Hannah Swarton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hannah Swarton

|

|

|---|---|

| Born |

Joana Hibbert or Hibbard

1651 (baptized on 9 March, 1651) |

| Died | 12 October 1708 (aged 56–57) |

| Known for | Captivity by Native Americans and French Canadians |

| Spouse(s) | John Swarton (died 1690) |

| Parent(s) | John and Anne Hibbart |

| Relatives | Children: John, Mary, Samuel, Jasper |

Hannah Swarton (born 1651, died 1708) was a woman from early New England. Her birth name was Joana Hibbert. She became known for being captured by Abenaki Native Americans and held prisoner for about five and a half years. After she was freed, Hannah shared her story with Cotton Mather, a famous writer and minister. He used her experiences to teach moral lessons in his books.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Hannah Hibbard (or Hibbert) was born in Salem, Massachusetts. She was baptized on March 9, 1651.

She married John Swarton in Beverly, Massachusetts, in January 1670 or 1671. They had five children together in Beverly:

- Mary, who died young in 1674

- Samuel, born in 1674

- Mary, born in 1675

- John, born in 1677

- Jasper, born in 1685

In 1687, John Swarton received a land grant in North Yarmouth, Maine. The family moved from Beverly to Casco Bay (in present-day Maine) in 1689.

Captured During War

During a conflict known as King William's War, French and Native American forces attacked English settlements. On May 16, 1690, a large group of French soldiers and Native American warriors attacked the fortified settlement at Casco Bay.

About 75 men in the settlement fought for four days. They surrendered on May 20, expecting to be allowed to go to the nearest English town. However, most of the men, including Hannah's husband John Swarton, were killed. The surviving settlers, including Hannah and her children Samuel, Mary, John, and Jasper, were taken captive.

Life as a Prisoner

Hannah Swarton's story describes the difficulties she faced as a prisoner. She was separated from her children at Norridgewock, Maine. She later learned that her oldest son, Samuel, had been killed. She never saw her son John again after they were separated. She had only occasional contact with her daughter Mary for the first three years.

From May 1690 to February 1691, Hannah traveled many long journeys with her captors through the wilderness of northern Maine. She described being very hungry and forced to work in the snow without enough warm clothes. Hannah's Native American mistress was Catholic. She told Hannah that her captivity was a punishment for not being Catholic.

Hannah believed that her suffering was a punishment for her own mistakes. This was a common idea in the Puritan beliefs of the time. She felt that moving to a rural community without a church was a mistake. Despite her hardships, she believed she would eventually be freed. She hoped to share her story to show God's work.

Time in Quebec

In February 1691, the Native Americans Hannah was with camped near a French family's home in Canada. Hannah was sent to ask them for food. The French family was kind to her. Hannah asked her captor if she could stay the night with the French family, and he agreed.

The French lady of the house helped Hannah. She arranged for Hannah to go to Quebec City, where she could be ransomed (bought back) from her captors. Hannah agreed and was taken to the home of a high-ranking French official. He had her treated at a local hospital. His wife paid the ransom to her Native American master.

Hannah then worked as a housekeeper for the French family. She was fed and clothed well. However, she was pressured to convert to Catholicism. Hannah resisted, using Bible verses to argue with the "Nuns, Priests, and Friars" she met. Eventually, her mistress stopped forcing her to attend church.

While in Quebec, Hannah met other English prisoners. She was later forbidden from seeing them, except for 12-year-old Margaret Gould Stilson.

Return to New England

In November 1695, a man named Matthew Cary went to Quebec. He had permission from the French governor to bring English prisoners back to Boston. In return, nearly a hundred French prisoners held by the English were sent back to Canada.

Hannah Swarton and her son Jasper were on the list of 22 English captives returned from Quebec. Hannah was recorded as being "admitted to our communion" at the First Church in Beverly, Massachusetts, on November 15, 1695.

However, Hannah's daughter Mary Swarton chose to stay in Canada. She had converted to Catholicism and was renamed "Marie Souart." In 1697, she married an Irishman who was also a former captive. Mary became a French citizen and lived the rest of her life in Montreal.

Her Published Story

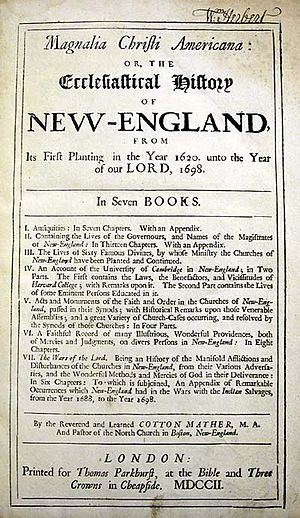

After Hannah and Jasper returned to New England in November 1695, Hannah shared her experiences. Her story was published in 1697 by Cotton Mather. Mather added many religious references to her story, but the main details of her experiences were real.

Cotton Mather used Hannah's story in his sermons and books. He published an expanded version in his famous 1702 book, Magnalia Christi Americana. Mather used Hannah's voice to highlight the importance of staying true to Puritan values and remaining active in the church. He wanted to show the dangers of living in areas without a minister.

Mather showed Hannah as someone who had made mistakes but had found her way back to faith. He used her story to encourage people to think about their own actions. He also used her arguments with the French about religion to teach his audience about the differences between Protestantism and Catholicism. Hannah's resistance to converting showed her strong loyalty to her Puritan faith.

Mather also published Hannah's story alongside that of Hannah Duston. Duston's story became more famous for its theme of revenge against Native Americans. Hannah Swarton's story, however, focused on her endurance in faith and her willingness to learn from her suffering. She did not try to escape but showed strength through her beliefs.

Death

Hannah Swarton died on October 12, 1708, in Beverly, Massachusetts. She was 57 years old.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |