Graybar Building facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Graybar Building |

|

|---|---|

Viewed from a building to the northeast, across the intersection of 44th Street and Lexington Avenue

|

|

| General information | |

| Type | Office |

| Architectural style | Art Deco |

| Location | 420–430 Lexington Avenue, Manhattan, New York |

| Coordinates | 40°45′09″N 73°58′33″W / 40.752626°N 73.975700°W |

| Construction started | 1925 |

| Completed | 1927 |

| Owner | SL Green Realty |

| Height | |

| Architectural | 351 feet (107 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 30 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | John Sloan |

| Architecture firm | Sloan & Robertson |

| Developer | Graybar |

| Engineer | Clyde R. Place |

| Main contractor | |

| Designated: | November 22, 2016 |

| Reference #: | 2554 |

The Graybar Building, also known as 420 Lexington Avenue, is a 30-story office building in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. It stands at 420–430 Lexington Avenue, between 43rd and 44th Streets. The building is right next to the famous Grand Central Terminal.

Sloan & Robertson designed the Graybar Building in the Art Deco style. It was built as part of "Terminal City". This was a group of buildings constructed above Grand Central's underground train tracks. This means the Graybar Building uses the space, or "air rights", above these tracks. Inside, the ground floor has the "Graybar Passage". This is a public walkway connecting Lexington Avenue to Grand Central Terminal.

Construction began in 1925, and the building was first called the Eastern Terminal Office Building. It was renamed the next year after Graybar, one of its first major tenants. The Graybar Building opened in April 1927. It quickly became fully rented in less than a year. The building has changed owners several times. The current owner, SL Green Realty, bought it in 1998. In 2016, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission made the Graybar Building an official city landmark.

Contents

Where is the Graybar Building located?

The Graybar Building is on Lexington Avenue to the east. The Park Avenue Viaduct is to its west. It stretches from 44th Street in the north to 43rd Street in the south. The western side of the building faces Depew Place. This alley was created when the first Grand Central Depot was built. Today, it is still used as a driveway for a nearby post office.

What was on the site before?

In 1871, the New York Central Railroad built the Grand Central Depot. This was a train station at ground level. Later, in 1900, it was replaced by Grand Central Station. The land where the Graybar Building now stands was partly home to the first Grand Central Palace. This building was constructed around 1893 and later became a hotel. There was also a small post office on the site.

In 1902, a train crash in the Park Avenue Tunnel killed 15 people. This led to plans for a new underground terminal. The land for the Graybar Building was bought by New York Central in 1904. A temporary train terminal was built under the old Palace. The original Palace was torn down by 1913. This made way for the construction of Grand Central Terminal. The terminal's post office, the Commodore Hotel New York, and the Graybar Building now stand on that site.

Building Grand Central Terminal led to fast growth in the surrounding areas. Property prices went up a lot. By 1920, the area was seen as a "great civic centre." The site for the Graybar Building was cleared before 1919. It was meant for the post office, but the Graybar Building itself was not yet planned.

How was the Graybar Building designed?

Sloan & Robertson designed the Graybar Building in the Art Deco style. Clyde R. Place was the main engineer. The building is officially at 420 Lexington Avenue. It also covers the lots from 420 to 430 Lexington Avenue. The Graybar Building is 351 feet (107 m) tall and has 30 stories. It has about 1.35 million square feet (125,000 m2) of floor space.

The Graybar Building was one of many buildings built near Grand Central Terminal after 1913. Grand Central's train tracks and platforms were underground. This was different from the older stations. The terminal's construction was partly paid for by selling the "air rights" above the tracks. These areas were called Terminal City. In the 1990s, there were ideas to build another building on the Graybar site. This was to use extra air rights from Grand Central. A 2012 plan to rezone East Midtown also brought up using these air rights. This led to the Graybar Building becoming a city landmark in 2016. This was done to protect it from being torn down for new development.

What is the building's shape?

Unlike older buildings in Terminal City, the Graybar Building has less decoration. It was built with setbacks and "light courts." This was to follow the 1916 Zoning Resolution. The western part of the building looks like a capital "H." The eastern part has two arms reaching east from the "H," making it look like a "C." The "H" and "C" create three light courts. There are two courts on the western side, facing north and south. There is also a 70 feet (21 m)* east-facing court on the eastern side. These courts mean that most of the building's floor space is near a window. The building has over 4,300 windows.

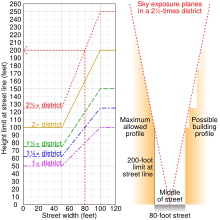

The 1916 Zoning Resolution required the building to have setbacks. These are steps back from the street on the 15th, 17th, 19th, and 23rd floors. This rule was made to let light reach the streets and the lower floors of tall buildings. The sides of the building do not have setbacks. The north side faces a shorter part of the Graybar Building. The south side faces Grand Central Market. The west side faces Depew Place and the Park Avenue Viaduct.

What does the outside look like?

The Graybar Building's outside, or facade, is mostly plain, except at the bottom. It is made of brick and Indiana Limestone. The base is made of limestone. Some window panels have black brick. These create "subtle vertical bands" that make the building look taller. Near the top of the facade facing Lexington Avenue are four gargoyle-shaped water spouts.

What are the entrance areas like?

The Graybar Building has three main entrances from Lexington Avenue. The southernmost entrance leads to the Graybar Passage. This passage connects to Grand Central Terminal. This entrance has three sets of doors, each with its own marquee. The middle doors have a marquee supported by three metal bars. The side door marquees have two bars. Metal figures of rats are on these bars. They are shown running upwards. The architect, John Sloan, said in 1933 that these rats showed New York City as a "great transportation centre and a great seaport." These rat sculptures were removed in the 1990s but put back during a renovation.

The central entrance has a carving that says "GRAYBAR BUILDING." It also shows two "winged guardian creatures." Outside each entrance are pairs of figures, each 20 feet (6.1 m) tall. The figures at the south entrance represent air and water. The north entrance figures represent earth and fire. The central entrance figures symbolize electricity and transportation. Rays of light are shown coming from their heads. Other decorations at the base include metal-and-glass lights. Sloan said these features were meant to give an "eastern" feel. Above the central entrance is a 65 feet (20 m)* flagpole with colorful designs at its base.

The northern entrance at 44th Street was planned as a third way in. However, it was never used. It was meant to connect to a north-south hall. This hall would have led from Grand Central to a planned expansion of the post office next to the Graybar Building.

What is the inside like?

Ground level

The southernmost entrance leads to the Graybar Passage. This is one of three walkways connecting Grand Central to Lexington Avenue. It was built on the first floor of the Graybar Building in 1926. The passage has a 28 feet (8.5 m) ceiling. It is mostly 40 feet (12 m) wide, widening to 60 feet (18 m) at its western end. There are no stores along the passage to prevent crowds. Three gates lead from the north side of the passage to six train tracks. Its walls are made of travertine, and the floor is terrazzo. The ceiling has seven groin vaults, each with a bronze chandelier. Two vaults are painted with cumulus clouds. The third has a 1927 mural by Edward Trumbull showing American transportation.

The central entrance leads to an elevator lobby for tenants. Another hallway connects this lobby to the Graybar Passage. The northern part of the ground floor had a bank. The ground floor also included an extension of the Grand Central post office.

Basement and underground areas

The building used 25,000 short tons (23,000 t) of steel and about 31 and 36 acres (13 and 15 ha) of concrete. Both the building and the tracks below it have foundations connected to the rock underground. Even though they have separate structures, train vibrations could still affect the building. To stop this, a sheet of lead was put into a special concrete "mat" that absorbs vibrations. The building's steel frame was then anchored to this "mat."

The basements are an extension of Grand Central Terminal. Their construction was paid for by the New York Central Railroad. The basements hold several tracks and platforms. They also have break rooms for the "red cap" porters (people who help carry luggage) at Grand Central. The terminal's M42 electrical substation is also there. Twelve tracks on the terminal's lower level were made longer when the Graybar Building was built. The porters' rooms included locker rooms, a kitchen, a restaurant, and other services. The M42 substation is about 100 feet (30 m) below the Graybar Building's ground level. It opened in 1930. West of the substation are many other facilities. These include storage rooms, a coal area, and shops for various workers. Elevators on the south side of the Graybar Passage lead to the basement.

Former subway passage

An underground passage from the New York City Subway's Grand Central–42nd Street station used to lead to the Graybar Building's southern entrance. This 120 feet (37 m)* passage connected to another hallway. That hallway led to the Chrysler Building to the east. In 1991, the New York City Department of City Planning suggested closing the passage. It was not used much and was close to other connections. For safety reasons, the Graybar subway passage and 14 others were closed by the New York City Transit Authority on March 29, 1991. The passage was behind a ticket booth, making it hard to watch. It was described as "deceptively long and treacherous."

What is the history of the Graybar Building?

How was the building planned and built?

In August 1925, a company called Eastern Offices Inc. announced plans to build a 30-story tower. It would be the "largest office building in the world" and cover the entire site. Eastern Offices signed a deal to lease the land from New York Central for 21 years. This lease could be renewed twice, for a total of 63 years. The agreement said the building must have walkways to the terminal and the subway station. It also had to have "high-grade" office space and other facilities for New York Central. Eastern Offices was part of the Todd, Robertson and Todd Engineering Corporation. This group later helped build Rockefeller Center.

The building was first called the Eastern Terminal Office Building. In May 1926, the Graybar Electric Company rented the 15th floor. The president of Graybar was friends with one of the partners from Todd, Robertson, and Todd. Another company, J. Walter Thompson, had rented more floors but did not want the naming rights. So, the project became known as the Graybar Building.

The building's construction permit was given in 1925. It was expected to cost $12.5 million. Digging began in early 1925, going down 90 feet (27 m). A train track (track 200) looped under the site and had to stay open. So, it was moved to a temporary raised structure. By May 1926, the building's steel frame was being put up. Much of the 25,000 short tons (23,000 t) of steel was underground because of the complex train tunnels. By August 1926, the steel was near "street level." The last steel piece was put in place on October 8, 1926.

Newspapers wrote about the building's progress and size. A Brooklyn Daily Eagle article in September 1926 said the building had "nearly 31 acres (13 ha) of concrete floors." The Brooklyn Times-Union said that if there was one person per 100 square feet (9.3 m2) in the Graybar Building's 1,350,000 square feet (125,000 m2) of office space, it would be the 43rd largest place in New York state. The Eagle also wrote about how lead in concrete would reduce train vibrations. Bricks and concrete floors were installed starting in late 1926. By early 1927, about 1,100 workers were finishing the inside. This included installing 5,000 doors. Edward Trumbull also finished the murals in the Graybar Passage. By March, the offices were ready for tenants.

How has the building been used over the years?

When it was finished, the Graybar Building was called the world's largest office building. It had space for over 12,000 office workers. The first tenants moved in April 1927. By January 1928, all the building's space was rented.

The Graybar Building and the nearby Chrysler Building were sold together in 1953 for $52 million. This was reported to be the biggest real estate sale in New York City's history at the time. In 1957, the Chrysler Building and the Graybar Building were sold again for $66 million. This set a new record.

Graybar Electric Company moved its headquarters out of the building in 1982. In 1998, SL Green Realty bought the lease for the building for $165 million. At that time, 20% of the building was empty. SL Green planned to spend $8 million to renovate it. The Graybar Passage in Grand Central Terminal was also being renovated then. The building's renovations included a new entrance, lobby, and cleaned outside walls. Ceilings, floors, and restrooms were also updated. In November 2016, the Graybar Building and ten other nearby buildings became official historic landmarks.

Who are the tenants?

By 1927, all the spaces in the Graybar Building were rented. This showed that "high-class office tenants" were willing to move to Lexington Avenue. One of the first tenants was the publisher Condé Nast, which rented the 19th floor in 1925. The building's namesake, Graybar Electric Company, used the 15th floor. The advertising company J. Walter Thompson rented even more space. A Chase Bank branch was in the northern part of the ground floor. It was designed without the usual teller cages. The Condé Nast magazines Vanity Fair, Vogue, and House & Garden also had offices there. Other early tenants included Remington Rand, Turner Construction, YMCA, and the Associated Architects who designed Rockefeller Center.

Today, tenants in the Graybar Building include the Metro-North Railroad, Metropolitan Transportation Authority, New York Life Insurance Company, and DeWitt Stern Group. The current owner, SL Green, also has offices in the building.

See also

In Spanish: Graybar Building para niños

In Spanish: Graybar Building para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |