Hirabayashi v. United States (1987) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hirabayashi v. United States |

|

|---|---|

|

|

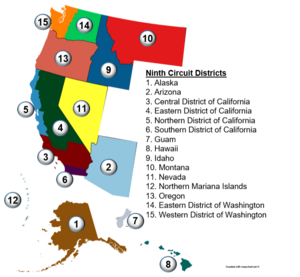

| Court | United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit |

| Full case name | Gordon K. Hirabayashi v. United States of America; United States of America v. Gordon K. Hirabayashi |

| Argued | March 2 1987 |

| Decided | September 24 1987 |

| Citation(s) | 828 F.2d 591 (9th Cir. 1987) |

| Case history | |

| Prior history | No. C83-122V, 627 F. Supp. 1445 (W.D. Wash. 1986) |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting | Alfred Goodwin, Mary M. Schroeder, Joseph Jerome Farris |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Schroeder, joined by Goodwin, Farris |

Hirabayashi v. United States was an important court case. It was decided by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in 1987. This case is famous for two main reasons. First, it cleared the name of Gordon Hirabayashi. He was a Japanese American civil rights leader. His earlier convictions from World War II were removed. Second, it set a rule for when a special court order, called a writ of coram nobis, can be used.

Contents

Gordon Hirabayashi's Story

Gordon Kiyoshi Hirabayashi was born in Seattle, Washington, in 1918. His parents came from Japan. Gordon grew up in America and was an American citizen. He was active in the Boy Scouts and the YMCA. He also participated in his Christian community. Before World War II, Gordon had never been arrested. He had never even visited Japan.

Japanese American Internment

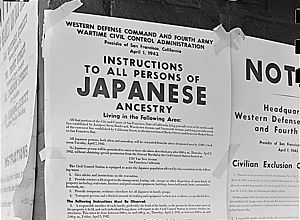

On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Soon after, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared war on Japan. He also issued an order. This order gave the Secretary of War power to limit the freedom of people from Japan living in the U.S.

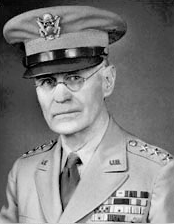

On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt issued another order. It was called Executive Order No. 9066. This order allowed the military to create special "military areas." From these areas, anyone, including American citizens, could be removed. The Secretary of War then gave this power to Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt. He was the commanding general of the Western Defense Command.

General DeWitt then issued many rules. On March 24, 1942, he set a curfew. This rule made all people of Japanese background stay in their homes from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. On May 10, 1942, another order was given. It told all people of Japanese ancestry in Gordon's area to report to a special station. This was the first step before being sent to an internment camp.

Gordon Hirabayashi had learned about his rights as an American citizen. So, he refused to follow these orders. Instead, he went to the F.B.I. office with his lawyer. He told them he would not report to the station. He also said he had not followed the curfew.

Gordon was charged with breaking two rules. One was for not reporting to the station. The other was for breaking the curfew. He spent time in different jails and labor camps.

The case went to court. Gordon's lawyers argued that the orders were unfair. They said the orders went against the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. This amendment protects people's rights. But the judge, Judge Lloyd Llewellyn Black, disagreed. He said the orders were "vitally necessary." He believed Japanese people were masters of "infiltration tactics." In October 1942, a jury found Gordon guilty of both charges. His case then went to the Supreme Court.

Supreme Court's 1943 Decision

In May 1943, the U.S. Supreme Court heard Gordon Hirabayashi's case. They wanted to decide if the curfew orders were fair. They also wanted to know if the orders were based on military needs or racial prejudice.

Gordon's legal team argued that there was no real threat from Japanese Americans. They said the military orders were based on unfair racial ideas. The government, however, argued that in wartime, they didn't have time to figure out who was loyal. They said Japanese culture made it hard to tell. So, they had to remove all people of Japanese ancestry quickly.

On June 21, 1943, the Supreme Court sided with the government. Chief Justice Harlan F. Stone wrote the main opinion. He believed the racial rules were necessary for military reasons. He found no proof that the orders were based on racism. However, Justice William O. Douglas wrote a separate opinion. He said, "guilt is personal under our constitutional system. Detention for reasonable cause is one thing. Detention on account of ancestry is another."

General DeWitt's Secret Report

General DeWitt was the one who issued the curfew and exclusion orders. The government's case in the Supreme Court depended on his orders being for military safety. They said his orders were not based on racism.

In June 1943, General DeWitt released a report. It was called Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast 1942. This report said the orders were needed because of a threat. It also said there was no way to quickly check the loyalty of Japanese Americans. This report supported the government's case. But what Gordon's lawyers didn't know was that there was an earlier version of this report.

Years later, in 1978, a Japanese American woman named Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga found something important. She had been held in an internment camp during the war. While doing research at the National Archives, she saw a copy of DeWitt's report. It looked different from the published one.

She discovered that the first version of DeWitt's report had been changed. Key parts were removed or altered. This was done to make the report match what the government told the Supreme Court. The original report showed the real reason for the orders. DeWitt had written that it was "impossible to establish the identity of the loyal and the disloyal." He also said, "It was not that there was insufficient time... it was simply a matter of facing the realities that a positive determination could not be made."

Other documents also showed DeWitt's true feelings. In a phone call, he said, "There isn't such a thing as a loyal Japanese." He also told a newspaper, "It makes no difference whether the Japanese is theoretically a citizen ... A Jap is a Jap." These statements showed his prejudice.

Fighting for Justice Again

A professor named Peter Irons learned about these hidden documents. He called Gordon Hirabayashi and told him about the new evidence. Gordon said, "I've been waiting for over forty years for this kind of phone call." Irons became Gordon's legal helper. He filed a special request, called a writ of coram nobis, to clear Gordon's old convictions.

The government said they didn't want to defend the old convictions. They knew the orders were unfair. But they didn't want the court to make the new evidence public. They just wanted the charges dropped quietly. However, Judge Donald S. Voorhees disagreed. He held a two-week hearing in 1985.

In 1986, Judge Voorhees made his decision. He found three key things:

- First, the Supreme Court thought DeWitt made a military decision. But DeWitt actually made no such decision.

- Second, the U.S. government changed the documents. They made it look like DeWitt's decision was based on military need, not racism.

- Third, if the Supreme Court had seen the real documents, their decision would likely have been different.

So, Judge Voorhees cleared Gordon's conviction for not reporting to the station. But he did not clear the curfew conviction. He thought the Supreme Court would have seen the curfew and exclusion orders differently. Both Gordon and the government appealed this decision. Gordon wanted the curfew conviction cleared. The government wanted the decision to clear the other conviction reversed.

The Ninth Circuit's Decision

A Historic Ruling

On March 2, 1987, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit heard the case. The judges understood the importance of Gordon's case. They also knew about a similar case involving another Japanese American leader, Fred Korematsu. The court made a strong opening statement:

"The Hirabayashi and Korematsu decisions have never occupied an honored place in our history... These materials document historical judgments that the convictions were unjust. They demonstrate that there could have been no reasonable military assessment of an emergency at the time, that the orders were based upon racial stereotypes, and that the orders caused needless suffering and shame for thousands of American citizens."

The Ninth Circuit agreed with Judge Voorhees. They cleared Gordon's conviction for not reporting to the station. But they disagreed about the curfew conviction. The three judges decided that both of Gordon's convictions should be cleared. This was a big victory for justice.

What is a Writ of Coram Nobis?

The Ninth Circuit's 1987 decision in Hirabayashi v. United States is famous for clearing Gordon Hirabayashi's name. But it's also important for another reason. It set clear rules for when a special court order, called a writ of coram nobis, can be used. This rule applies to all federal courts in the Ninth Circuit.

A writ of coram nobis is a court order. It allows a court to fix an old judgment. This happens when a big mistake is found. This mistake would have changed the original decision. In 1954, the Supreme Court said this writ could be used even if someone had already finished their sentence.

The Ninth Circuit agreed with the lower court's ideas. They said that to get a coram nobis order, a person must show all of these things:

- No other usual way to fix it: If there's another common legal way to challenge a conviction, like an appeal, this writ cannot be used. But if a person is no longer in jail, they might not have other options.

- Good reasons for not acting sooner: The person must explain why they couldn't challenge the conviction earlier. This usually means finding new evidence that wasn't available before.

- Ongoing problems from the conviction: The person must show that the old conviction is still causing them problems. For example, it might affect their job or reputation. The court usually assumes that any criminal conviction causes problems.

- A very serious mistake: The mistake that needs fixing must be a "fundamental error." This means it was a huge error that made the original trial or conviction completely unfair or wrong.