History of African Americans in Omaha in the 19th century facts for kids

The history of African Americans in Omaha in the 19th Century tells the story of black people who lived in Omaha, Nebraska, during the 1800s. Their journey began even before Omaha was a city, with individuals like York, an enslaved man who traveled with the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1804. African Americans have been part of the Omaha area since at least 1819, when fur traders lived there.

After the American Civil War (1861-1865), many black people moved to Omaha. They worked together to create strong communities, forming many black churches and social and political groups. For example, Father John Albert Williams arrived in Omaha in 1891 and became a very important religious leader. Omaha also had Nebraska's first two black school teachers, Lucy Gamble and Eula Overall.

Towards the end of the century, three black newspapers started in the city. These were founded by George F. Franklin, Thomas P. Mahammitt, and Ferdinand L. Barnett. Many people from Omaha helped start the National Afro-American League in 1890. African Americans also played a big part in the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition, a large fair held in Omaha.

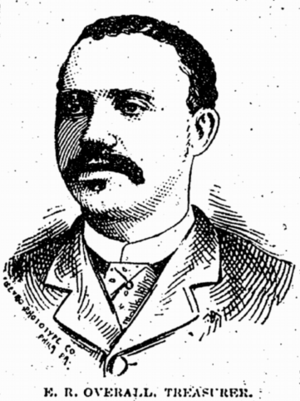

The city was home to some of Nebraska's most active African American politicians. The first black candidate for the state legislature ran in 1880. In 1890, Edwin R. Overall was chosen by a political party to run for the legislature. Nebraska's first black state legislator, Matthew Ricketts, was finally elected in 1892.

Before gathering mostly in North Omaha, African American residents lived in different parts of the city. In the 1860s, the U.S. Census showed 81 "Negroes" in Nebraska, with ten of them being enslaved. By 1880, there were almost 800 black residents, many of whom were brought in by the Union Pacific Railroad during worker strikes. By 1884, three black churches had been founded. By 1900, the number of black residents grew to 3,443, out of a total city population of 102,555.

Contents

Early Days in Omaha

The first time a black person was recorded in the Omaha area was in 1804. This was "York", an enslaved man who belonged to William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. More black people, likely enslaved, were noted in the area that is now North Omaha in September 1819. This was when Major Stephen Harriman Long's expedition arrived at Fort Lisa. They reportedly lived at the fort and on nearby farms.

After a brief period of slavery in Nebraska, the first free black person to live in Omaha was Sally Bayne, who moved there in 1854. An early idea for the Nebraska State Constitution in 1854 said that only "free white males" could vote. This rule actually stopped Nebraska from becoming a state for almost a year. In the 1860s, the United States Census showed 81 "Negroes" in Nebraska, with ten of them being enslaved. Most of these people lived in Omaha and Nebraska City.

Some of the very first African American residents in Omaha might have arrived through the Underground Railroad. This was a secret network that helped enslaved people escape to freedom. One path led through a small log cabin near Nebraska City, built by Allen Mayhew in 1855. Today, this cabin is honored as the Mayhew Cabin Museum. One story tells of Henry Daniel Smith, born in Maryland in 1835, who was an escaped enslaved person. He came to Nebraska using the Underground Railroad and was still living in Omaha in 1913, working as a broom-maker.

Building a Community

By 1867, enough black people had gathered in Omaha to form a community. They founded St. John's African Methodist Episcopal Church in the Near North Side neighborhood. This was the very first church for African Americans in Nebraska. The first recorded birth of an African American in Omaha happened in 1872, when William Leper was born.

Another church, St. Philip's, began as a chapel of the old Trinity Cathedral in 1882. In 1891, Father John Albert Williams came to Omaha to lead the St. Philip's church community.

George T. McPherson was known as Omaha's first important black musician. He arrived in Omaha in the early 1870s and opened a music studio. Thomas P. Mahammitt's newspaper, Enterprise, called McPherson "the leading pianist of the [African-American] race."

In 1879, John Lewis started a brass band with eleven members. Professor Toozer, a former drummer in the British Army Band, taught them. The band was called "Lewis' Excelsior Brass Band." John Lewis was the president, Cyrus D. Bell was the secretary, and D. H. Johnson was the treasurer. This band played at many events, including a celebration in 1880 for the 15th Amendment, which gave black men the right to vote. They also played on August 4, 1887, to celebrate Emancipation Day.

Getting Involved in Politics

Black men and women quickly formed groups to work on political, social, and community issues. In June 1870, Richard D. Curry was chosen as the Republican candidate for Trustee or Alderman in Omaha's Third Ward. However, white Republicans in Omaha did not support Curry and chose someone else. This made many black people in Omaha distrust the Republican Party. A group of black citizens, led by John Lewis, was formed. They encouraged black people to vote independently and not always support one political party. This was a direct response to the Republican Party rejecting Curry.

In January 1876, Edwin R. Overall, William R. Gamble, and Rev. W. H. Wilson organized a State Convention of Colored Men. The convention met to talk about serious issues and to choose representatives for a national meeting later that year. Overall, Dr. W. H. C. Stephenson, Wilson, and Gamble were chosen as representatives. Wilson led the meeting, and Cyrus D. Bell was the secretary.

Cyrus D. Bell, who had been enslaved, was suggested for city, county, or state office by the Anti-Republican Omaha Herald newspaper in 1878. The newspaper pointed out that the Republican Party often prevented black men from holding office, even though black voters strongly supported them. Throughout his life, Bell often expressed his frustration that the Republican Party in Nebraska did not do enough to help black candidates get elected or appointed to positions.

In the late 1860s, Edwin R. Overall moved to Omaha from Chicago. Overall had been working to improve life for black people even before the Civil War. He and Bell were often chosen to represent the black community in Omaha. At a celebration in 1879 for the 15th Amendment, Overall and Bell both spoke. Overall talked about how former Confederate leaders were getting elected to federal offices. Bell, as usual, focused on the need for black people to vote independently and that freedom alone did not make them full citizens. Other important leaders in the community included Emanuel S. Clenlans, H. W. Coesley, and Gabriel Young.

In the 1870s, Omaha became a popular place for black people moving from other areas. This movement of black people to Nebraska and Kansas was a big public topic in 1879 when a large group of migrants arrived in the city.

Organizing for Change

Even with some disagreements, black Republicans in Omaha became very organized by 1880. In August of that year, a group of black people from Omaha attended the state Republican convention. Also that month, a "State Convention of Colored Americans" met. This was part of the Colored Conventions Movement and was led by Overall, Dr. W. H. C. Stephenson, and others. Overall was suggested by the group as a candidate for the state legislature. However, Overall and Stephenson both tried to get the nomination, which divided the community, and the Republican Party did not choose either of them.

Overall's daughters later became teachers. Eula Overall taught in Omaha from 1898 to 1903. In 1880, one of his daughters was not confirmed for a teaching position. In 1882, Stephenson was supported by a group of black people in Omaha to be a Republican candidate for the legislature. Overall and C. C. Cary created a group called the Workingmen's Central Committee, which supported Overall for this nomination. Cyrus D. Bell felt this was unfair and protested that Overall was getting his nomination through improper ways. Overall was chosen at the first State Convention of black people ever held in Nebraska to be a representative to the National Convention of Colored Men in Nashville.

In the 1880s, Overall became active in workers' rights. He joined the Knights of Labor and led black worker groups in the city. In 1890, Overall finally received the Republican nomination for the state legislature and was also supported by the labor party. However, he lost the election. Local black newspapers believed that if white Republicans in his district had voted for him, he would have won. They thought his loss was due to racist voting by Omaha Republicans. In 1893, Overall ran for a position on the Omaha City Council as a Populist candidate, supporting workers' rights.

Black Newspapers in Omaha

The black community in Omaha started several newspapers. The first was The Progress, founded in 1889 by Ferdinand L. Barnett with help from his brother, Alfred S. Barnett. Cyrus D. Bell started the Afro-American Sentinel in 1892. In 1893, George F. Franklin began publishing the Enterprise, which was later published by Thomas P. Mahammitt. The Enterprise lasted longer than any other early African American newspaper in Omaha.

The Sentinel was known for supporting the Democratic Party, unlike the Republican-leaning Progress and Enterprise. The three newspapers became rivals. For example, in 1895, after Booker T. Washington's Atlanta Compromise Speech, they had different views. Barnett's Progress was against any compromise. Franklin's Enterprise supported Washington's idea of compromise. Bell's Sentinel strongly agreed with Washington's position.

The Afro-American League

In late 1889 and early 1890, Timothy Thomas Fortune from Chicago called for local groups to be formed to help black people advance. These local groups would then meet in January 1890 to create the National Afro-American League. On January 9, 1890, a meeting was held in Omaha for this purpose. Overall was chosen to lead the meeting.

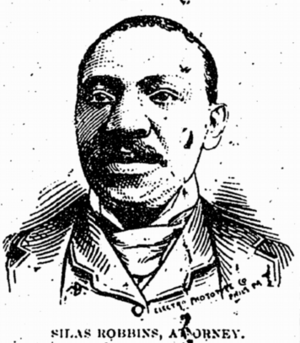

There was some disagreement about the local league's rules. While some supported Overall, Matthew Ricketts, Walker, and Bell strongly opposed Overall's control over writing the rules. Ricketts initially thought white people should not be allowed in the league, fearing they would take over. However, Walker convinced others that white people should be included. There was also a discussion about membership fees. Ricketts, A. S. Barnett, and Thomas were chosen to represent the local league at the national convention. Silas Robbins also attended the national convention as a representative from the Republican Colored Club.

At the national meeting, Ricketts gave a famous speech. He talked about how black voters had been used by political parties who did not help them once they were in power. He urged black people to support the "Afro-American party" instead of existing political parties.

On April 30, 1890, Omaha leaders called for a meeting of black Nebraskans. They wanted to discuss equal rights, form a permanent state league, and help black people who wanted to move to Nebraska to buy homes and farms. The meeting was called by A. S. Barnett, M. O. Ricketts, G. F. Franklin, and others. Topics discussed at this State Afro-American League meeting included segregated restaurants, barbershops, and public places. They spoke out against unfair treatment in both the South and the North. A key point of disagreement at the meeting was a call by Cyrus Bell and Matthew Ricketts for black people to stop giving their full support to Republicans and instead vote based on their own beliefs. This idea was not popular with delegates who did not live in Omaha.

Achievements and Challenges

Violence against black people was a major concern in the community. It was often discussed at meetings and in churches. In 1878, a serious incident occurred in Nebraska City. Two black men, Henry Jackson and Henry Martin, were accused of a crime and sentenced to prison. However, they were attacked by a mob in Nebraska City in December 1878. In 1891, a man named George Smith was attacked in Omaha. In 1894, Sam Payne was also threatened with violence. Local leaders like James Alexander, Ricketts, Richard Gamble, and Bell spoke out strongly against these acts in Omaha, and Payne's safety was ensured.

On September 20, 1894, Ida B. Wells, a famous anti-violence activist, came to Omaha to speak and help start a local anti-violence group. In December 1894, the Anti-Violence League was founded with John Albert Williams as president. In this role, Williams often tried to calm Omaha's black community during times of racial tension.

In 1892, Dr. Matthew Ricketts became the first black person elected to serve in the Nebraska Legislature, serving two terms. In 1895, Silas Robbins was the first black lawyer allowed to practice law in Nebraska.

Another disagreement in the community happened in 1895. G. F. Franklin was appointed Inspector of Weights and Measures with the support of Thomas and Ella Mahammitt, but against Bell's protest. This was partly due to a money dispute in a social club that Franklin and Bell both belonged to.

Later in 1895, Ella Mahammitt (wife of Thomas P. Mahammitt) traveled to The First National Conference of the Colored Women of America. This meeting was held in Boston, Massachusetts, in July 1895. The main goal of the convention was to discuss the education of black children. The group named themselves the National Federation of Afro-American Women. Ella Mahammitt was elected as Vice-President representing the West at the meeting. She worked closely with Margaret James Murray, who was the wife of Booker T. Washington. In 1896, she was on a committee for the next organization, the National Association of Colored Women, led by Mary Church Terrell. Other important African American women leaders in Omaha included Ophelia Clenlans, Nettie Johnson, Laura Craig, Clara Franklin, Lucy Gamble, and Comfort Baker. These women, along with Mahammitt, were officers of Mahammitt's Omaha Colored Women's Club in 1896. All seven women contributed to a special Easter edition of The Enterprise in 1896, which was entirely produced by women.

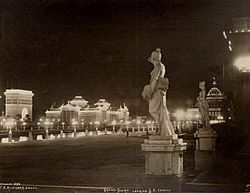

Trans-Mississippi Exhibition

In the late 1890s, black people in Omaha wanted to use two big events to highlight the contributions of African Americans in Nebraska. These events were the 1897 Tennessee Centennial and International Exposition in Nashville and the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition in Omaha. Leaders like J. C. C. Owens, M. O. Ricketts, T. P. Mahammitt, and Franklin played key roles in organizing these efforts. They successfully sent a group to the Tennessee exhibition and made sure African Americans had a central presence at the Omaha exhibition.

Edwin R. Overall, John Albert Williams, and Cyrus D. Bell worked to bring a convention of the National Colored Personal Liberty League to Omaha in August 1898 during the Trans-Mississippi Exposition. There was also a "Congress of Representatives of White and Colored Americans" and meetings of the National Colored Press Association and the Western Negro Press Association. At the Western Negro Press Association meeting, John Albert Williams was chosen as first vice president and Bell as treasurer.

However, relationships between political allies like G. F. Franklin, F. L. Barnett, M. F. Singleton, and M. O. Ricketts became strained before the exhibitions. This was because black people were not included enough in the city's organizing groups. In The Progress, Barnett felt that Singleton and Franklin's support for the exhibitions was not genuine. He pointed out that Franklin was slow to pay for his share of the exhibition and did not push enough for black people to be hired for jobs related to the exhibition. Franklin argued back that Matthew Ricketts, who was a member of the state house of representatives, was not doing enough to push for black employment in government jobs. In The Sentinel, Cyrus D. Bell, a leading black Democrat in Omaha, believed that Ricketts' desire for power was the main problem and also criticized Franklin.

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |