as other old Spanish histories also included legendary tales.

Experts like Cristina González suggest that the Swan Knight is like a perfect example of a knight. She explains that in the Gran conquista, the success or failure of the Christians in the Holy Land depends on whether they follow the example of the Swan Knight and his grandson, Godfrey of Bouillon. This helps to explain why they had so many sad defeats and also gives a way to achieve the victories they wanted.

Because of this, the book can be called a "chivalric chronicle" or a "romanced chronicle" (crónica novelesca). It even served as a model for later stories about knights, like Amadís de Gaula. The 1503 printed edition had many features that made it look like a romance novel, which led many scholars to think of the book as mostly fiction.

See also

Template:Kids robot.svg In Spanish: Gran conquista de Ultramar para niños