Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | August 5, 1925 |

| Died | July 18, 2018 (aged 92) |

| Occupation | Political activist |

Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga (born August 5, 1925 – died July 18, 2018) was a Japanese American activist. She played a very important role in helping Japanese Americans get justice. This was for the unfair way they were treated during World War II.

Aiko was the main researcher for a special group called the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC). This group was set up by the U.S. Congress in 1980. Their job was to study why and how Japanese Americans were put into special camps during the war.

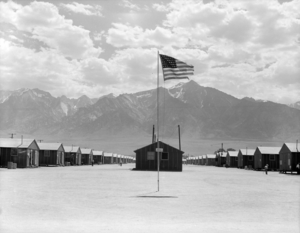

When Aiko was young, she was forced to live in these camps. She was held at Manzanar, Jerome, and Rohwer camps. Later, she found government papers that proved the government's reasons for the camps were not true. These papers showed there was no "military necessity" for holding Japanese Americans.

Her research helped the CWRIC write a report called Personal Justice Denied. This report led to a formal apology from the U.S. government. It also led to payments for those who had been held in the camps. Aiko's work also helped overturn unfair court decisions against Japanese Americans like Gordon Hirabayashi, Fred Korematsu, and Minoru Yasui.

Early Life

Aiko Abe Louise Yoshinaga was born in Sacramento, California in 1924. She was the fifth of six children. Her parents, Sanji Yoshinaga and Shigeru Kinuwaki, had moved from Kumamoto Prefecture in Japan. In 1933, Aiko's family moved to Los Angeles. Her father worked there as a hotel manager.

Life in the Camps

Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga was a high school student in Los Angeles when a big change happened. President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. This order allowed military leaders to remove people from certain areas. This led to over 110,000 Japanese Americans being forced from their homes. They were sent to special camps on the West Coast. The government said this was needed for national security during World War II.

Aiko was an honors student and planned to go to secretarial school. She was just two months from graduating when she had to leave school. She was sent to the camps before she could get her diploma. She remembered her principal telling her and other Japanese American students, "You don't deserve to get your high school diplomas because your people bombed Pearl Harbor." This shows the unfairness they faced.

Aiko was sent to Manzanar, California. She went with her high school sweetheart, whom she had just married. They got married quickly so they would not be sent to different camps. Her parents and siblings were sent to Jerome, Arkansas. Aiko had her first child while in Manzanar. Later, she moved to Jerome, Arkansas, to visit her father before he passed away. Aiko later separated from her husband after he joined the military. Before the war ended, she also spent time in the Rohwer War Relocation Center.

After the war, Aiko received $25. She left the camps and moved to New York City with her mother and four siblings. She found a job as a clerical worker to support her family.

Becoming an Activist

In the 1960s, Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga became involved in civil rights. She joined a group called Asian Americans for Action. This group protested the Vietnam War and nuclear weapons. She also worked for Jazzmobile, a group that taught about jazz music in Harlem. This work helped her understand more about race and racism in the United States. In 1978, she married John "Jack" Herzig and moved to Washington, D.C.. Jack had fought against the Japanese in World War II. He knew little about the Japanese American camps until he met Aiko.

Aiko's friend, author Michi Weglyn, encouraged her to look into government records. These records about the Japanese American camps had just become public. Aiko spent many hours, sometimes fifty or sixty hours a week, at the National Archives. She found and organized thousands of important documents over several years. She brought her own copy machine and kept a detailed system for her files.

In 1980, Aiko joined the National Council for Japanese American Redress (NCJAR). This group was working to get payments from the government for the injustices. The same year, the CWRIC was created. In 1981, the CWRIC hired Aiko as their lead researcher. Soon after, she made a very important discovery.

She found a rare copy of an early report by Lieut. Gen. John L. De Witt. He was the general who oversaw the removal of Japanese Americans. This early report clearly stated that intelligence sources in 1943 believed Japanese Americans were not a threat to U.S. security. The military had claimed there was no time to check each person's loyalty. But DeWitt's early draft said time didn't matter to his plan. He said it was "impossible" to tell Japanese Americans apart, saying "it was impossible to separate the sheep from the goats."

Aiko shared this important document with the CWRIC and other activists. This document was a big part of the CWRIC's report, Personal Justice Denied. The report concluded that the imprisonment of Japanese Americans happened because of "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership." Thanks to Aiko's discovery, the unfair convictions of Gordon Hirabayashi, Fred Korematsu, and Minoru Yasui were overturned. Also, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 was passed. This law gave an official apology and $20,000 to each person who survived the camps.

Aiko and her husband Jack later worked for the Department of Justice. They helped identify Japanese Americans who could receive these payments.

Later Life

In 1989, Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga finally received her high school diploma from Los Angeles High School. She got it along with some of her former classmates. The diploma was dated June 26, 1942.

Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga's husband, Jack Herzig, passed away in 2005.

In 2009, Aiko published a dictionary of terms about the camps. She encouraged people to use accurate words, like "concentration camps" instead of "internment camps." This was because "internment" often suggests something that is militarily justified.

In 2011, she received the Spirit of Los Angeles award for her work.

In 2016, a documentary film was made about Aiko. It was called Rebel with a Cause and was directed by Janice D. Tanaka.

Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga passed away in 2018 in Torrance, California. She was 92 years old.

See also

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |