Haast's eagle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Haast's eagle |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Artist's idea of a Haast's eagle attacking moa. |

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: |

Harpagornis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Harpagornis moorei Haast, 1872

|

|

The Haast's eagle (Harpagornis moorei) was the biggest eagle that ever lived. It was the only eagle in the world to be the top hunter in its ecosystem. This amazing bird lived on the South Island of New Zealand. There were no other big predators there.

Fossils show that Haast's eagles lived in forests and shrublands. They also lived in grasslands near river floodplains.

When people arrived in New Zealand, things changed for the eagle. By the year 1400 AD, much of the forest where it lived was burned down. Also, most of the large, flightless moas that the eagle ate were hunted until they became extinct.

Description

Haast's eagles were among the largest known true raptors. Raptors are birds of prey, like eagles and hawks. In size and weight, the Haast's eagle was even bigger than the largest living vultures.

Female eagles were much larger than males. Most experts think female Haast's eagles weighed about 10 to 15 kilograms (22 to 33 pounds). Males weighed around 9 to 12 kilograms (20 to 26 pounds). Some believe the biggest females could weigh over 16.5 kilograms (36 pounds).

The largest eagles alive today are about 40 percent smaller than Haast's eagles. No living eagle is known to weigh more than 9 kilograms (20 pounds) in the wild.

Haast's eagles had a short wingspan for their size. A full-grown female's wingspan was usually up to 2.6 meters (8.5 feet). Some might have reached 3 meters (9.8 feet). This is similar to some large living eagles today. Examples include the wedge-tailed eagle and golden eagle.

Short wings helped Haast's eagles hunt in the thick scrubland and forests of New Zealand. Some people thought these eagles were becoming flightless. But this is not true. Instead, their wings were very broad. This helped them fly well despite their heavy weight.

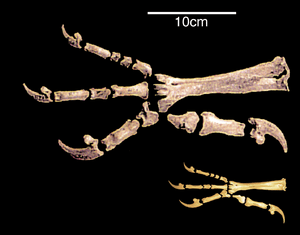

The harpy eagle and the Philippine eagle are very powerful living eagles. They also have shorter wings for living in forests. A lower jawbone from a Haast's eagle was 11.4 centimeters (4.5 inches) long. Its lower leg bone (called the tarsus) was 22.7 to 24.9 centimeters (8.9 to 9.8 inches) long.

For comparison, the largest eagle beaks today are about 7 centimeters (2.8 inches). The longest eagle leg bones are about 14 centimeters (5.5 inches). The Haast's eagle's talons were similar in length to the harpy eagle's. Its front-left talon was 4.9 to 6.15 centimeters (1.9 to 2.4 inches) long. Its back hallux-claw could be up to 11 centimeters (4.3 inches).

The strong legs and huge flight muscles of these eagles were important. They allowed the birds to jump and take off from the ground. This was amazing, given their great weight. Their tail was likely long, over 50 centimeters (20 inches) in females. It was also very broad. This long tail helped them get extra lift when flying. Females could be up to 1.4 meters (4.6 feet) long. They stood about 90 centimeters (3 feet) tall, or even a bit taller.

Behaviour

Haast's eagles hunted large, flightless birds. Their main prey was the moa. A moa could weigh up to 15 times more than the eagle. It is thought that the eagles attacked at speeds up to 80 kilometers per hour (50 miles per hour).

Their size and weight meant they hit with great force. It was like a heavy concrete block falling from an eight-story building. Their large beak could rip into their prey's insides. The prey would then die from blood loss. Since there were no other big predators or scavengers, a Haast's eagle could eat a large kill for several days.

Extinction

Before humans arrived, New Zealand had almost no land mammals. There were only three types of bat. Because there were no land mammals, birds took over all the main roles in the New Zealand animal ecology. Their eggs and chicks were safe from small land animals.

Moa were plant-eaters, like deer or cattle in other places. Haast's eagles were the hunters. They filled the same role as top predators like tigers or lions.

Early human settlers in New Zealand were the Māori people. They arrived around the year 1280. They hunted many large flightless birds, including all moa species. The moa were hunted until they became extinct around 1400. Because its main food source was gone, the Haast's eagle also died out around the same time.

Images for kids

-

Haast's eagle attacking moa by John Megahan

See also

In Spanish: Águila de Haast para niños

In Spanish: Águila de Haast para niños