HM Land Registry facts for kids

| Welsh: Cofrestrfa Dir Ei Mawrhydi | |

|

|

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1861 |

| Type | non-ministerial government department |

| Jurisdiction | England and Wales |

| Employees | 6,393 (as at 2021[update]) |

| Agency executive |

|

His Majesty's Land Registry is a special part of the UK government. It was started in 1862. Its main job is to keep a record of who owns land and buildings in England and Wales.

The Land Registry works closely with the government. However, it runs its daily operations independently. It charges fees for its services, and these fees go to the government's treasury. The current head of the Land Registry is Simon Hayes.

Other parts of the UK have similar offices. Registers of Scotland does this job in Scotland. Land and Property Services handles records for Northern Ireland.

Contents

What the Land Registry Does

The Land Registry records who owns property. It also notes other important details about registered land. It is one of the biggest property databases in Europe.

The Land Registry makes sure that the ownership of land is clear and guaranteed. It records ownership for properties that are owned outright (called freehold). It also records properties that are leased for more than seven years (called leasehold).

When we talk about "land," it can mean more than just the ground. It includes buildings on the land. It can even include parts of buildings, like flats, if they are owned separately. Sometimes, the ownership of mines, minerals underground, or even the airspace above a property can be registered.

The Land Registry gets money from the government's treasury. It also charges fees for its services. You can look up information about property ownership and maps online. There is a small fee for some of this information.

If a property is not yet registered, owners can choose to register it. As of March 2024, over 26.7 million properties were registered. This covers about 89% of the land in England and Wales. Registering land helps protect owners from people trying to claim their property. It also makes it easier to sell property because you don't need lots of old paper documents.

Why Land Registration is Important

The Land Registry says that registering land has many benefits:

- It clearly shows who owns a property.

- It creates an easy-to-read document that replaces old paper deeds. This makes buying and selling property simpler and possibly cheaper.

- All property information is kept in the Land Registry's database. This means you don't need to store old, unclear documents. You can quickly and safely view the register online.

- Registering your property with the Land Registry is the best way to protect your ownership. The government backs this registration, giving you strong protection against claims from others.

When land is registered, a "title plan" is made. This plan shows the general shape of the land on a map. The lines on the plan are usually general, not exact. It's still good to keep original property deeds. They can help if there's ever a question about exact boundary lines.

The Land Registry is also helpful for people who invest in property. They can use its online tools to check property prices. The government also uses this data to figure out property values for tax purposes.

Where the Offices Are

HM Land Registry has 14 offices across England and Wales. These are in:

- Birkenhead

- Coventry

- Croydon

- Durham

- Fylde (Warton)

- Gloucester

- Hull

- Leicester

- Nottingham

- Peterborough

- Plymouth

- Swansea

- Telford

- Weymouth

The main office for HM Land Registry is in Croydon. The department that handles IT and land charges is based in Plymouth.

Over the years, some offices have closed or merged to make the service more efficient. For example, the main office moved from Lincoln's Inn Fields in London to Croydon in March 2011.

How the Land Registry is Organized

Each local office has a manager and a senior lawyer. They also have people who manage daily operations and ensure honesty.

In the past, you sent your application to the office that covered your area. Now, most applications can be handled by any Land Registry office. Since January 6, 2014, all paper applications from the public are processed at the Citizen Centre in the Swansea Office.

The Chief Land Registrar is also the Chief Executive. They lead the organization. A board helps set the overall plan for the department. Other senior groups manage the daily work.

Since December 1990, anyone can look at the Land Register. For a fee, you can find out who owns a registered property. You can also get a copy of any registered title. This can be done online.

The Land Registry has won awards for its service. Most customers say their service is good or excellent. If you have a complaint, there is an Independent Complaints Reviewer who can help.

Dealing with Disputes

If there was a disagreement about a Land Registry application, it used to be handled by an independent office called the Adjudicator to HM Land Registry. Since July 2013, these types of disputes are now handled by a special part of the First-tier Tribunal, which is a court.

A Look at History

The idea for a land registration system came about in 1857. The Land Registry Act 1862 officially created the Land Registry. It allowed for the registration of freehold and long leasehold properties.

Brent Spencer Follett was the first Chief Land Registrar. He opened the first office in London on October 15, 1862. He had a small team of six people.

At first, registering property was not required. Also, if a property was registered, later changes in ownership didn't have to be registered. This caused problems. The Land Transfer Act 1875 fixed many of these issues. However, registration still wasn't compulsory.

Later, the Land Transfer Act 1897 made registration compulsory in some areas. London was one of the first places to adopt this. This led to the Land Registry growing. Women started working there, and typewriters were introduced.

New headquarters for the Land Registry were built in London between 1905 and 1913.

Two important laws about land were passed in 1925: the Law of Property Act 1925 and the Land Registration Act 1925. The government thought all of England and Wales would be registered by 1955, but it took much longer. During World War II, the Land Registry had to move its offices to Bournemouth because of air raids.

After the War

In 1950, 88 years after it started, the Land Registry registered its one millionth property. As more people owned homes after the war, the number of properties to register grew a lot. This made the process slower. To help, new offices were opened in places like Tunbridge Wells and Lytham St. Annes. In 1963, the registry reached two million registered properties.

Theodore Ruoff, who became Chief Land Registrar in 1963, explained three key ideas of land registration:

- The mirror principle: The register should show all important facts about a property's ownership clearly and completely.

- The curtain principle: The register should be the only place buyers need to look for information. It should not show private details.

- The insurance principle: If there's a mistake and someone loses money because of it, they should be able to get compensation.

Many new offices opened in the following years across England and Wales.

In the past, land registers were not public. Creating them involved a lot of typing and drawing maps by hand. Copies were also made by hand and sewn into large certificates. These certificates were proof of ownership.

In 1986, the Plymouth Office was the first to start creating registers using computers. This made the process much faster. In 1990, registering property became compulsory across all of England and Wales when a property was sold. That same year, the ten millionth property was registered, and the Land Register became open to the public.

Later, in 1998, new reasons for compulsory registration were added. These included giving land as a gift or using land to get a mortgage. This greatly increased the rate of land registration.

The Land Registration Act 2002 kept most of the system in place. It also allowed for electronic property transfers in the future. Because of this act, paper Land and Charge Certificates are no longer issued.

In 2005, a new, modern office for the Information Systems department opened in Plymouth.

Chief Land Registrars

Here is a list of the people who have led the Land Registry:

- Brent Spencer Follett (1862–1886)

- Robert Hallet Holt (1886–1900)

- Sir Charles Fortescue Brickdale (1900–1923)

- Sir John Stewart Stewart-Wallace (1923–1941)

- Rouxville Mark Lowe (1941–1947)

- Sir George Harold Curtis (1947–1963)

- Theodore Burton Fox Ruoff (1963–1974)

- Robert Burnell Roper (1974–1983)

- Eric John Pryer (1983–1990)

- John Manthorpe (1990–1996)

- Stuart John Hill (1996–1999)

- Peter Collis (1999–2010)

- Marco Pierleoni (2010–2011)

- Malcolm Dawson (2011–2013)

- Ed Lester (2013–2015)

- Graham Farrant (2015–2018)

- Mike Harlow (Acting) (2018–2019)

- Simon Hayes (2019–)

Property Records: Registers and Plans

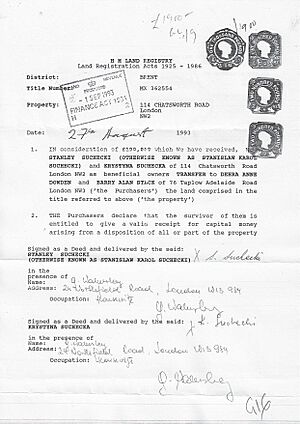

The HM Land Registry keeps two main documents for registered land in England and Wales: the title register and the title plan. These documents give important details about who owns a property, its boundaries, and any special rights or rules that apply to it.

The Title Register

The title register is a detailed record of ownership and legal interests for a specific property. It has three main parts:

- Property Register: This part describes the land, including its address. It also states what kind of ownership it is (like freehold or leasehold). It might also include details about rights to use parts of other land, or rules about light, air, or shared walls.

- Proprietorship Register: This lists the name(s) of the current owner(s). It also shows the type of ownership (like "absolute" or "possessory"). If the property was recently bought, it might show the purchase price.

- Charges Register: This records any burdens on the property. This includes things like mortgages, rules that limit what you can do with the land, or rights that allow others to use parts of the land.

The title register is a legal document used when properties are bought, sold, or when there are disagreements.

The Title Plan

The title plan is a map that shows the general boundaries of the registered land or property. It is based on Ordnance Survey maps. It gives a visual idea of the property, showing:

- Approximate boundary lines, usually marked in red.

- Ways to access the property, nearby land, and neighboring properties.

- Land features or extra areas mentioned in the register, like paths or reserved land.

While the title plan is very useful, it doesn't always show the exact legal boundaries. For very precise boundary questions, other legal documents might be needed.

How to Access Records

Both the title register and title plan can be viewed by the public. You can get them online through the HM Land Registry's services for a small fee. These documents are very important for lawyers, property experts, and anyone who wants to understand property rights or planning rules.

Things to Remember

Even though the land register is very thorough, it has some limits. For example, it won't have information about land that hasn't been registered yet. Also, old maps or descriptions might need extra checking.

The Land Registry's job of keeping accurate and up-to-date title plans and registers helps make property transactions in England and Wales smooth and secure.

Plans for Privatization

In the past, there were discussions about making the Land Registry a private company. In 2014, the government asked for public opinion on creating a company to handle the daily work of land registration. This company could have been fully owned by the government or by private businesses. The idea was that the Chief Land Registrar's office would still be part of the government and would regulate this new company.

Many people, including Land Registry staff and legal experts, were against this idea. They worried about a private company having control over valuable land data. In July 2014, the government decided not to go ahead with these changes.

The idea came up again in 2015 and 2016. However, in the 2016 Autumn Statement, the government announced that HM Land Registry would stay a public organization. The plan is for it to become a more digital and data-focused service while remaining in the public sector. This modernization aims to make the Land Registry even more valuable to the economy without needing a lot of government money.

See Also

- Geospatial Commission

- Rural Land Register

- National Land and Property Gazetteer

- Housing in the United Kingdom

- Torrens system

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |