Hao Wang (academic) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hao Wang

|

|

|---|---|

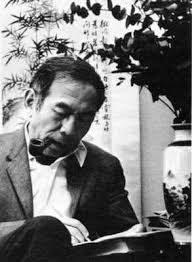

Hao in 1980

|

|

| Born | 20 May 1921 |

| Died | 13 May 1995 (aged 73) New York City, New York, United States

|

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for | Wang tiles Wang B-machine |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral advisor | Willard Van Orman Quine |

| Other academic advisors | Paul Bernays |

| Doctoral students |

|

Hao Wang (born May 20, 1921 – died May 13, 1995) was a brilliant Chinese-American thinker. He was a mathematician, a philosopher, and a logician. A logician is someone who studies how we can reason correctly. He also wrote a lot about the ideas of another famous thinker, Kurt Gödel.

Contents

Hao Wang's Early Life and Education

Hao Wang was born in Jinan, a city in Shandong, China. He went to school in China for his early education. In 1943, he earned a degree in mathematics from the National Southwestern Associated University. After that, in 1945, he got a master's degree in philosophy from Tsinghua University.

His teachers in China included famous philosophers like Feng Youlan and Jin Yuelin. After finishing his studies in China, he moved to the United States. There, he continued to study logic at Harvard University. He earned his Ph.D. in 1948 and started working as a professor at Harvard that same year.

Working and Teaching Around the World

In the early 1950s, Wang studied with Paul Bernays in Switzerland. Later, in 1956, he became a special lecturer at the University of Oxford in England. He taught about the philosophy of mathematics there.

Computers and Logic

Hao Wang was a pioneer in using computers for logic. In 1959, he used an IBM 704 computer to do something amazing. His program proved hundreds of math logic problems in just nine minutes! These problems came from a very important book called Principia Mathematica. This showed how powerful computers could be for solving complex math problems.

In 1961, he returned to Harvard University. He became a professor of mathematical logic and applied mathematics. From 1967 to 1991, he led a research group at Rockefeller University in New York City. This group focused on logic research.

Visiting China

In 1972, Hao Wang was part of a special group of Chinese-American scientists. They were among the first such groups from the U.S. to visit China. This trip helped build connections between scientists from both countries.

Wang Tiles and Computer Science

One of Hao Wang's most important ideas was something called "Wang tiles." Imagine square tiles with colored edges. You can only place them next to each other if their touching edges have the same color.

The Domino Problem

Wang showed that you can use these tiles to represent how a Turing machine works. A Turing machine is a basic model of a computer. The "domino problem" asks if there's a computer program that can tell you if a given set of Wang tiles can cover an entire flat surface without any gaps.

Wang first thought that such a program might not exist. However, in 1966, his student, Robert Berger, found a set of Wang tiles that could only tile the plane in a non-repeating pattern. This was a big discovery in the world of math and computer science. Wang's work also helped shape the field of computational complexity. This field studies how much time and resources computers need to solve problems.

Philosophy and Kurt Gödel

Hao Wang was also a deep thinker about philosophy. He had a special way of understanding the ideas of Ludwig Wittgenstein, another famous philosopher. Wang called his own philosophy "substantial factualism." This idea tried to connect abstract theories with the way we talk and think in everyday life.

Wang spent a lot of time studying and writing about Kurt Gödel's philosophical ideas. Gödel was one of the most important logicians of all time. Wang's books helped many scholars understand Gödel's later thoughts on philosophy.

Awards and Legacy

In 1983, Hao Wang received the first Milestone Prize for Automated theorem proving. This award recognized his pioneering work in using computers to prove mathematical theorems.

Hao Wang passed away on May 13, 1995, just a week before his 74th birthday. He died from lymphoma. He left behind his wife, Hanne Tierney, and his three children. His work continues to influence computer science, mathematics, and philosophy.

Images for kids

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |