Hemming's Cartulary facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hemming's Cartulary |

|

|---|---|

| Liber Wigorniensis and Hemming's Cartulary proper | |

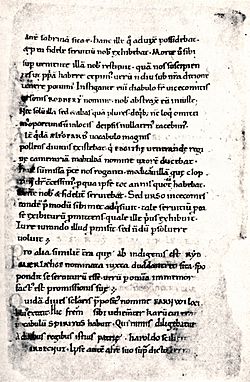

Page from Hemming's Cartulary, folio 121 of the manuscript

|

|

| Author(s) | Hemming (2nd part) |

| Language | medieval Latin, Old English |

| Date | mostly 996 x 1016 (Liber Wigorniensis); late 11th / early 12th century (2nd part) |

| Provenance | Worcester Cathedral |

| Authenticity | contains some spurious charters |

| Manuscript(s) | Cotton Tiberius A xiii |

| First printed edition | 1723 by Thomas Hearne |

| Genre | Cartulary |

| Length | 197 leaves total |

| Subject | Charters of Worcester Cathedral |

| Period covered | 10th and 11th century |

Hemming's Cartulary is a very old book, or manuscript, that holds a collection of important documents. These documents are mostly about land and property owned by the Worcester Cathedral in England. A cartulary is like a medieval filing cabinet, keeping copies of important papers safe.

This special book was put together by a monk named Hemming around the time of the Norman Conquest of England (which happened in 1066). The book you see today is actually two separate collections that were later bound together. It is now kept in the British Library in London.

The first part of the book was made around the late 900s or early 1000s. It's called the Liber Wigorniensis, which means "Book of Worcester". It mainly contains old Anglo-Saxon charters (official documents) and other records about land, often grouped by where the land was located.

The second part was put together by Hemming himself, around the late 1000s or early 1100s. This part, known as Hemming's Cartulary proper, mixes land records with stories. These stories explain how the church of Worcester lost some of its property.

The entire book is the oldest surviving cartulary from medieval England. A big part of its story is about the lands that Worcester Cathedral lost. These lands were taken by powerful people, including kings like Cnut and William the Conqueror. Even local landowners and royal officials took property. The book also tells about the lawsuits the monks tried to win back their lost lands. The two parts of the cartulary were first printed in 1723. The original manuscript was slightly damaged by a fire in 1733, but it was later repaired.

Contents

Who Wrote and Put the Book Together?

Even though the monk Hemming is often given credit for the whole book, it actually contains two different works. Only one of these was truly put together by Hemming. These two works were later bound into one manuscript, which is now called Cotton Tiberius A xiii. It's kept in the Cotton library, which is part of the British Library.

Together, these two works form the very first surviving cartulary from medieval England. The first part is the Liber Wigorniensis, or Book of Worcester. It covers pages (called folios) 1 to 118 of the manuscript. Hemming's own work makes up folios 119 to 142, 144 to 152, and 154 to 200.

How the Manuscript Looks Today

The original book was slightly damaged in a fire in 1733. Luckily, the damage wasn't too bad. The edges of the pages got burned, so a few words along the margins were lost. Because of the fire, the book was rebound in the 1800s. Each page was carefully mounted on its own.

Besides the two main sections, there are three smaller pieces of parchment (animal skin used for writing) bound into the book. These are folios 110, 143, and 153.

- Folio 110 is small, about 70 millimetres (2.8 in) high and 90 millimetres (3.5 in) wide. It lists eight names, probably people who witnessed a land agreement.

- Folio 143 is larger, about 130 millimetres (5.1 in) high and 180 millimetres (7.1 in) wide. It lists the names of jurors from the late 1000s.

- Folio 153 is about 58 millimetres (2.3 in) high and 180 millimetres (7.1 in) wide. It describes the boundaries of a manor (a large estate) in Old English, not Latin. It was written in the 1100s.

The Liber Wigorniensis Section

The first part of the book is a collection of older documents from the early 1000s. These documents are mostly arranged by location. There's also a section at the end with land agreements from the late 900s.

A historian named H. P. R. Finberg gave this section the name Liber Wigorniensis in 1961. This helped to tell it apart from the later section that Hemming actually put together. Historians believe this part was created between 996 and 1016.

There are 155 documents, or charters, in the Liber. Ten of these were added later, sometime in the 1000s. Experts who studied the original book found that five main scribes (people who copied documents by hand) worked on this first section. Their handwriting is small and not very rounded, typical of writing in England in the early 1000s. This section has 117 pages, with 26 lines of text on each page. The written area is about 190 millimetres (7.5 in) tall by 100 millimetres (3.9 in) wide. Some blank spaces in the original book were filled in later with notes about the cathedral's properties.

Hemming's Own Cartulary Section

Hemming wrote the second, later part of the book. This section is a collection of lands and rights belonging to the Worcester Cathedral. It also includes stories about the actions of Wulfstan, who was Bishop of Worcester and died in 1095, and Archbishop Ealdred of York.

In this part, there's an introduction called the Enucleatio libelli. Here, Hemming says he was the one who put the work together. He also says that Bishop Wulfstan was the reason he started the project. Another shorter introduction, the Prefatio istius libelli, explains the purpose of the collection.

Historians often think that Wulfstan asked Hemming to create this work. However, it's not clear if it was made before or after Wulfstan died. Some historians believe Hemming's work was a response to problems the church faced after Wulfstan's death. At that time, royal officials were managing the church's lands. Another idea is that the famous Domesday Book from 1086 inspired Hemming's work.

Hemming's section contains over 50 charters. Some of these are copies of documents already found in the Liber Wigorniensis.

This second section is more than just a collection of documents. It includes other important historical information, especially for Hemming's monastery. The documents are connected by a story that explains why and how the cartulary was created. This story is usually called the Codicellus possessionum. This part also includes a Life (a story about a saint's life) of Bishop Wulfstan.

The documents are mostly grouped by location, but some information is grouped by topic. In two sections, called "Indiculum Libertatis" and "Oswald's Indiculum", the book uses not only charters but also regional information from other sources. These sources recorded the landholdings of important tenants. This information likely came from records gathered for the Domesday survey, which was ordered by William the Conqueror in 1085. These same records were later used to create the Domesday Book.

Some of the documents are in Latin, while others are in Old English. Experts have found that three scribes created this second part of the manuscript. Their handwriting is described as "round and fairly large", showing a style from the late 1000s and early 1100s. This section has 80 pages. Most pages have 28 lines of writing, and the written area is about 190 millimetres (7.5 in) high by 108 millimetres (4.3 in) wide. Some blank areas were filled in later with notes, from landholdings to the dissolution of Worcester Priory in the 1500s.

What the Book is About

Both the Liber Wigorniensis and Hemming's work contain some documents that are not real, or "forged" charters. A historian named Julia Barrow found that at least 25 of the 155 charters in the Liber are forgeries. She also identified over 30 forged charters in Hemming's work, including some that are duplicates from the Liber. Some of Hemming's stories don't always match other historical sources.

Contents of the Liber Wigorniensis

The main goal of the Liber was to record the landholdings of the church and bishop. It also kept a register of the written charters and agreements related to Worcester's property. Because there's no story connecting the documents, the Liber was likely a working document. It was made for the bishop and monks to use, more as a legal tool than a literary work. The Liber was updated over time, which further shows it was a practical document.

The charters in the Liber are very useful for studying people and families (called prosopography) and how land was owned in Anglo-Saxon England. They also show the social connections that people made with their neighbors. In the 900s, the Bishop of Worcester would lease out small estates to important men and women, usually for three lifetimes. This created a network of high-status neighbors connected to Worcester and the bishop's home. These lessees might have gathered at the bishop's residence for social events. Some of these important people, called thegns, even served in the royal army (the fyrd) under the bishop's command. This suggests the bishop had his own group of fighters, possibly to protect his lands.

Hemming's Work

Why it was Created

Hemming's introduction to his work (the Prefatio) says it was made to teach future leaders of the church. It was meant to show them:

- What lands truly belonged to the church.

- Which lands were unfairly taken by bad people.

- How lands were lost during the Danish invasions.

- How lands were lost by unfair royal officials and tax collectors.

- How lands were lost by the violence of the Normans, who took property by force and trickery, leaving hardly anything safe.

Some historians, like Richard Southern, argue that the book wasn't made to be used in lawsuits. Instead, he thinks it was a kind of ideal picture of what the church once had. The goal was to remember what was lost and could not be recovered. Because it tells a story, it's not just a record of landholdings but also a historical work. Unlike the Liber, Hemming's work wasn't updated as property changed hands. This suggests it was more about remembering the past than managing current property.

More recently, historian Francesca Tinti believes Hemming's work served very real needs for the monks at Worcester. The Enucleatio part says Bishop Wulfstan asked for the work to protect the lands meant to feed the monks. This was important because the number of monks grew quickly during Wulfstan's time. When the Norman bishop Samson arrived, the monks had a strong reason to protect their property and rights.

What it Contains

One of the main ideas in Hemming's work is the damage caused to his monastery by royal officials. One famous official from the late 900s and early 1000s was Eadric Streona ("Grasper"). He was a powerful earl who was blamed for taking church land in Gloucestershire and Wiltshire. Hemming might have even invented Eadric's nickname Streona.

Hemming points out that the conquests of England by Cnut and William the Conqueror were especially harmful. He claims the work only covers lands lost that were meant to support the cathedral. However, he describes the loss of several manors (large estates) that the Domesday Book lists as belonging to the bishop. So, the work probably covers more than Hemming says.

It also lists how much money Worcester paid King William to get back things the king had taken. Worcester paid over 45.5 marks of gold (a large amount of money) to get their belongings back. Other people Hemming named as major plunderers of Worcester's lands included Leofric, Earl of Mercia, and his family.

Hemming's work also describes a lawsuit between the Worcester church and Evesham Abbey. This happened between 1078 and 1085. The lawsuit was about lands in Hampton and Bengeworth. The Worcester church said these lands were part of their manors, but Evesham Abbey held them. The dispute was complicated because some land had been given to a relative of an earlier bishop. After the Norman Conquest, these lands went to Urse d'Abetot, the Sheriff of Worcester. Eventually, a settlement was reached in 1086. The lands went to the abbey, but the Worcester church remained the overlord, meaning the abbey owed them military service.

What's Inside the Manuscript?

Here's a quick look at what's in the manuscript, section by section:

| Folios | Section of manuscript | Contents |

|---|---|---|

| 1–21 | Liber Wigorniensis | 28 documents about Worcester, plus other documents |

| 22–27 | Liber Wigorniensis | 8 documents about Winchcombe Shire |

| 28–38 | Liber Wigorniensis | 8 documents about Oxfordshire, plus other documents |

| 39–46 | Liber Wigorniensis | 7 documents about Gloucestershire, plus other documents |

| 47–56 | Liber Wigorniensis | 14 documents, mostly about Gloucestershire |

| 57–102 | Liber Wigorniensis | Land leases (agreements) |

| 103–109 | Liber Wigorniensis | 8 documents about Warndon, plus one other document |

| 110 | Inserted page | List of 8 names |

| 111–113 | Liber Wigorniensis | Land leases |

| 114–118 | Liber Wigorniensis | Various documents, including an Old English sermon, lists of bishops and kings, and land records |

| 119–126 | Hemming's Cartulary | Codicellus possessionum (story of possessions) |

| 127–134 | Hemming's Cartulary | More Codicellus possessionum; Enucleatio libelli (Hemming's preface); "Indiculum libertatis" (later document on the rights of Oswaldslow hundred) |

| 135–142 | Hemming's Cartulary | "Oswald's Indiculum" (on services owed by Oswald of Worcester's tenants); record of an agreement between Wulfstan of Worcester and Abbot Walter of Evesham (added later); part of Domesday Book (added later) |

| 143 | Inserted page | List of jurors from the 1000s |

| 144–152 | Hemming's Cartulary | Charters (official documents) |

| 153 | Inserted page | List of manor boundaries in Old English from the 1100s |

| 154–164 | Hemming's Cartulary | Some charters; Old English boundary descriptions (added later) |

| 165–166 | Miscellaneous | Table of contents from the 1400s for both parts of the book |

| 167–175 | Hemming's Cartulary | List of kings, with royal gifts to the monastery; charters |

| 176 | Hemming's Cartulary | List of Worcester bishops, with their gifts; Prefatio (introduction); list of charters |

| 177 | Inserted page | List of taxes by King William in Old English; list of landholders who paid the geld (a tax) in Worcestershire after Domesday Book |

| 178–200 | Hemming's Cartulary | History of estates recovered by Ealdred and Wulfstan, with charters (some added later); more charters |

History of the Manuscript

The only other cartulary from the 1000s that still exists in England is the Oswald cartulary, which was also put together at Worcester. Some historians think that the way English cartularies were made might have started at Worcester.

We don't know who owned the manuscript after it left Worcester Cathedral Priory, probably when monasteries were closed down in the 1540s. But by 1612, the manuscript was owned by Robert Cotton. There are notes in the manuscript by John Joscelyn, who worked for Matthew Parker, the Elizabethan Archbishop of Canterbury. It's not certain if Parker owned the manuscript.

The manuscript became part of the Cotton library. This library became public property in 1702 after Robert Cotton's grandson died, thanks to an act of Parliament. The manuscript is now part of the British Library's collection.

The manuscript was first published in 1723 as Hemingi chartularium ecclesiæ Wigorniensis. It was edited by Thomas Hearne in two volumes. This was part of a series of historical records published between 1709 and 1735. Hearne printed his edition from a copy made for an antiquarian (someone who studies old things) named Richard Graves. This copy wasn't perfectly accurate; some things were left out, and notes in the margins weren't always copied.

The entire manuscript, Cotton Tiberius A xiii, is listed as number 366 in Helmut Gneuss's book Handlist of Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts.

Images for kids

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |