History of Grand Central Terminal facts for kids

Grand Central Terminal is a huge train station in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. It serves the Metro-North Railroad's Harlem, Hudson, and New Haven lines. This famous building is actually the third train station built on the same spot.

The current Grand Central Terminal was built by the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad. It also served the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad. Even today, trains continue to use it under new railroad companies.

The idea for Grand Central Terminal came from a need for one main station for three different railroads in Midtown Manhattan. In 1871, a powerful businessman named Cornelius Vanderbilt built the first station, called Grand Central Depot. It served the New York Central & Hudson River, New York and Harlem, and New Haven railroads.

Because more and more people were using the station, it was rebuilt and renamed Grand Central Station by 1900. The current building was designed by the companies Reed and Stem and Warren and Wetmore. Its construction began in 1903 and it officially opened on February 2, 1913. This happened after a train crash in 1902 showed the need for safer electric trains.

Grand Central Terminal kept growing until after World War II, when fewer people started traveling by train. In the 1950s and 1970s, there were plans to tear down Grand Central, but luckily, they didn't happen. The terminal was given special landmark protection during this time. The station was improved a little in the 1970s and 1980s, then had a big makeover in the 1990s.

From 1913 to 1991, Grand Central was also a major station for long-distance trains. In 1991, all long-distance train services moved to Penn Station, another big train station nearby. A new project, called East Side Access, will bring Long Island Rail Road trains to a new station underneath Grand Central Terminal. This project is expected to be finished in late 2022.

Contents

- Early Train Stations in New York City

- Grand Central Depot: The First Station

- Grand Central Station: The Second Station

- Building the New Grand Central Terminal

- Grand Central's Early Years (1910s–1940s)

- Grand Central's Later Years (1950s–1980s)

- Grand Central's Big Restoration (1990s)

- Grand Central in the 21st Century

- Events and Exhibitions

- Images for kids

Early Train Stations in New York City

Grand Central Terminal was built because there was a need for a main train station. This station would serve the Hudson River Railroad, the New York and Harlem Railroad, and the New York and New Haven Railroad. These lines all met in what is now Midtown Manhattan.

The Harlem Railroad was the first to start operating in 1831. By 1837, its tracks reached Harlem, in upper Manhattan. The very first railroad building on the site of Grand Central Terminal was a maintenance shed for the Harlem Railroad. It was built around 1837.

The Harlem Railroad used to run on street level along Fourth (now Park) Avenue. But laws were passed that stopped steam trains from running in Lower Manhattan. So, the railroad's southern end moved north to 26th Street. In 1857, the New Haven Railroad built a station next to the Harlem Railroad's. They shared a rail yard, which was the start of the idea for a central station used by different train companies.

The Hudson River Railroad ran separately on the west side of Manhattan. It ended at Tenth Avenue and 30th Street. When the city banned steam trains below 42nd Street around 1857–1858, the Harlem and New Haven Railroads' station moved there. The Hudson River Railroad stayed on the west side, away from the busy east side.

Cornelius Vanderbilt, a powerful businessman, started buying stock in the Harlem Railroad in 1863. By the next year, he also controlled the Hudson River Railroad. He wanted to combine the railroads. In 1869, he merged them into the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad. He then built a connecting line to link them.

Vanderbilt wanted to bring all three railroads together at one central station. This would replace the separate stations that caused confusion. The three lines would meet in Mott Haven, then use the Harlem Railroad's tracks along Park Avenue to a new main station at 42nd Street.

Grand Central Depot: The First Station

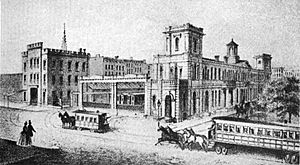

By 1869, Vanderbilt hired John B. Snook to design his new station, called Grand Central Depot. It was built on the site of the 42nd Street depot. At the time, this area was far outside the developed city.

Construction began on September 1, 1869, and the depot was finished by October 1871. The project also created Vanderbilt Avenue, a road next to the station. To avoid confusion, the railroads started using the new station on different dates.

What the Depot Looked Like

The station had a three-story main building and a large train shed. The main building had passenger areas on the ground floor and railroad offices upstairs. The train shed was a huge glass structure, about 530 feet long and 200 feet wide. Its roof was 100 feet high.

The train shed's roof had 32 arches over the tracks. There were three waiting rooms, one for each railroad. The station was 695 feet long along Vanderbilt Avenue and 530 feet along 42nd Street. It was considered the largest open space in the United States. It was also the biggest train station in the world, with 12 tracks that could hold 150 train cars.

Grand Central Depot had some new features. It had high-level platforms, which were level with the train car floors. The train shed had a "balloon roof" that stretched over the tracks without support columns. Inspectors only allowed people with tickets onto the platforms. The station also had four restaurants, a billiards room, shops, and a police station.

Changes and Improvements

The tracks leading to the new station caused problems. Accidents happened often at the street crossings along Fourth Avenue. Seven people died within 12 days of the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad moving to Grand Central. In 1872, Vanderbilt suggested the Fourth Avenue Improvement Project. This project moved the tracks underground between 48th and 97th streets. The improvements were finished in 1874. This allowed trains to go underground into the new depot. Fourth Avenue was also renamed Park Avenue.

Train traffic at Grand Central Depot grew very quickly. By the mid-1880s, its 12 tracks were full. In 1885, a seven-track addition was built on the east side of the station. This addition handled passengers arriving in New York City. The original building handled trains leaving the city. The train yards were also made bigger.

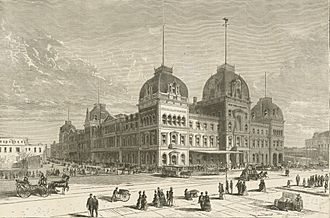

Grand Central Station: The Second Station

By 1897, Grand Central Depot was full again, with 11.5 million passengers a year. To handle the crowds, the railroads made the main building bigger, from three to six stories. They also enlarged the main hall and waiting rooms. The train yard was changed to help trains move faster.

The rebuilt building was renamed Grand Central Station. The new waiting room opened in October 1900. However, people started to criticize the station for being dirty. In 1899, The New York Times newspaper called it "discreditable."

The 1902 Train Crash and Its Impact

As train traffic increased, so did the problem of smoke and soot from steam trains in the Park Avenue Tunnel. This tunnel was the only way to reach the station. In 1899, the New York Central's chief engineer, William J. Wilgus, suggested using electric trains. But the railroad thought it was too expensive.

On January 8, 1902, a southbound train crashed into another train in the smoky Park Avenue Tunnel. This accident killed 15 people and injured more than 30. A week later, New York Central's president announced that all train lines leading to Grand Central would be electrified. The approach to the station would also be put underground. The state government then passed a law banning all steam trains in Manhattan starting July 1, 1908.

By December 1902, New York Central agreed to put the tracks from 46th to 59th Streets underground. They would also upgrade the tracks for electric trains. Wilgus suggested that electric trains were cleaner, faster, and cheaper to fix. He also said that if the tracks were underground, the railroad could build new buildings on top of the covered area along Park Avenue.

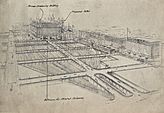

Wilgus also proposed replacing the two-year-old station with a new, two-level electric train terminal. This new terminal would have a larger train yard and special tracks that would allow trains to turn around easily. To help pay for the huge cost, he suggested building a 12-story building above the terminal. The rent from this building would bring in a lot of money.

In March 1903, Wilgus presented a more detailed plan. It included separate levels for local and long-distance trains, a large main hall, and connections to the subway. The railroad's board of directors approved the $35 million project in June 1903. Most of Wilgus's ideas were eventually built.

Building the New Grand Central Terminal

The entire old building was torn down in stages and replaced by the current Grand Central Terminal. It was planned to be the biggest terminal in the world, both in size and number of tracks.

Designing the New Station

The new Grand Central Terminal was meant to compete with Pennsylvania Station, another fancy electric-train station being built on Manhattan's west side. In 1903, New York Central asked four well-known design firms to compete for the job.

The railroad chose the design by Reed and Stem, who were good at designing train stations. They suggested roads for cars around the terminal and ramps between its two passenger levels. Warren and Wetmore were also chosen to help design the building. The design also included using the space above the tracks for new buildings.

The two design companies, called Associated Architects of Grand Central Terminal, had a difficult relationship. They often argued about the design. Warren and Wetmore removed the 12-story tower and car roads that were part of Reed and Stem's plan. The New Haven Railroad, which paid one-third of the project's cost, also didn't like the tower being removed because it would mean less money from rents. They also thought Warren's design was too expensive.

The New Haven Railroad finally approved the design in December 1909. They agreed to include foundations for a future building above Grand Central Terminal. The elevated roads were also put back into the plan. Charles Reed died in 1911. After his funeral, Warren and Wetmore secretly met with New York Central and took full credit for the station's design. Reed and Stem later sued Warren and Wetmore and won.

Before building, the architects tested different parts of the design. They built ramps with different slopes and watched people of all ages walk on them. They chose an 8-degree slope, which was gentle enough for a child to walk easily. They also tested different types of stone in Van Cortlandt Park to find a strong stone for the outside of the building. They chose Indiana Limestone.

Starting Construction

William J. Wilgus, who was in charge of the project, planned to build the new terminal in sections. This way, train service wouldn't be stopped. Construction on Grand Central Terminal began on June 19, 1903.

The construction project was huge. About 3.2 million cubic yards of dirt were dug out, some as deep as 10 stories. Over 10,000 workers installed 118,597 tons of steel and 33 miles of track. Waste was carried away by train to a landfill. Workers often stopped to let trains pass. Rock blasting for digging could only be done at night. Even with the huge scale of the project, no pedestrians were hurt during construction.

The first section of construction required tearing down over 200 buildings. This forced hundreds of people to move from their homes. The construction company fell behind schedule. The first section was mostly finished in 1907.

Building the station section by section doubled the cost. At first, the project was supposed to cost $40.7 million. But the cost grew to $59.9 million in 1904 and $71.8 million in 1906. The total cost, including electrification and developing Park Avenue, was estimated at $180 million in 1910. The terminal itself was expected to cost $100 million.

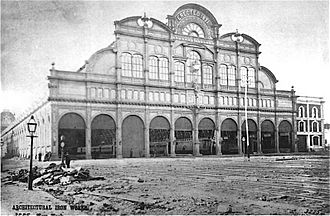

Finishing the Terminal

The New York Central Railroad tested electric trains in 1904. They found the trains were fast enough for Grand Central. Over the next few years, the New York Central and New Haven Railroads electrified their tracks. This allowed electric trains to enter Grand Central Terminal when it was finished. The first electric train left for the old Grand Central Station on September 30, 1906.

Work on the train yard was slow. This was because of the small size of each section and the difficulty of designing two levels with different track layouts. The upper level was covered in 1910. North of the station, Park Avenue and nearby streets were raised onto bridges above the tracks.

The last train left Grand Central Station at midnight on June 5, 1910. Workers immediately began tearing down the old station. The design of the new station was not finalized until 1910. In January 1911, the railroad submitted 55 blueprints for the new station building. The last tracks from the old Grand Central Station were removed on June 21, 1912.

Grand Central's Early Years (1910s–1940s)

On February 2, 1913, the new Grand Central Terminal officially opened. Passengers boarded the first train just after midnight. The building was almost finished, though some additions, like the Glory of Commerce statue, were added later in 1914.

The terminal helped develop the area around it, especially a business district called Terminal City. This area was built above the covered train tracks. Land values along Park Avenue and in Terminal City more than tripled between 1904 and 1926. Terminal City included office buildings like the Chrysler Building, fancy apartment buildings, and hotels. The Commodore Hotel opened in 1919.

The new electric trains and Grand Central Terminal helped create wealthy suburbs north of the city. People with money often traveled to places like Greenwich or Larchmont, which had direct electric train service from Grand Central.

After Grand Central Terminal opened, the number of passengers grew a lot. In 1913, it handled 22.4 million passengers. By 1920, 37 million passengers used the station. However, after 1919, Penn Station usually had more passengers than Grand Central. Even so, Grand Central's development led to fast growth in New York City's northern suburbs.

During World War I, flags were hung in Grand Central Terminal to honor railroad employees fighting in the war. One flag honored 4,976 New York Central employees.

In 1918, New York Central suggested making Grand Central Terminal even bigger. Passenger numbers kept growing, and by 1927, the terminal saw 43 million passengers each year. Small improvements were made in the 1920s and 1930s, like new passageways and a newsreel theater. By 1938, the terminal served 100,000 passengers and 300,000 visitors on an average weekday.

During the Great Depression, fewer people rode trains. The railroad also had a lot of debt from building Grand Central Terminal and Terminal City.

Connected Buildings and Services

When Grand Central Terminal opened, it had a direct connection to the nearby subway station. The subway platforms were part of the original New York City Subway, which opened in 1904.

The Grand Central Art Galleries opened in the terminal in 1923. They were run by a group of artists. The galleries took up most of the terminal's sixth floor and had eight exhibition rooms. A year later, the Grand Central School of Art opened on the seventh floor. The school stayed there until 1944. In 1958, the art galleries moved out of the terminal.

A power and heating plant was built with the terminal. It provided power to the tracks, the station, and nearby buildings. By the late 1920s, the plant was not needed as much. It was torn down starting in 1929 and replaced by the Waldorf Astoria New York hotel.

J. P. Carey & Co. Shops

In 1913, a businessman named J. P. Carey opened a small shop in the terminal. His business grew to include a barbershop, laundry, shoe store, and clothing shop, all called J. P. Carey & Co. In the 1920s, Carey also started a limousine service. Later, he added bus service to the city's airports. These businesses were very successful because of their location. Carey's shops showed affordable items with prices, which was unusual for terminal shops at the time.

Carey stored his goods in an unfinished, underground part of the terminal. Railroad employees called this area "Carey's Hole." The name is still used today, even though the space is now a lounge for railroad employees.

Grand Central During World War II

During World War II, many troops traveled through the terminal. More ticket offices were opened. An organist named Mary Lee Read, who played in the terminal, would sometimes stop commuter traffic when she played the U.S. national anthem. She was later asked not to play it to avoid delays. Retired employees came back to work, and women were trained as ticket agents for the first time.

Because Grand Central was so important for travel during the war, its windows were covered with blackout paint. This was to prevent enemy planes from easily seeing the building.

A large mural was put on the Main Concourse's east wall in 1941 to encourage people to buy war bonds. This mural was replaced by another in 1943. A big flag also hung in the Main Concourse, honoring the 21,314 New York Central Railroad employees who served in the war.

The terminal also had a canteen for service members, with pool tables, a piano, and food counters. The terminal was also used for military funeral processions.

Grand Central's Later Years (1950s–1980s)

Plans to Change the Station

Grand Central's passenger numbers reached their highest point in 1946, with over 65 million passengers. But then, fewer people started using trains because of airplanes and new highways. By the 1950s, passenger numbers dropped so much that there were plans to tear down and replace the station.

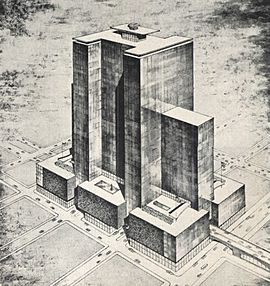

In 1954, New York Central looked at plans to replace the terminal with a skyscraper. The railroad was losing money and wanted to sell the space above the building. One plan was for a 55-story building. Another plan, by I. M. Pei, was for a 108-story glass tower. These plans caused 235 architects to write letters asking to save the terminal. Neither of these designs was built.

By 1958, New York Central even suggested closing Grand Central Terminal. But it remained a busy place. In 1960, the terminal had over 2,000 employees, including its own fire team and police force.

In 1955, the railroad invited developers to suggest ways to rebuild the terminal. A developer proposed a 65-story tower to replace a baggage building. A smaller 50-story tower was approved in 1958. This tower became the Pan Am Building (now the MetLife Building), which opened in 1963.

Protecting Grand Central

Another idea in 1960 was to turn the upper part of the Main Concourse into a three-story bowling alley. This idea was very unpopular, and people called it a "desecration." The city stopped the plan in 1961.

The Pan Am Building saved the terminal from being torn down right away. But New York Central continued to struggle. In 1968, it merged with the Pennsylvania Railroad to form Penn Central. The Pennsylvania Railroad had already started tearing down its old Penn Station in 1963. This led to the creation of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, which made Grand Central Terminal a protected city landmark in August 1967.

In February 1968, plans were announced for a new tower over the terminal, designed by Marcel Breuer. This tower would have been 950 feet tall. It would have saved the Main Concourse but destroyed the southern part of the terminal for elevators and a taxi area.

These plans faced huge opposition from the public. Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, the former First Lady, spoke out against it. She said it was "cruel to let our city die by degrees, stripped of all her proud monuments."

Penn Central changed the plan in June 1969, making the building smaller. But because Grand Central was a landmark, the Landmarks Preservation Commission stopped Penn Central from building either of Breuer's designs. The railroad sued the city. In 1978, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in favor of the city. This decision stopped Penn Central from building the proposed tower.

Changes in Ownership and Improvements

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) started leasing the Penn Central tracks in 1965. The MTA took over full operations of the Harlem, Hudson, and New Haven Lines in 1983, forming the Metro-North Railroad.

Grand Central and the area around it became run down. The inside of Grand Central was covered with huge advertisements. The most famous was the giant Kodak Colorama photos.

In 1975, real estate developer Donald Trump bought the Commodore Hotel next to the terminal. He worked with a hotel company to turn it into the Grand Hyatt New York. Trump agreed to renovate the outside of the terminal as part of the deal. The Grand Hyatt opened in 1980, and the area began to change.

A new passageway was opened in Grand Central in May 1975 to help people move around better. Grand Central Terminal was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1975 and became a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

In the early 1980s, plans were made for new passageways at the northern end of the station. This project, later called Grand Central North, would be the first major expansion since 1913. The MTA also did some restorations in the late 1980s before the terminal's 75th anniversary in 1988. They fixed the roof, cleaned marble floors, and removed blackout paint from the skylights.

In 1988, Amtrak announced it would stop serving Grand Central. This was because a new connection on Manhattan's West Side would allow trains to use Penn Station instead. Amtrak had to pay the MTA a lot of money to use the tracks to Grand Central. The last regular Amtrak train left Grand Central on April 7, 1991. Since then, Grand Central has mostly served Metro-North Railroad.

Grand Central's Big Restoration (1990s)

Planning the Renovation

In 1988, the MTA studied Grand Central Terminal. The study suggested that parts of the terminal could be turned into shops and restaurants. This would increase the terminal's income from retail and advertising. At the time, over 80 million passengers used Grand Central every year, but many shops were empty. A big renovation was estimated to cost $400 million.

By December 1993, the MTA was planning to lease Grand Central Terminal for 110 years. This was part of an agreement to renovate the terminal. The amount of retail space was increased. In 1995, the MTA announced a $113.8 million renovation, the biggest in the terminal's history. The renovation was expected to be finished in 1998.

The Renovation Work

During the 1995 renovation, all billboards were removed, and the station was restored. Work also began on Grand Central North, the new system of passageways. The most amazing part of the project was cleaning the Main Concourse ceiling. This revealed the beautiful painted sky and constellations that had been hidden by years of grime.

The renovation also included building the East Stairs. This curved staircase on the east side of the station matched the West Stairs. The original architects had planned for these stairs, but they were never built. The stone for the new staircase came from the same quarry in Tennessee that provided the original stone. Each new piece of stone was marked to show it wasn't part of the original building.

The waiting room was also restored and cleaned. Other changes included a complete overhaul of the building's structure and replacing the old train information board with a new electronic one.

The project involved cleaning the outside of the building, fixing cracks, and repairing the copper roof. The large windows of the Main Concourse were repaired, and the blackout paint from World War II was removed. A 4,000-pound cast-iron eagle from the old Grand Central Depot was returned and placed above a new entrance. The renovation also almost doubled the terminal's retail space. The goal was to make the terminal's inside look like it did in 1913.

An official ceremony was held on October 1, 1998, to celebrate the finished interior renovations. The project ended up costing $196 million. The New York Times praised the restoration but worried that the MTA was turning the terminal into too much of a shopping mall. The Grand Central North passageways opened on August 18, 1999. The total cost was $250 million.

In 1998, after the renovation, the MTA put several large armchairs in the Dining Concourse. These chairs looked like the fancy chairs from the 20th Century Limited train. They were removed in 2011 to improve how people moved through the concourse.

Since 1999, the terminal's Vanderbilt Hall has hosted the international Tournament of Champions squash championship every year.

Grand Central in the 21st Century

Early 2000s and 2010s

After the September 11 attacks in 2001, security was increased in Grand Central and other transit hubs. The Joint Task Force Empire Shield (National Guard personnel) has been present in the terminal ever since. The MTA also ordered two American flags to be hung in the Main Concourse.

By 2010, the station was getting new flooring, which was finished in 2012. This included 45,000 square feet of marble tile. The matching marble came from the same quarry in Tennessee as the original.

In 2011, a fancy restaurant called Metrazur closed. It was soon replaced by an Apple store.

Centennial and Recent Changes

On February 1, 2013, the terminal celebrated its 100th birthday with a ceremony and many events. The American Society of Civil Engineers recognized the terminal as a Historic Civil Engineering Landmark. Grand Central also became a "sister station" with Tokyo Station in Japan and Hsinchu railway station in Taiwan, both of which also opened in 1913.

The main entrance foyer on 42nd Street was renamed after former U.S. First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis in 2014. Also in 2014, a very tall skyscraper called One Vanderbilt was proposed next to Grand Central. This building, finished in 2020, has a transit hall and underground access to Grand Central. Another project announced in 2019 is to replace the Grand Hyatt New York hotel with a new building.

In December 2017, the MTA approved plans to replace the display boards and public announcement systems in Grand Central. The next-train departure screens will be replaced with new LED signs.

As part of a plan for 2020–2024, the concrete and steel of the Grand Central Terminal train shed will be repaired. This work will involve digging up parts of Park Avenue for several years.

Long Island Rail Road Access

The East Side Access project, which started in 2007, will bring Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) trains to a new station underneath Grand Central Terminal. LIRR trains will arrive and depart from a two-level, eight-track tunnel. This tunnel will be more than 140 feet below Park Avenue and over 90 feet below the Metro-North tracks. It will take about 10 minutes to reach the street from the lowest level, which is more than 175 feet deep. A new 350,000-square-foot area for shops and restaurants will be built.

The idea for LIRR trains to come to the east side of Manhattan dates back to 1963. In 1977, the MTA decided to use Grand Central as the terminal for the LIRR route. However, due to money problems in New York City, the project was delayed.

The East Side Access project was restarted in the 1990s. This was because a study showed that more than half of LIRR riders worked closer to Grand Central than to their current station, Penn Station. The new stations and tunnels are expected to begin service in December 2022.

MTA Buys Grand Central

In December 2006, an investment group bought the station. The lease with the MTA was changed to last until February 28, 2274. The MTA paid $2.4 million in rent each year.

In November 2018, the MTA suggested buying the Hudson and Harlem Lines, as well as Grand Central Terminal, for up to $35.065 million. The MTA wanted to buy these assets to avoid future double-payments on its leases. The MTA's board approved the purchase. The deal was finalized on February 28, 2020. The MTA now owns the terminal and the rail lines.

Recent Events

In 2017 and 2018, the terminal planned to replace some of its food places with more upscale restaurants. MTA officials wanted trendier businesses, even if it meant lower rents.

In 2020, one restaurant refused to pay rent, complaining about more homeless people using the dining concourse. The MTA threatened to evict the restaurant as the COVID-19 pandemic began. Another tenant, the Campbell, also had issues with rent during the pandemic. As the pandemic caused lockdowns, fewer people used the terminal. The New York Times reported that Grand Central was nearly empty.

Events and Exhibitions

Grand Central Terminal has hosted many special events and exhibits over the years:

- In 1916, plans for improvements to Riverside Park were shown.

- In 1918, a food conservation exhibit was held.

- In December 1931, a model of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine was displayed.

- In October 1934, photos of Depression-era improvement projects were shown.

- From 1935 to 1936, an exhibit of New York state tourist attractions was held.

- The Kodak Photographic Information Center was on the east balcony through the 1950s and 1960s.

- In 1955, a model of the aircraft carrier USS Shangri-La was displayed.

- In May 1958, a model of the Sergeant missile was shown.

- In 1988, a Double Dutch jump-roping competition was held in the Main Concourse.

Images for kids

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |