Harvard Mark I facts for kids

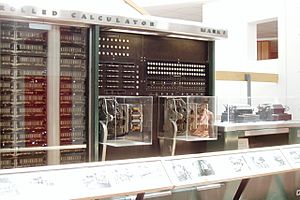

Closeup of input/output and control readers

|

|

| Also known as | IBM Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator (ASCC) |

|---|---|

| Developer | Howard Aiken / IBM |

| Release date | August 7, 1944 |

| Power | 5 horsepower (3.7 kW) |

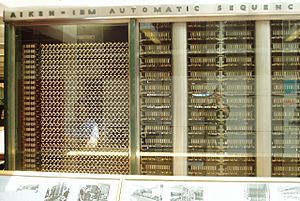

| Dimensions | 816 cubic feet (23 m3) – 51 feet (16 m) in length, 8 feet (2.4 m) in height, and 2 feet (0.61 m) deep |

| Weight | 9,445 pounds (4.7 short tons; 4.3 t) |

| Successor | Harvard Mark II |

The Harvard Mark I, also known as the Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator (ASCC) by IBM, was a very early computer. It was a huge machine that used both electricity and moving parts to do calculations. This computer was very important during the last part of World War II.

One of the first big jobs for the Mark I started in March 1944. A famous scientist named John von Neumann used it to help with the Manhattan Project. He needed to figure out complex math problems for designing the first atomic bomb. The Mark I also created and printed long lists of mathematical tables. This was a goal that the British inventor Charles Babbage had for his "analytical engine" way back in 1837.

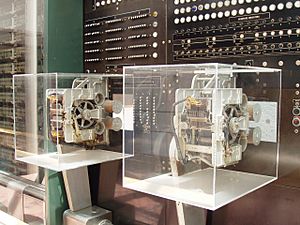

The Mark I was taken apart in 1959. But you can still see parts of it today! Some pieces are on display at the Harvard Science Center in Allston, Massachusetts. Other parts were sent to IBM and the Smithsonian Institution.

Contents

How the Mark I Began

The idea for this amazing computer came from Howard Aiken, a professor at Harvard University. He first showed his idea to IBM in November 1937. After IBM engineers looked into it, the company's chairman, Thomas Watson Sr., personally approved the project in February 1939. He even provided the money to build it.

Howard Aiken had been looking for a company to build his calculator since early 1937. After two companies said no, he saw a demonstration set that Charles Babbage's son had given to Harvard University many years before. This made Aiken study Babbage's work. He added ideas from Babbage's Analytical Engine to his own plan. The Mark I machine "brought Babbage’s principles... almost to full realization," meaning it made many of Babbage's old ideas a reality.

IBM built the ASCC at their factory in Endicott, New York. It was then shipped to Harvard University in February 1944. The computer started doing calculations for the U.S. Navy in May. It was officially given to Harvard University on August 7, 1944.

Building the Giant Machine

The ASCC was made from many different parts like switches, relays, spinning shafts, and clutches. It had 765,000 parts that used electricity and moving pieces. It also had hundreds of miles of wire inside!

The Mark I was truly huge. It took up about 816 cubic feet (23 m3) of space. It was 51 feet (16 m) long, 8 feet (2.4 m) tall, and 2 feet (0.61 m) deep. That's about as long as a school bus! It weighed around 9,445 pounds (4.7 short tons; 4.3 t), which is like the weight of two cars.

All the basic calculating parts had to work together perfectly. They were powered by a 50-foot (15 m) long drive shaft. This shaft was connected to a 5 horsepower (3.7 kW) electric motor. This motor was the main power source and kept all the parts working in sync, like a giant clock.

IBM described the Mark I as the first machine that could do long calculations automatically. It was the biggest electromechanical calculator ever built at that time.

The outside of the Mark I was designed by a famous American designer named Norman Bel Geddes. IBM paid for this design. Professor Aiken was a bit annoyed because he thought the money (about $50,000) should have been used to build more computer parts instead.

How the Mark I Worked

The Mark I had 60 sets of 24 switches. These were used to put numbers into the machine by hand. It could also remember 72 numbers, each with 23 digits.

Here's how fast it was:

- It could do 3 additions or subtractions in one second.

- A multiplication took 6 seconds.

- A division took 15.3 seconds.

- More complex math, like finding a logarithm or a trigonometric function, took over a minute.

The Mark I got its instructions from a long roll of punched paper tape that had 24 channels. It would read one instruction, do it, and then read the next one. There was a separate tape for numbers that it needed to use. The machine kept its instructions and its data (numbers) separate. This way of working is now called the Harvard architecture.

At first, if a program needed to repeat a step or jump to a different part, someone had to do it manually. Later, in 1946, the machine was changed so it could do these jumps automatically. The first people to program the Mark I were Richard Milton Bloch, Robert Campbell, and Grace Hopper. There was also a small team that operated the machine. They were not told what the overall purpose of their work was.

Its Role in the Manhattan Project

Long before the Mark I, in 1928, a scientist named L.J. Comrie used IBM's "punched-card equipment" for science. He used it to calculate tables for astronomy, just like Babbage had imagined. IBM soon started changing its machines to help with these kinds of calculations.

John von Neumann had a team at Los Alamos that used "modified IBM punched-card machines" to figure out how to make an atomic bomb work. In March 1944, he suggested using the Mark I for some of these problems. He arrived with two mathematicians to write a program to study how the first atomic bomb would work.

The Mark I was very precise. It calculated numbers with eighteen decimal places, which was much more accurate than other machines used at the time. This high precision was very important for the complex calculations needed for the atomic bomb.

Aiken and IBM's Relationship

When the Mark I was announced, Professor Aiken put out a press release. He said he was the only "inventor." Only one IBM person, James W. Bryce, was mentioned, even though many IBM engineers helped build the machine. The head of IBM, Thomas J. Watson, was very angry about this. He only went to the dedication ceremony on August 7, 1944, with great reluctance.

Because of this, Aiken decided to build future computers without IBM's help. That's why the ASCC became widely known as the "Harvard Mark I." IBM then went on to build its own computer, the Selective Sequence Electronic Calculator (SSEC). This machine helped IBM test new technology and show off their own computer-building skills.

What Came After the Mark I

The Mark I was followed by several other computers, all built by Howard Aiken:

- The Harvard Mark II (finished around 1947 or 1948) was an improved version of the Mark I. It still used electromechanical relays.

- The Mark III/ADEC (September 1949) started using more electronic components like vacuum tubes. But it still had some mechanical parts, like spinning magnetic drums for storage.

- The Harvard Mark IV (1952) was fully electronic. It replaced all the mechanical parts with magnetic core memory.

The Mark II and Mark III were sent to the US Navy base in Dahlgren, Virginia. The Mark IV was built for the US Air Force, but it stayed at Harvard.

As mentioned, the Mark I was taken apart in 1959. Parts of it are now on display at the Harvard Science Center and were moved to the new Science and Engineering Complex in July 2021. Other parts were given to IBM and the Smithsonian Institution much earlier.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Harvard Mark I para niños

In Spanish: Harvard Mark I para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |